Explore This Issue

March 2014

The partial silence suffered by children with unilateral hearing loss (UHL) is too often met with an equal silence from school officials and even caregivers who, in many cases, fail to provide these children with the evaluations and interventions they need to cope with the effects of the hearing disability.

Judith E. C. Lieu, MD, associate professor and associate residency program director in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Washington University School of Medicine (WUSM) in St. Louis, said this awareness gap is partly due to outmoded yet persistent attitudes regarding UHL. “This has been going on for decades,” Dr. Lieu said. “It is the dominant attitude in schools, and I still hear it from some pediatricians. ‘Your child has one functioning ear; he or she will be okay,’ they’ll say. Well, we are accumulating enough evidence to suggest that they’re not necessarily okay: They are having difficulty in noisy classrooms, and they often can’t determine where sound is coming from. And so when their teacher calls on them and they don’t answer, or they are asked to put something away and they don’t respond, they’re often labeled as inattentive, slow learners, or worse.”

A 2010 study by Dr. Lieu and her colleagues at WUSM explored the link between UHL and developmental problems in children (Pediatrics. 125:e1348-e1355). The researchers measured speech-language performance in six- to 12-year-old children with UHL and compared the results with a control group of normal-hearing siblings (74 pairs, n=148) given the same tests. Children with UHL had lower scores than their siblings in three main areas of oral language performance: language comprehension (91 vs. 98; P=0.03), oral expression (94 vs. 101; P=0.007), and oral composite (90 vs. 99; P=0.01). Family income below the poverty level and lower maternal education levels were also associated with lower speech-language scores.

Further underscoring the effects of UHL on learning and behavior, the children with the hearing disorder had 4.4 times the risk of requiring an Individualized Educational Plan (IEP)—a sign of difficulty in school—and 2.5 times the risk of requiring speech therapy, the researchers noted.

Based on these results, Dr. Lieu and her colleagues called for rethinking how children with UHL are managed. “The common practice of withholding hearing-related accommodations from [these] children should be reconsidered and studied, and … parents and educators should be informed about the deleterious effects of UHL on oral language skills,” they concluded.

Overall Data

In 2012, Dr. Lieu’s research team continued to explore the interplay between UHL and childhood development by publishing the first study since 1976 to look at the problem using a longitudinal model (Laryngoscope. 2012;122:2088-2095). The study included 46 children with permanent UHL, ages 6 to 12 years, who were tested using standardized cognitive, achievement, and language testing at yearly intervals for three years. The researchers also looked at behavioral issues, as well as the degree to which interventions for UHL were offered to patients, such as IEPs and speech therapy. (By design, none of the children in the study were given any surgical or medical therapy for their hearing loss during the period of observation.)

—Judith E.C. Lieu, MD

The results were a bit of a mixed bag when it came to determining the extent to which UHL adversely affected the study participants’ development. Scores from standardized tests of language skills and cognition increased during the study, indicating that the children had some ability to overcome their hearing deficits, Dr. Lieu noted; however, “school performance [scores] did not show concomitant improvements.”

For example, rates of IEPs continued to be greater than 50% throughout the study, the investigators reported. And yet, in the majority of cases, Dr. Lieu noted, the IEPs did not include any provisions for the children to be tested for hearing loss or to be treated for the condition.

Dr. Lieu contends that a case could be made for 100% of children with UHL getting IEPs that include accommodations for their hearing impairment. But that is not happening, she noted, due to outmoded attitudes towards UHL. “This isn’t viewed as a disability by schools and insurers and other entities,” Dr. Lieu said. “And the logic of that escapes me. As I noted in our 2012 [Laryngoscope] study, having only one functional eye or hand is not challenged as being a disability; why, then, is unilateral hearing loss in kids often not taken seriously?”

Children who come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and have parents with low health literacy “are the kids I worry about the most, but they also can be the most responsive to interventions,” Dr. Lieu added. She explained that these pressures make it difficult for the children to compensate for their hearing loss on their own. “So, in our practice, we try to fit them with a hearing aid or some other intervention, and we often quickly see improvements in terms of avoiding or mitigating school performance issues and other problems. These kids can benefit an incredible amount from our efforts.”

Dr. Lieu acknowledged that the overall lack of data in this area makes it difficult to issue broad proclamations of which kids with UHL should get which particular type of intervention, and when. But that evidence gap should not cause any hesitation or delay in getting these children some type of help.

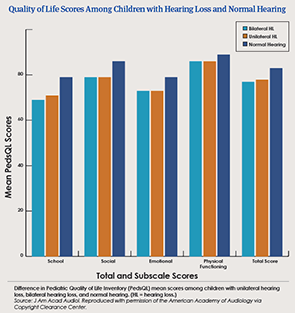

“What the studies do show conclusively is that children with UHL are not doing very well,” she said. “We have published quality-of-life surveys that illustrate this quite clearly [J Am Acad Audiol. 2011;22:644-653; Laryngoscope. 2014;124:570-578]. When you look at the data, you realize that these children are closer to their peers who have bilateral hearing loss than they are to peers with normal hearing. So, how can we not provide them with the best care we have to offer?” (See “Quality of Life Scores among Children with Hearing Loss and Normal Hearing).

Intervene Early—but Proceed with Caution

David M. Baguley, MBA, PhD, head of service: audiology/hearing implants at Cambridge University Hospitals, in Cambridge, England, agreed that although there is a lack of definitive data on managing UHL in children, “that does not justify a lack of action.”

“When we find evidence of hearing impairment in children, we do flag them for future interventions, and those efforts begin quite early,” Dr. Baguley said. “Certainly, by 4 years of age, we would be offering the patient and caregivers a plan for using CROS hearing aids or a similar, nonsurgical, fairly conservative treatment option.”

Moreover, it is important to remember that because the goal of treatment is to mitigate the psychosocial effects of the hearing loss, hearing aids should not be the only intervention offered. “We also reach out and talk with the child’s specialist teachers and explore whether loop hearing aids and other environmental sound reinforcements can be used, where possible, in the classrooms and other learning areas,” Dr. Baguley said.

Summing up, “I think the default is to intervene early, where appropriate, and to take a holistic approach,” he said. “But these are children, and again, the data on these management techniques are very limited. So we always proceed with caution.”

Dr. Lieu said that the research gap could be addressed with a study of controlled amplification to determine whether there is a clear benefit to language development and school performance. “I know there can be such benefits, but that’s based on my own empirical experience,” she said. “We need more data to show that definitively.”

Without such evidence, Dr. Lieu added, “my fear is that UHL will remain something of an invisible disability. And that’s not good for the patient, the family, the school—or the caregivers who are supposed to be advocating for these children.”

David Bronstein is a freelance medical writer based in New Jersey.

Leave a Reply