Explore This Issue

April 2014

One of the most frustrating experiences for a physician is treating a patient whose symptoms do not resolve. Approximately 10% of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients pose a challenge to physicians, meeting the clinical parameters of successful treatment while still being plagued with excessive daytime sleepiness (Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:601-608). This symptom affects more than quality of life. It can impair the ability to concentrate and remember and, more seriously, significantly raise the risk of automobile accidents (Eur Respir J. 2009;34:687-693).

More than 18 million adults suffer from OSA, and the condition’s chronic oxygen starvation, coupled with disturbed sleep, increases the risk of hypertension, heart disease, mood disorders, and metabolic problems. Most patients are treated with a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device. Success is achieved when the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) is reduced to less than five, or when AHI falls between five and 15 and symptoms have been resolved.

However, approximately one in 10 patients experiences significant daytime sleepiness despite CPAP use and a normalization of AHI, a disheartening outcome for patients with OSA. Pell Ann Wardrop, MD, medical director of the St. Joseph Sleep Wellness Center in Lexington, Ky., and ENTtoday editorial advisory board member, said otolaryngologists should do a better job of managing patient expectations. “We need to tell patients that we are going to improve physiological parameters, [and] we will make you feel better, but we may not completely resolve your sleepiness,” she added.

Kathleen Yaremchuk, MD, chair of the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, recommends administering the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), a validated questionnaire that evaluates level of daily sleepiness by asking patients to assess their likelihood of dozing in eight different situations (available at epworthsleepinessscale.com). A score of 10 or higher is considered abnormal. Dr. Yaremchuk said, “It is important to administer an ESS to see how much patients’ symptoms have improved over their pre-treatment sleepiness level. If they were a 14 before treatment and a 12 after, you need to look for another cause beyond OSA.”

Although getting to the root of the problem may be challenging, a thorough and methodical exploration can very often reveal the underlying cause of sleepiness, pointing you toward actionable steps to resolve the issue.

Searching for the Cause: Improper CPAP Use

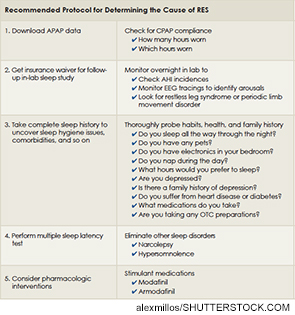

One common cause of residual excess sleepiness (RES), and a good place to start the investigation, is incorrect CPAP titration. Thanks to new insurance regulations, the days of OSA patients using conventional CPAP devices with customized air pressure settings are over. Similarly, it is no longer the norm for a patient to return to the lab one month into CPAP treatment to undergo an overnight in-lab CPAP titration study during which AHI is measured and electroencephalogram (EEG) tracings are monitored to check for arousals. Patients now are given an automatically adjusting CPAP machine, or AutoPAP (APAP), which auto-adjusts air pressure from a range programmed in by the otolaryngologist. In place of the titration study, the machine uses a proprietary algorithm to determine AHI incidences, and there is no EEG. The data is stored in the APAP computer and can be downloaded by a sleep professional to gauge the patient’s progress.

APAP users with excessive daytime sleepiness do have some recourse. Physicians can usually receive approval from the insurance company for a traditional in-lab study that will hopefully capture data not recorded by the APAP. EEG tracings can identify arousals, and electrodes attached to the legs can discover restless leg syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. But insurance approval may not be the only hurdle to overcome. Many people now have high co-pays and large deductibles that can make this additional test a hardship.

In addition to incorrect titration, poor CPAP compliance could be a culprit. CMS defines compliance as wearing the mask four hours a night for five nights a week, but this amounts to only 20 hours of sleep per week, which is less than half of what adults actually require. Some patients are minimally compliant, meeting the technical definition of proper use but not using the device enough to make a meaningful impact on their sleep health. Others see CPAP as a kind of “magic bullet” that will allow them to obtain adequate rest from just four or five hours of sleep.

When searching for the cause of RES, physicians should begin by examining the download from the APAP device. This will give a snapshot of patient compliance, including how many hours they wear the mask and, very importantly, which hours they wear it. Dr. Wardrop pointed out, “A person can be officially compliant, wearing their APAP from 11:00 p.m. to 3:00 a.m. every night, but miss the main hours of REM sleep between 3:00 a.m. and 6:00 a.m., when sleep apnea is at its worst.”

Not all noncompliance is intentional. Some people unknowingly remove the mask during sleep. CPAP machines have alarms that sound when this happens, but, ironically, patients often sleep right through them. Counsel patients to make certain the alarm is on and the volume turned all the way up, and enlist bed partners to wake the patient when they hear it go off or when they hear snoring. If the patient cannot break this habit, he may be a candidate for a mandibular advancement device.

Uncovering the Issues: A Complete Sleep History

When a patient is being treated for OSA, it is tempting to assume that RES is tied to this condition in some way; however, there may be other causes. Lee Shangold, MD, otolaryngologist and sleep lab director at ENT and Allergy Associates, LLP, in Port Jefferson, N.Y., advised, “If patients are getting optimal CPAP treatment, the next step is to go through the differential diagnoses to determine what else could be contributing to their excessive sleepiness.”

It is vital to take a complete sleep history that includes a wide range of questions addressing habits, health, and family history. The largest culprit in daytime sleepiness, in OSA patients and in the general population, is insufficient sleep. When questioned, many patients report that they are in bed for eight hours, yet they are still tired during the day. In these cases, it is important to probe deeper with questions like:

- Do you sleep through the night? Many patients wake in the middle of the night and watch TV for two hours before falling back to sleep.

- Do you have any pets? According to the CDC, 56% of dog owners and 62% of cat owners report sleeping with their pets, who may disturb their owners with movements and crowding.

- Do you keep any electronics in your room? A TV, computer, cell phone, or tablet can be particularly problematic for children and adolescents.

- Do you nap during the day? A two or three hour nap in the afternoon may prevent patients from being tired enough to fall asleep at bedtime.

The answers to these questions may uncover bad sleep habits that are the real cause of their RES. According to Dr. Shangold, “People sleep four hours and wonder why they are tired. They are tired because they sleep four hours.” These patients may be able to resolve their symptoms by improving their sleep hygiene.

Interestingly, younger patients are more likely to suffer from RES. Although the reason for this is not known, Annelies Verbruggen, MD, otolaryngologist in the department of head and neck surgery at Antwerp University Hospital in Antwerp, Belgium, suggested, “Younger patients often have a more active life: They experience more professional stress and have young children who interrupt their sleep. This could make them more tired.”

Not all RES is behaviorally induced. Many OSA patients have more than one sleep disorder contributing to their symptoms. A careful sleep history can uncover a circadian rhythm disorder. Asking people what hours they would like to sleep if they had no work responsibilities, or what time they rise on weekends or on vacations, can provide a clue to how well they are responding to environmental cues.

If the sleep history fails to uncover the cause, more aggressive testing may be in order. A multiple sleep latency test can identify narcolepsy or hypersomnolence, but only if it is performed under the proper conditions. Patients who are not on regular sleep cycles, who did not get at least six hours of sleep the night before, or who have stimulant or sedating medications in their systems will not obtain valid results.

Beyond sleep disorders, several comorbidities contribute to excessive sleepiness. Diabetes can cause fatigue, and medications for heart disease are often sedating. It is important to make sure you have a complete picture of any other health conditions and all medications a patient is taking. Ask directly about OTC products; patients often leave them out, thinking they are not relevant because they are non-prescription. You may find out a patient is taking an OTC sleep formulation that contains Benadryl.

The largest comorbidity contributing to excessive sleepiness is depression. Dr. Shangold pointed out, “With depression, there are disturbances in the pathways that regulate sleep and wakefulness. Also, many depression patients may be on medication with a sedating effect.” Bear in mind that not everyone suffering from depression has been diagnosed. Even if the patient tells you she is not depressed, probe into any family history of depression while taking the sleep history.

There is a small subset of patients for whom the cause of excessive daytime sleepiness remains a mystery. After every other possibility is exhausted, it may be necessary to prescribe modafinil (Provigil) or armodafinil (Nuvigil) as a stimulant. This therapy has been proven effective over the years, with many patients experiencing significant increases in wakefulness and daytime function (Chest. 2003;124:2192-2199; J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:751-757). Modafinil has not demonstrated dangerous adverse effects in clinical studies, although none were longer than 12 weeks, said Dr. Shangold. Some patients do experience headaches and personality effects, particularly a tendency to speak their minds more candidly. Dr. Wardrop added, “You have to be careful you aren’t treating sleep deprivation with a stimulant. If they are not wearing their CPAP enough, or not sleeping enough, you do not want to give them a stimulant so they can continue to do that.”

Finding the underlying cause of RES requires a commitment from the sleep professional, but it is important to put in the time and effort. As Dr. Yaremchuk said, “Do not give up when looking for a solution for excessive sleepiness. There is always something that can be done to help these patients feel better.”

Maybelle Cowan-Lincoln is a freelance medical writer based in Morris Plains, N.J.

Leave a Reply