Surgically releasing specific “trigger sites” may provide long-term relief for some sufferers of chronic migraine. According to a recent study published in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 88 percent of patients who underwent surgical deactivation of targeted trigger sites reported at least a 50 percent reduction in the frequency, severity and duration of their migraine headaches five years later (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):603-608).

Explore This Issue

May 2011Twenty-nine percent (20 patients) experienced complete relief, with no migraines reported over the five-year follow-up period. Fifty-nine percent of patients (41 patients) reported a significant decrease in headaches, while twelve percent (eight patients) reported no change.

But is the surgery ready for prime time? At least one otolaryngologist thinks so.

“The surgical treatment of migraines started about fifteen years ago, but some of what we’re doing has been around for decades,” said David Stepnick, MD, an associate professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio.

Septoplasty, for instance, can be used to relieve an intranasal migraine trigger site. Trigger sites in the forehead and temple area are treated with a surgical technique that evolved from an eyebrow lift, “something most of us in the ENT specialty of facial plastics already do,” Dr. Stepnick said. He currently uses surgery to release all four known trigger sites; to his knowledge, he is the only otolaryngologist/facial plastic surgeon in the U.S. to do so. (Plastic surgeons perform the bulk of surgical releases for migraine.) But Dr. Stepnick sees opportunity for other otolaryngologists. “We have the skill set to do all of the procedures that are currently out there,” he said.

Anatomical Basis

Greenfield Sluder, MD, a clinical professor and director of the department of laryngology and rhinology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo., linked headaches to nasal anatomy in the early years of the 20th century (JAMA.1919;72(12):885-886).

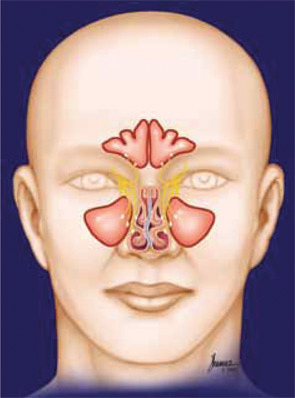

By the 1980s, otolaryngologists such as Heinz Stammberger, MD, G. Wolf, MD, and David Parsons, MD, had noticed that sinus surgery often relieved patients’ headaches (Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1988;134:3-23; Laryngoscope. 1998;108:696-702). CT scans of some patients revealed points of contact between the nasal turbinates and the septum; physicians theorized that the contact creates pressure and the release of substance P when the nasal membranes swell, thereby causing headaches. Surgical reduction of the turbinates removed the contact points, alleviating the intensity and frequency of headaches in over 75 percent of patients (Laryngoscope. 1998;108:696-702; Cephalalgia. 2005;25:439-443).

Meanwhile, Bahman Guyuron, MD, clinical professor and chairman of the department of plastic and reconstructive surgery at Case Western Reserve University, noticed that a number of his brow lift patients commented on a reduction in the severity and frequency of their headaches post-surgery (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106(2):429-437). Physicians were also beginning to use botulinum toxin type A (BOTOX) to successfully treat migraine. Dr. Guyuron theorized that migraines might be “related to the nerves being stimulated by the surrounding structures.”

Through anatomical study, Dr. Guyuron identified four points where muscles may compress peripheral nerves, triggering a migraine cascade: one in the forehead, one by the temples, one toward the base of the skull and any contact between the nasal turbinates and septum. He reasoned that if the injection of BOTOX in these areas (except the intranasal area) significantly reduced a patient’s headaches, surgical decompression of the trigger points might provide longer-lasting relief. In 2005, he demonstrated the efficacy of his idea: 92 percent of those (82 patients) who underwent surgical decompression of their trigger sites reported at least a 50 percent reduction in migraine frequency, duration or intensity (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(1):1-9). Later papers, including the recently published five-year outcome data, support his initial results (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(1):115-122; Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):461-468).

Identifying Appropriate Patients

Confirmation of a migraine diagnosis is essential before even considering surgical treatment. “I would never treat a patient unless they carry an official diagnosis of migraine headaches from a neurologist,” said Jeffrey Janis, MD, associate professor of plastic surgery at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. All patients included in the five-year study were initially examined by neurologists to confirm the diagnosis of migraine according to the guidelines established by the International Headache Society.

Ideal candidates are those who suffer from debilitating migraines that are unresponsive to other treatments or who can’t tolerate the side effects of migraine medication. “This is just not somebody who gets a migraine for three hours once in awhile and immediately responds to over-the-counter medication,” Dr. Guyuron said. He only operates on patients who suffer migraines—at least two a month—that negatively affect their quality of life. Lawrence Robbins, MD, a neurologist who specializes in the treatment of headaches, believes that surgery “may be a good option” for refractory migraine patients.

Systematic BOTOX injections are used to gauge the likelihood of surgical success. “BOTOX can be used as a test to see if one might respond to surgery,” said Dr. Janis, who uses a strict algorithmic approach to inject BOTOX into the migraine trigger points in the clinic setting. “If the BOTOX works, that’s a good sign the patient may be a good candidate for surgery. If the BOTOX doesn’t work, surgery may not necessarily be the best option,” Dr. Janis said. According to Dr. Guyuron, patients who suffer from nasal contact migraines must have clear findings of contact either via CT scan or physical examination before being approved for surgery.

Surgical Technique

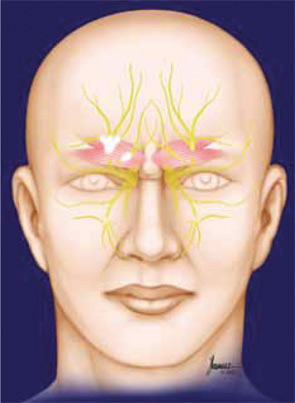

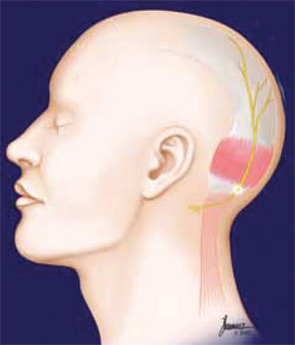

To relieve frontal trigger migraines, surgeons remove the glabellar muscle group, including the corrugator supercilii, depressor supercilii and procerus, through an upper eyelid incision, freeing the supraorbital and supratrochlear nerves. Temporal migraines are treated with the endoscopic removal of approximately three centimeters of the zygomaticotemporal branch of the trigeminal nerve to prevent its compression by the temporalis muscle (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(1):1-9; Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):461-468).

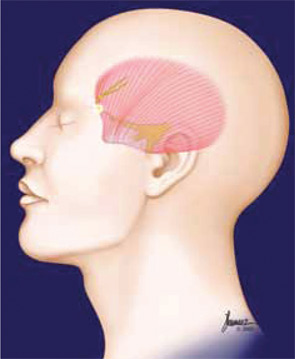

Removal of a small section (approx. 1 cm X 2.5 cm) of the semispinalis capitis muscle is part of the treatment for occipital migraines. Surgeons also create a subcutaneous flap to shield the greater occipital nerve from irritation. “It’s kind of like doing a superficial parotidectomy,” Dr. Stepnick said. “But the nerve in the partotid, the facial nerve, is actually much smaller and has many smaller branches. I actually think it’s easier to do the migraine nerve. It’s easier to find, and the nerve is bigger.”

Intranasal trigger points are treated with septoplasty and turbinate work. “You try to make sure that the turbinate is not touching the septum,” Dr. Stepnick said. “There are different ways to do that, and you choose the way based on the patient. One option is a therapeutic outfracture. You can also do a submucosal resection to take out the bony part of the turbinate.”

A word of caution: The existence of contact points is not an absolute indication for surgery. “The severity of contact points, or even their presence, does not translate to headaches. Minor contact points can induce severe headaches,” said Dr. David Parsons, clinical professor of pediatric otolaryngology at the Universities of North and South Carolina. Any decision to perform intranasal migraine surgery should be based on a patient’s history, not just on the existence of contact points as demonstrated by CT scan, he said.

Complications

To date, surgical complications have been minimal. Three of 69 patients reported some occipital stiffness or weakness at five years; some patients experience hypo- or hypersensitivity along the supraorbital or supratrochlear nerves (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):603-608). “A couple of patients have told us that they have muscle tightness, but I’m not sure if that’s related to the surgery, because muscle tightness is part of what causes occipital migraine headaches anyway,” Dr. Guyuron said. Other possible complications include minor muscle hollowing, eyelid ptosis, scalp itching and minor hair loss. At five years post-surgery, none of the patients examined by Dr. Guyuron’s team reported intense itching or uneven eyebrow movement; 20 of 79 patients experienced very occasional itching (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(2):603-608).

Dry nose and rhinorrhea have been reported in patients who underwent nasal surgery (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(1):1-9). Empty nose syndrome is a possible complication of turbinate removal, but “that’s not always done in every procedure,” Dr. Stepnick said. “Extensive, aggressive removal of the turbinates is not necessarily what’s being done in migraine surgery.”

Additional studies are needed to determine the long-term effects of surgical decompression, Dr. Lawrence said.

Further Considerations

Otolaryngologists interested in performing migraine surgery will “have to dedicate the time, the energy and the effort,” Dr. Janis said. “This is not something that can really be done on the side. You’re going to have to invest in some capital equipment because this does require surgical instrumentation, some of it endoscopic, and you’re going to have to learn the techniques.”

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine offers an Annual Symposium for the Surgical Treatment of Migraine Headaches that includes lectures, live surgery and cadaver dissection; this year’s symposium will be held Oct. 22 and 23. The American Society of Plastic Surgeons occasionally offers courses as well.

Dr. Guyuron is optimistic about the future of migraine surgery and the involvement of otolaryngologists. “I think there is an enormous role for ENT colleagues,” he said. “There are 30.5 million Americans suffering migraine headaches. Even if we serve just 10 percent of that population, that’s 3.5 million Americans.”

Leave a Reply