Ever since the first fully equipped otolaryngology team was sent to the Air Force Theater Hospital (AFTH) in Balad, Iraq in 2004, an otolaryngologist-head and neck surgeon has become a permanent member of any deployed multispecialty head and neck team, working alongside a neurosurgeon, ophthalmologist and oral and maxillofacial surgeon.

Explore This Issue

February 2010“Otolaryngologists are invaluable because of their specific skills which include acute airway management, upper airway endoscopy, neck trauma and exploration and soft tissue and bony facial trauma,” said Maj. Manuel Lopez, MD, chief of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at Wilford Hall Medical Center in San Antonio.

As with previous military conflicts, Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) in Afghanistan will probably bring about significant advances in trauma management and reconstruction of combat-related head, face and neck injuries (HFNIs). Some changes in the management of wound closures and infections, as well as the use of neck exploration, have already occurred.

“Certainly the evidence base from caring for these military wounds will enhance civilian care of traumatized patients, including those with head and neck and maxillofacial trauma,” said Richard Holt, MD, professor emeritus in the department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio. “For example, new biomaterials are already being investigated on the battlefield for control of hemorrhage and to enhance healing.”

In a war zone, clinical research is effectively driven by the great number of patients needing assistance. Since these studies are larger than most civilian studies, they provide more data and information for practicing U.S. otolaryngologists-head and neck surgeons. There are developing data from OIF or OEF regarding facial injury treatment and how that knowledge can be used to treat otolaryngology patients in the civilian world, according to Dr. Holt.

Wound Management

“During the Vietnam War, many traumatic wounds were contaminated and left open with a delayed closure planned for a medical facility outside of the country,” Dr. Holt said. “During OIF, in spite of the unusual microbes present, it was possible to deal with wounds more aggressively and perform primary closure, albeit with the utilization of key antibiotics, in theater, as Dr. Lopez reported in his study.”

In a 2007 report, Dr. Lopez described how, prior to 2005, most military personnel with facial fractures were air evacuated from AFTH (Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2007;9(6):400-405). These patients received definitive treatment of their wounds with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), because of concerns about sterility, infection from Acinetobacter baumannii, and delayed evacuation out of theater.

Dr. Lopez, however, reported that definitive treatment of facial fractures with ORIF might be feasible and safe in theater if certain criteria were met:

- The fracture site was exposed through either a soft tissue wound or because of an associated approach (e.g., a frontal sinus fracture exposed by a bicoronal flap during a decompression craniectomy)

- Definitive treatment of the fracture would not delay evacuation from the theater

- Treatment of the facial fracture would allow the patient to remain in theater

Delaying fracture fixation can increase infections, as well as technical difficulties, as surrounding facial muscles contract. Delayed treatment of jaw fractures may increase the odds of marginal nerve weakness and malocclusion. According to Dr. Lopez, primary closure of soft tissue defects by ORIF of facial fractures on initial presentation to a well-equipped in-theater hospital decreases the need for further facial surgery for patients when they return to the U.S.

Drs. Lopez and Holt agree that long-term reconstruction of badly traumatized faces will be advanced in the civilian community because of the experience gained by military surgeons and reported in specialty journals.

“Additionally, in Iraq and Afghanistan, local wound contaminants, such as Acinetobacter baumannii, can be an issue,” Dr. Holt said. “For U.S. civilians, it is methacillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). From Dr. Lopez’s work in closing wounds in Iraq using high-dose antibiotics and excellent attention to wound debridement and handling, more confidence is gained in the treatment of MSRA-contaminated wounds of the face, scalp and neck, and we can apply the same principles of care to this group of patients in the U.S.”

—Richard Holt, MD

Neck Exploration

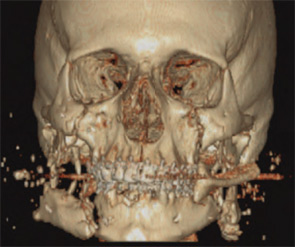

Data from the US Navy-Marine Corp Combat Trauma Registry reveals that almost 61 percent of all patients wounded during Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) have a head and neck wound and 65 percent of all HFNIs are to the face. The registry lists improvised explosive devices (IEDs) as the most frequent cause of HFNIs. IED shrapnel sprays upwards, causing complex facial lacerations, specifically small holes in the head and neck—areas not well protected by body armor. Although these high-velocity projectiles appear to just “nick” the skin, in reality they create serious pathology in the vascular structures of soft and hard tissues that can be difficult to detect.

Field experience has shown that early primary closure of these wounds will usually fail about five days post trauma due to tissue breakdown and necrosis, resulting in increased scarring and scar contracture which may negatively impact the success of reconstructive surgery (ADF Health. 2008;9(1):36-42). Therefore, even if patients appear asymptomatic, this type of high-velocity penetrating neck trauma mandates the consideration of neck exploration. In a 2006 study, COL Joseph Brennan, MD, from the Department of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery at Wilford Hall Medical Center, reported that the incidence of major intraoperative pathology found on exploration was 78 percent in patients with penetrating neck trauma (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(1):100-105). Relying only on imaging studies for neck exploration may result in a missed diagnosis.

Additionally, fragmentation wounds from IEDs are always contaminated because of the dirt, glass and metal found in them and require antibiotics such as cefazolin or clindamycin to combat Clostridium tetani and Bacteroides. Serial debridement and irrigation of these contaminants, as well as delayed wound closure, are crucial to preserving damaged soft tissue.

Based on the increasing number of HFNIs in OIF and OEF, the U.S. Army now has a wound management protocol in place for maxillofacial injuries that optimizes form and function outcomes for victims of IEDs, rocket propelled grenades, and high-velocity ballistics (ADF Health. 2008;9(1):36-42). “These advances include a better understanding of injury patterns from high velocity penetrating wounds, as well as an improved treatment algorithm,” Dr. Lopez said.

Bringing it Home

Dr. Holt acknowledged that deployed surgeons will someday be practicing in the civilian community after their military obligation is over and will bring their experiences to their communities and colleagues in otolaryngology.

“Since we are the ones deployed overseas to treat U.S. casualties, we can share directly with residents in training—the future leaders in military medicine,” said LCDR Robert M. Laughlin, DMD, interim director of Residency Training and staff surgeon in the Department of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery at Naval Medical Center in San Diego (NMCSD).

Physicians at NMCSD treat a broad range of combat-related head and neck wounds, including infections, airway management, nondisplaced facial fractures, lacerations and complex panfacial fractures, with and without significant avulsive tissue loss, often with loss of bony facial skeleton, as well as soft tissue injuries.

“We are applying our knowledge from head and neck cancer and large ablative surgeries to our wounded warriors with the application of free tissue transfers and large rotational flaps in order to restore form and function,” Dr. Laughlin said. “With these techniques, we are able to do a one stage versus multistage surgery, combining bony and soft tissue reconstruction. Although this technique is currently not done in theater, the surgeons on the front lines are cognizant of free tissue transfer and are preparing patients for this type of definitive care when they arrive stateside.”

The expertise gained by deployed otolaryngologists in OIF and OEF who have seen a large volume of HFNIs, has led to a renewed interest in HFNI trauma care by civilian otolaryngologists. “In fact, there is an effort underway, led by the military otolaryngologists, to refocus on our specialty’s experience and expertise in this aspect of trauma care,” Dr. Holt said.

More importantly, “as we become better educated and experienced in working with these technological advances, our service men and women are achieving better outcomes and reaping the benefits,” Dr. Laughlin added. ENTtoday

Leave a Reply