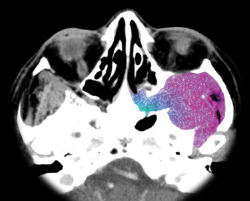

Image Credit: Living Art Enterprises/Science Source

The role of salvage surgery in patients with head and neck cancer is not a black and white issue but a complex one with high stakes for patients. Panelists gathered to take on the topic at the 2015 Triological Society Combined Sections Meeting, discussing the role of imaging in making the decision, recurrence management at the primary site and in the case of regional recurrence, and nonsurgical options.

Explore This Issue

April 2015Data on outcomes with salvage surgery make it clear that the procedure shouldn’t be treated as a fallback option—simply a way out if a first attempt at treatment fails, said panel moderator Randal Weber, MD, chair of head and neck surgery at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “With the exception of the larynx, patients don’t do very well if they fail the initial treatment,” he said. “I think it’s so important that we do the right thing initially for our patients to avoid the salvage scenario.”

When head and neck cancer recurs, options include salvage surgery with radiation or re-irradiation, single-modality radiation or re-irradiation with or without chemotherapy, or symptom management and palliative care.

When thinking about salvage surgery, physicians should be sure to consider the patient’s fitness for surgery, rule out distant metastases using positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), provide realistic expectations to patients regarding the chances of a cure and their function after surgery, investigate the feasibility of the procedure, and take into account the possible need for reconstruction.

Role of Imaging

Surveillance is crucial for detecting the need for additional surgery early, and any change in symptoms should be considered recurrence until it’s proven not to be. Additionally, surveillance has to be individualized to account for specific patients’ circumstances, said Karen Pitman, MD, a head and neck surgeon with Banner Health in Arizona.

—Randal Weber, MD

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines suggest obtaining baseline imaging within six months of the initial procedure, but there are no guidelines beyond six months. Additional imaging should be guided by a change in symptoms and physical exams.

Baseline imaging is a way to account for treatment-related scarring, fibrosis, and inflammation. PET-CT is superior to CT-MRI alone in detecting residual disease, with a sensitivity of 94%, a negative predictive value of 95%, a specificity of 82%, and a positive predictive value of 75%. Reasons for false positives can include performance of imaging too soon after treatment, inflammation, infection, and normal physiological uptake of the tracer used.

The goal of imaging is to establish the “new normal,” which is important for future comparison, Dr. Pitman said. She added that there is room for improvement in having more standardized imaging protocols during surveillance. “There are no good NCCN guidelines for surveillance and follow-up,” she said. “We need cost-effective surveillance imaging guidlines that take into account disease site and individual patient factors.”

(click for larger image)

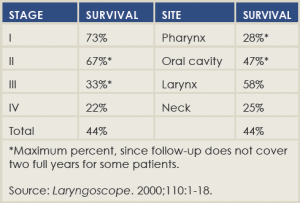

Two-Year Disease-Free Survival After Salvage Surgery

Recurrence at the Primary Site

Pierre Lavertu, MD, director of head and neck surgery and oncology at University Hospitals in Cleveland, said that two-thirds of patients with a primary recurrence are going to be salvageable. There are considerations that might run counter to surgery, however, including distant metastases, whether or not the disease is considered resectable, patients who are medically unfit for surgery, or those who simply prefer not to undergo surgery.

Surgery comes with complications, which are encountered in 23% to 64% of procedures, said Dr. Lavertu.

He mentioned a 2000 paper, published in The Laryngoscope and still considered an important salvage surgery study, that found that median disease-free survival correlated strongly with recurrent stage but weakly with the site of recurrence, and didn’t correlate at all with time to pre-salvage recurrence (Laryngoscope. 2000;110[3 Pt 2 Suppl 93]:1-18) (See “Two Year Disease-Free Survival After Salvage Surgery,”).

In a study of his own of 73 patients seen consecutively over a six-year period, Dr. Lavertu found that five-year disease-free survival was 41.6% and overall five-year survival was 51.6%. “Surgery is definitely the best option if we have tumor recurrence,” he said. “It’s not possible in all patients. The extent of surgery is according to the T stage, with the exception of the larynx, where most people end up with a laryngectomy.” He added, “We have to expect and be ready for complications and be ready to minimize these complications with the use of reconstruction.”

Regional Recurrence

Patients with no prior surgery or recurrence have the most favorable outlook when it comes to salvage surgery with regional recurrence, followed by those with no surgery but radiation alone and then those who’ve had surgery but no radiation, said Dennis Kraus, MD, director of the center for head and neck oncology within the New York Head and Neck Institute and the North Shore-LIJ Cancer Institute in the North Shore-LIJ Health System in New York City. “Unfortunately, the group that represents the majority of patients, that at least I see in my practice, are patients who had a neck dissection, they’ve been irradiated, and they’ve recurred in the neck,” he said.

Factors affecting resectability include carotid resection and reconstruction, infiltration of the skin, deep neck musculature involvement, brachial cranial neuropathy, and invasion of the mandible.

In one study of 943 patients with primary head and neck tumors, 95 had isolated neck recurrences—49 ipsilaterally, 36 contralaterally, five bilaterally, and two unknown (J Oncol. 2012;154303). Salvage surgery attempts were made in about half the patients, with re-irradiation when possible. Overall control was achieved for 31%—25% on the ipsilateral side and 37% on the contralateral side.

“Patient selection is critical,” Dr. Kraus said. “Surgical management is dependent on the prior treatment. It’s critical that we have a surgical roadmap for planning these cases …. Ultimately, there is an overall poor outcome for this population of patients.”

Nonsurgical Options

Recurrent head and neck cancer is a major challenge because patients have received so much radiation already, said Cherie-Ann Nathan, MD, chair, professor, and director of head and neck surgical oncology and cancer research at Louisiana State University’s Feist-Weiller Cancer Center in Shreveport. Chemotherapy is really the gold standard, with response rates between 10% and 40% but a “dismal” overall survival of just five to nine months, she said.

With re-irradiation plus chemotherapy, the median overall survival is 11 to 12 months, regardless of the combination of agents used. Radiation performed in the post-operative setting following resection yields significant improvement in local and regional control when compared with resection alone. But, surprisingly, it yields no difference in overall survival.

A study from Sloan-Kettering found that intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) brings a better progression-free probability compared with non-IMRT treatment (Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:57-62). A 2007 study of cetuximab as a single agent in patients with disease progression on platinum therapy found survival probability was improved by about two months when compared with cetuximab plus platinum combination regimens (J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2171-2177).

“The question we should ask is, although there’s a significant difference in many of these trials, does five months versus seven months make a difference?” Dr. Nathan said. If not, then palliative care should be strongly considered. Factors to think about are events the patient may want to attend, quality of life, and symptoms. “We have this big divide between curative care and palliative care, but those lines are now crossing.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.