Explore This Issue

June 2012Presentation: A 38-year-old woman presented with a chief complaint of throat pain of four weeks duration and hoarseness of several years duration. She eventually presented to the otolaryngology clinic complaining of a four-week history of odynophagia associated with a frequent urge to clear her throat. She had had a 35-pound weight loss over the previous 10 weeks, after the birth of triplets. She denied any fever, chills or shortness of breath. Another otolaryngologist had previously evaluated her and noted a lesion on her vocal fold. The patient had been treated with a trial of oral corticosteroids, which did not improve her symptoms. Her past medical history was otherwise notable for gastroesophageal reflux and the Caesarean section delivery of triplets. Her medications included acyclovir, omeprazole, aluminum hydroxide/magnesium hydroxide/simethicone and naproxen. She denied any tobacco or alcohol use and had not traveled outside the U.S. Videostroboscopy was notable for a left vocal fold papillomatous polyp near the anterior commissure, as well as diffuse nodular-appearing edema of the supraglottis and posterior commissure (Figure 1).

—Submitted by Jonathan B. Salinas, MD; Soroush Zaghi, MD; Gerald S. Berke, MD and Jennifer L. Long, MD, PhD, department of head and neck surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles.

What’s your diagnosis? How would you manage this patient? Go to the next page for discussion of this case.

Management:

The patient was scheduled for microsuspension direct laryngoscopy and excisional biopsy of the vocal fold lesion in the operating room. In the meantime, she began treatment for laryngopharyngeal reflux with diet modification and twice daily proton-pump inhibitor medication. A pre-operative chest X-ray was normal. A direct laryngoscopy was notable for extensive papillomatous-like lesions involving the false vocal folds and ventricle and extending superiorly to the aryepiglottic fold. The true vocal folds contained fewer lesions than the supraglottis. These lesions were debrided using cold steel instruments and sent as a biopsy specimen for permanent section. Complete excision was not feasible given the extensive disease. CO2 laser microsurgery was also deferred pending pathologic diagnosis given the unusual presentation.

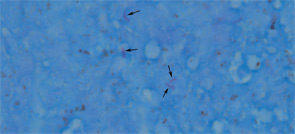

Histopathology revealed multiple squamous papillomas with surface ulceration, fibrinopurulent exudate and marked underlying chronic granulomatous inflammation. An AFB stain demonstrated scattered acid-fast bacilli (Figure 2). The biopsy specimen was negative for human papillomavirus (HPV). The patient was diagnosed with laryngeal tuberculosis and was referred to an infectious disease specialist for further management, which included RIPE [rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol] therapy. On follow-up evaluation two months after beginning therapy, the patient presented with significant improvement and near-complete resolution of her laryngeal symptoms and signs.

Discussion:

Tuberculosis is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Although there are highly efficacious treatment options against tuberculosis, it continues to be a major global health problem. In 2010, the World Health Organization reported an estimated 8.5 to 9.2 million cases and 1.2 to 1.5 million deaths, including deaths from tuberculosis among HIV-positive individuals.1 Recent studies have linked the development of tuberculosis with the following risk factors: malnutrition, failure to receive treatment for latent tuberculosis infection or a treatment duration of fewer than six months, age 0–10 years, living in a household with a person with tuberculosis, smoking, diabetes, having a tuberculin skin test that is larger than 5 mm and using TNF-α drugs and new immunosuppressive treatments.2,3 Although the pulmonary system is most commonly affected, extrapulmonary involvement occurs in sites that include the lymphatics, pleura, bone, genitourinary system, meninges, peritoneum and larynx.4,5

There are two theories on the etiology of laryngeal tuberculosis: bronchogenic and hematogeneous. The bronchogenic theory states that the larynx is infected by direct spread from the endotracheal tree. It is believed that this mechanism accounts for most cases of laryngeal tuberculosis.6 The hematogeneous theory proposes that the larynx is infected via bloodborne spread from non-pulmonary sites, which explains the rare occurrence of a normal chest X-ray, as in this case.6 Before the development of anti-tuberculosis chemotherapeutics, the incidence of laryngeal tuberculosis in cases of pulmonary tuberculosis was described as 37.5 percent by Auerbach and 48 percent by Harbersohn.7,8 Once tuberculosis therapy became available, laryngeal tuberculosis became quite rare, occurring in fewer than 1 percent of tuberculosis cases.9 For this reason, tuberculosis may be overlooked in the differential diagnosis of laryngeal disease.4

The clinical presentation of laryngeal tuberculosis has evolved over the past 100 years. In the past, patients usually presented with advanced pulmonary disease with a productive cough and significant constitutional symptoms, which included weight loss, malaise and night sweats. The most common laryngeal symptom was hoarseness, likely accompanied by severe pain and dysphagia. A recent series of tuberculosis patients with laryngeal involvement showed that they seldom suffer from systemic symptoms. Interestingly, the series by Hunter and colleagues reported that only about half of patients presented with cough.10 Nevertheless, hoarseness continues to be the most common complaint.4

The laryngoscopic findings of tuberculosis are diverse. Auerbach and colleagues described multiple areas of ulceration as the most common finding, while Hunter and colleagues mentioned that a hypertrophic lesion is most common.7,10 Although involvement of the posterior larynx has been described classically, many reports have suggested that laryngeal TB has no predilection for any laryngeal site, and the true vocal folds have commonly been involved.6,9 Distinctively, patients may present with true vocal fold edema, which may be associated with an edematous “turban-shaped” epiglottis.7 This vocal fold involvement may explain the predominance of hoarseness in the clinical presentation of the disease. The patient in this case presented with a lesion that resembled a supraglottic papilloma. Interestingly, an excisional biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of squamous papilloma. Communication with the pathologist ensured that HPV and acid-fast stains were performed, making a true diagnosis possible. It is important to recognize that laryngeal tuberculosis may mimic squamous papilloma on laryngoscopy and histology.

It is also noteworthy that this patient was a young, immunocompetent female without recognized TB risk factors. Although males contribute more cases of laryngeal tuberculosis due to the overall male predominance in tuberculosis infections, female gender has been found to be an independent risk factor in the development of extrapulmonary tuberculosis.5 Furthermore, Wang and colleagues found that female patients presenting with laryngeal tuberculosis in Southeast Asia were significantly younger than male patients.9 Therefore, the clinician must include tuberculosis in the differential diagnosis, especially when a young female presents with irregular laryngeal lesions.

Conclusion:

Tuberculosis continues to be a global health problem. Therefore, it is important to include this disease in the differential diagnosis of irregular laryngeal lesions, especially in young females, even in the absence of other risk factors.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control 2011. Available at: www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en. Accessed May 8, 2012.

- Ferrara G, Murray M, Winthrop K, et al. Risk factors associated with pulmonary tuberculosis: smoking, diabetes and anti-TNFα drugs. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2012;18(3):233-240.

- Morán-Mendoza O, Marion SA, Elwood K, et al. Risk factors for developing tuberculosis: a 12-year follow-up of contacts of tuberculosis cases. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14(9):1112-1119.

- Topak M, Oysu C, Yelken K, et al. Laryngeal involvement in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265(3):327-330.

- Peto HM, Pratt RH, Harrington TA, et al. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(9):1350-1357.

- Yencha MW, Linfesty R, Blackmon A. Laryngeal tuberculosis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2000;21(2):122-126.

- Auerbach O. Laryngeal tuberculosis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1946;44:191-201.

- Harbersohn SJ. The treatment of laryngeal tuberculosis. J Laryngol. 1905;20:630-637.

- Wang CC, Lin CC, Wang CP, et al. Laryngeal tuberculosis: a review of 26 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(4):582-588.

- Hunter AM, Millar JW, Wightman AJ, et al. The changing pattern of laryngeal tuberculosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1981;95(4):393-398.

Leave a Reply