Explore This Issue

May 2014

When Albert Merati, MD, arrived as a laryngologist six years ago at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, his job was simple: Build up a practice by filling it with patients.

So he got out a piece of paper and wrote that down.

“The first step is very clear: Sit down with a piece of paper and write out your mission,” said Dr. Merati, chief of laryngology at UW’s department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. “Write out your goals and have a plan. There is no substitute for that.”

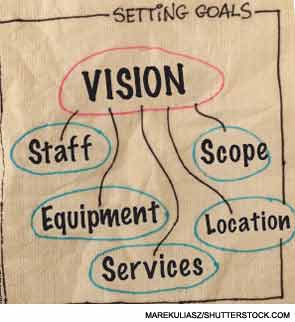

Otolaryngologists and a management consultant interviewed by ENTtoday agree that the key to setting up and running an otolaryngology practice is preparation. Budding otolaryngology entrepreneurs need to plan the scope of the practice, its staffing choices, its equipment purchases, and many other details as big as which electronic health record (EHR) system to use and as small as clauses in the office space lease agreement.

But it all starts with setting up a vision for the practice, said practice consultant Cheyenne Brinson, MBA, CPA, of KarenZupko and Associates (KZA) in Chicago.“You don’t know where you’re going if you don’t have a plan,” said Brinson. “Understanding where you want to go helps drive other decisions.”

Dr. Merati said that setting goals is his guiding philosophy each time he takes a new job to build up a practice’s patient load. “It’s not even patient specific,” he said. “It’s about fulfilling your personal and professional goals. If your goal is, ‘I want to be the best sinus surgeon in central Missouri, and I want to take care of patients with tough problems and make a difference in my community,’ then that’s what you write down. And then everything you do, every decision you make for your practice, should be mission driven. Step one for achieving a practice is [to] know what your goal is.”

Define Your Scope of Service

Steps two and beyond require additional planning in both the short and long term, said Brinson. Of course, it can be tricky to balance the up-front needs of a new practice against those that can arise if that business succeeds as planned. But Brinson, an instructor for KZA’s national coding and reimbursement workshops sponsored by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS), said keeping an eye on each goal simultaneously is important. “Focus on the short term, but keep the long-term goals in mind for the practice,” she said. “It’s a difficult balancing act to be sure.”

Defining scope of service is another challenge to starting a practice. Michael Setzen, MD, who opened his own private practice in Long Island, N.Y., in 2008 after 26 years in an academic setting, said otolaryngologists looking to set up shop first need to determine whether they will be fully aligned with an academic institution, independent, or part of a hybrid approach that affiliates a practice with an academic entity but is not formally dependent on the school.

Dr. Setzen, chief of the rhinology section at North Shore University Hospital in Manhasset, N.Y., said that alignment with a school involves specific details that require attention. “You do need to think about publishing, presenting,” he said. “Try to make an impact even though you are a private practitioner.”

Once the type of practice is determined, the next major decision is determining what services will be offered. Brinson said that understanding the market is key to making that choice. A geographic area saturated with audiologists or speech pathologists may mean that offering those services up front is an unnecessary cost. If those services aren’t easily available to a nascent practice’s potential patient base, then adding them might be a revenue driver.

Dr. Setzen said that when he opened his practice, equipment was a top concern. He decided that video, photo, and recording equipment would differentiate him from other otolaryngologists in his area. “I felt it was important to be able to show my patient, ‘This is what your deviated septum is and looks like,’” Dr. Setzen said. “Many patients would say, ‘Hey, doc, everybody has a deviated septum.’ And I could say, ‘Yes, but this is what you have. Do you see how deviated your septum is?’ A picture is worth a thousand words.”

Pictures aren’t cheap, though. Dr. Setzen’s video equipment cost roughly $75,000. He bought it on a five-year lease, a plan he suggests might be worthwhile to others looking to take advantage of expensive equipment without having to pay for it all up front. Other expensive equipment he leased that way included a computed tomography (CT) scanner. He noted that spending that money is a choice each otolaryngologist has to make.

Staffing Concerns

Another major challenge for any practice is staffing. Is an on-staff audiologist necessary? Should a speech pathologist be on site? What about a swallowing expert? Allergist? Dr. Merati believes that there is value in “lowering the barrier to access, letting the patients get to you as the expert, and then you can offer the services.”

The leaders of practices reliant on referral medicine should try to be as accommodating as possible for all patients, he said. Even if the patient has an issue that the private practitioner then has to send to someone else, a strong practice will get that referral first, Dr. Merati added.

“In the three academic jobs I’ve had, I had one goal. I wanted everyone in the hospital and everyone in the community to think: throat, Merati,” he said. “I wanted there to be a complete, unbreakable connection between that word and my name and not have people worry about, ‘Does this patient need a certain operation for a certain specific problem?’ I want them to think: This person has a throat problem. Send them to Merati.”

Dr. Setzen said that hiring staffers part-time can be a smart approach because it allows a practice to make the service available to patients at a fraction of the cost of a staff member who sees patients full-time.

Smart hires also help; for example, on a tight budget, your first receptionist could double as the medical assistant who works directly with patients. Then, there’s the all-important position of billing and coding staffer. Don’t scrimp there. “That’s a very critical need,” Dr. Setzen says. “Although the coding responsibility is predominantly and finally with the physician, you do need to work with someone who is a bit of a coding expert.”

Next Steps

Typically, once an entrepreneurial otolaryngologist has decided where the business will operate, how it will be staffed, and what equipment to buy, the rest of the decisions, while important, are a bit easier to manage. Choosing an EHR can be difficult, but it is often a matter of preferences and finding vendors. The situation is similar with malpractice insurance and credentialing with insurance plans. While these can be arduous processes, they tend to be less difficult than, say, connecting with a patient base in a community already served by other otolaryngologists.

Finally, Dr. Setzen likes to note, once the business has begun to operate well, don’t forget to keep planning for the future. “If you’re starting out as a new practitioner, you need to see how you’re developing, how the community is going to accept, how the referring physicians are going to accept you, and how you’re doing with your patients,” he said. “And then, if things are developing very positively, you enhance with another five-year plan.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance medical writer based in New Jersey.

Leave a Reply