Explore This Issue

May 2014

Recently published data that adds to the accumulating evidence suggesting that the rapid rise in thyroid cancer represents an epidemic of diagnosis rather than disease is increasingly challenging otolaryngologists and other clinicians to rethink both the diagnosis and treatment of specific thyroid cancers—namely, small papillary thyroid cancers.

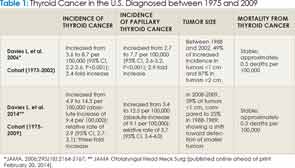

In their most recent study, which looked at the incidence of thyroid cancer diagnosed between 1975 and 2009 in the United States, Louise Davies, MD, MS, of the White River Junction VA Medical Center, and H. Gilbert Welch, MD, MPH, of the Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., report that the incidence of thyroid cancer nearly tripled and that nearly the entire increase in thyroid cancer diagnoses was due to papillary thyroid cancer. Published online in JAMA in February 2014, the study confirms the findings reported by the investigators in 2006 in their first seminal study, which showed a doubling of papillary thyroid cancer diagnoses from 1975 to 2002, with 87% of the increase in tumors 2 cm or smaller. Using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program and data on thyroid cancer mortality from the National Vital Statistics System, both studies also showed that during these years thyroid cancer mortality remained stable (see Table 1).

What emerged from these studies is a growing recognition among many clinicians of the overdiagnosis and subsequent overtreatment of thyroid cancers that will never cause symptoms or death. This recognition has created the need to address the overdiagnosis of thyroid cancer on two fronts: 1) reducing the number of small papillary cancers of the thyroid that are identified and 2) rethinking the management of biopsy-proven small papillary thyroid cancer.

Underlying this discussion is a strong recognition of the need to educate patients on the risks and benefits of diagnosing and treating these small papillary tumors, most of which will never create problems.

“Otolaryngologists are key in the solution to avoid overdiagnosis and overtreatment of thyroid cancer,” said Juan P. Brito, MBBS, Knowledge and Evaluation Research Unit, division of endocrinology, diabetes, metabolism, and nutrition, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. “Many patients with small papillary lesions receive therapies designed for more aggressive tumors. Otolaryngologists who are willing to avoid unnecessary therapies should incorporate the values and preferences of the patients in the decision-making process and start by telling patients what their options are and the advantages and disadvantages to each option.”

*JAMA. 2006;295(18):2164-2167; ** JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg [published online ahead of print February 20, 2014].

The Gauntlet Is Down: Toward a Patient-Centered Practice

According to Luc G. T. Morris, MD, an otolaryngologist on the head and neck service in the department of surgery at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, N.Y., the real controversy for most otolaryngologists, and the area in which a consensus in the specialty is needed, is what to do with a patient who has a biopsy-proven cancer of a small nodule that should not have been biopsied.

“The prevailing viewpoint of surgeons when they are referred a patient with a smaller than 1 cm thyroid cancer or microcarcinoma is to feel obligated to remove it, despite thinking that the nodule should not have been biopsied in the first place,” he said. This is considered standard of care as recommended by the current American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines; however, Dr. Morris emphasized that this recommendation has created a disconnect in thinking among otolaryngologists and other physicians managing thyroid cancer. The disconnect, he said, is that the guidelines say that it is unnecessary to biopsy small (1 cm or less) thyroid lesions, because cancers this size are believed to be clinically insignificant; however, if these small lesions are biopsied, surgeons feel compelled to treat them as clinically significant (i.e., perform a thyroidectomy).

He emphasized, however, that just because it is now known that a small thyroid nodule is cancer does not change the fact that it is a low-risk cancer with generally indolent behavior.

Based on this fact, he and his colleagues at Memorial-Sloan Kettering currently give patients who present with small papillary thyroid cancers the option of surgery or active surveillance. Active surveillance usually consists of following the patient with an ultrasound every six months for two years and once a year after that. He and his colleagues offer this to patients with cancers up to 1.5 cm in size. Over 80% of patients who have been offered active surveillance at Memorial Sloan-Kettering chose that option over surgery, he said.

R. Michael Tuttle, MD, an endocrinologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, is a lead investigator on a long-term observational study looking at outcomes of about 100 enrolled patients who chose active surveillance. All patients in the study are 18 years of age or older, with 1-cm lesions confined to the thyroid and no abnormal lymph nodes as detected by ultrasound. To date, he said, the patients have been followed for two to three years, and about 90% of patients have no change in their lesions. In 10% of patients with slowly growing tumors, surgery was performed. Dr. Tuttle emphasized that these data mirror what the Japanese have been reporting for years (see Table 2).

“We are very nicely reproducing the Japanese experience, and if this works over the next 100 or so patients, I think it will give us all the comfort in properly selected patients to say that we don’t need to rush to surgery and we can watch these lesions,” he said.

According to Dr. Tuttle, it is still unclear in which patients tumors may grow, and part of the study is to help figure that out. Preliminary data suggest that tumors may grow more in younger patients than in older ones, and that pregnancy may also influence tumor growth.

For Dr. Brito, the key is to educate patients and work with them to tailor the treatment so that it fits. “Clinicians need to elicit the preference of the patient and accommodate the treatment that fits the patient’s context,” he said. “For instance, a 70-year-old man with another more aggressive malignancy might want to opt for active surveillance, as may a 32-year-old actress who is concerned about a neck scar from surgery. A 43-year-old executive, on the other hand, may be too concerned about metastasis and opt for surgery.”

Brian Burkey, MD, head and neck surgeon in the Cleveland Clinic Head and Neck Institute in Ohio, agreed that treatments for individual patients should be determined by specific patient factors and by “rich and meaningful discussions with the patient concerning subsequent options for treatment and their respective risks and benefits,” but he also emphasized the need to follow the ATA’s current evidenced-based guidelines on the treatment of thyroid nodules and well-differentiated thyroid cancer.

“Active treatment of thyroid cancer is currently the standard of care and, as such, should be the default method,” he said. “Novel treatments of thyroid cancer, such as observation alone, should be studied by the experts in a protocol setting before being widely adopted.”

Although most otolaryngologists currently do not offer active surveillance in patients with biopsy-proven thyroid cancer, Dr. Tuttle thinks otolaryngologists are heading in that direction. “Most otolaryngologists wish that endocrinologists were not biopsying these small nodules in 70-year-old patients,” he said.

He also emphasized that, once a lesion is biopsied, otolaryngologists do not need to rush to surgery. “The data show we don’t have to hurry,” he said. “Things are not going to get out of control in a year or two, and so the treating otolaryngologist can feel comfortable telling the patient that it is reasonable to watch the lesion, just as we tell men with prostate cancer and older patients with lymphoma.”

Looking Too Hard for Thyroid Cancer?

According to Dr. Morris, current guidelines by the ATA, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, and the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound clearly recommend against performing a fine needle biopsy of a thyroid nodule smaller than 1 cm, except in rare cases such as those involving patients with prior radiation exposure (see “Guidelines for Management of Thyroid Cancer,” below).

Although he thinks most otolaryngologists are aware that these small nodules should not be biopsied, he said that many endocrinologists and other clinicians, including some otolaryngologists, still persist in biopsying them.

Laura Esserman, MD, MBA, director of the University of California at San Francisco’s Carol Franc Buck Breast Cancer Center and professor of surgery and radiology at UCSF, who coauthored a recent JAMA editorial (2013;310:797-798) on the growing issue of overdiagnosis in cancer, emphasized that better detection is not always a good thing and that the vast majority of small papillary lesions are relatively indolent. As such, she encourages physicians to call them “something less scary than thyroid cancer and to wait to intervene if there is evidence of progression. “Reassure patients,” she said. “At the end of the day, our oath is to do no harm.”

Dr. Burkey, on the other hand, sees little downside to the increased detection of smaller cancers. “There is good data to suggest that treatment of smaller and lower-stage thyroid cancers results in better survival and less extensive surgery than larger cancers,” he said.

An increasing issue in overdiagnosis is the detection of these small nodules as an incidental finding. According to Dr. Brito, in an editorial published in 2014, the incidental discovery of thyroid cancer in the United States due to the constantly increasing trend in the use of imaging, has contributed significantly to the rapid increase in thyroid cancer detection (Future Oncol. 2014;10:1-4).

According to Dr. Davies, an associate professor of surgery in the section of otolaryngology in the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College, a key message of her study is the need for better recognition of how to consider and manage these incidental small tumors. “Small, incidentally identified thyroid nodules should be recognized as such by surgeons, and an open discussion about the pros and cons of workup and surgery should be had with every patient, so they fully understand the benefits and potential harms of undergoing treatment for small, incidental, asymptomatic findings,” she said.

She also emphasized the need to revisit the threshold to biopsy small, incidentally detected thyroid nodules, saying that the threshold has likely fallen too far.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical writer based in Minnesota.

Leave a Reply