Image Credit: Living Art Enterprises/Science Source

The role of salvage surgery in patients with head and neck cancer is not a black and white issue but a complex one with high stakes for patients. Panelists gathered to take on the topic at the 2015 Triological Society Combined Sections Meeting, discussing the role of imaging in making the decision, recurrence management at the primary site and in the case of regional recurrence, and nonsurgical options.

Explore This Issue

April 2015Data on outcomes with salvage surgery make it clear that the procedure shouldn’t be treated as a fallback option—simply a way out if a first attempt at treatment fails, said panel moderator Randal Weber, MD, chair of head and neck surgery at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “With the exception of the larynx, patients don’t do very well if they fail the initial treatment,” he said. “I think it’s so important that we do the right thing initially for our patients to avoid the salvage scenario.”

When head and neck cancer recurs, options include salvage surgery with radiation or re-irradiation, single-modality radiation or re-irradiation with or without chemotherapy, or symptom management and palliative care.

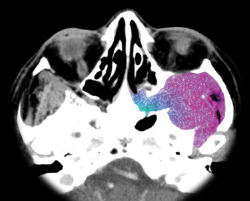

When thinking about salvage surgery, physicians should be sure to consider the patient’s fitness for surgery, rule out distant metastases using positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), provide realistic expectations to patients regarding the chances of a cure and their function after surgery, investigate the feasibility of the procedure, and take into account the possible need for reconstruction.

Role of Imaging

Surveillance is crucial for detecting the need for additional surgery early, and any change in symptoms should be considered recurrence until it’s proven not to be. Additionally, surveillance has to be individualized to account for specific patients’ circumstances, said Karen Pitman, MD, a head and neck surgeon with Banner Health in Arizona.

—Randal Weber, MD

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines suggest obtaining baseline imaging within six months of the initial procedure, but there are no guidelines beyond six months. Additional imaging should be guided by a change in symptoms and physical exams.

Baseline imaging is a way to account for treatment-related scarring, fibrosis, and inflammation. PET-CT is superior to CT-MRI alone in detecting residual disease, with a sensitivity of 94%, a negative predictive value of 95%, a specificity of 82%, and a positive predictive value of 75%. Reasons for false positives can include performance of imaging too soon after treatment, inflammation, infection, and normal physiological uptake of the tracer used.