Explore This Issue

September 2011Fat grafts have been used to repair the aging face for about two decades, but recently, surgeons have been using grafts to repair more extensive facial deformities caused by injury, illness or congenital abnormalities. Success, they said in interviews with ENT Today, depends on proper patient selection, matching the fat graft to defects that are most amenable to repair with fat injections and an understanding of the biology of the graft and how it reacts with surrounding facial structures.

Samuel M. Lam, MD, a plastic surgeon in Plano, Texas, and co-author of “Complementary Fat Grafting” [Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006], told ENT Today that although fat transfers for the aging face can yield impressive results, the nature of grafts means inherent risks that limit their potential in the repair of more extensive soft tissue trauma.

“Fat is a live graft; it’s not a bioinert substance like Restylane or other injectable filler products. So it carries with it a certain level of morbidity that we don’t always appreciate,” Dr. Lam said. He noted, for example, that fat grafts can change in volume and shape as a result of weight loss or weight gain. This makes fat grafts a poor choice in the younger, metabolically active patient who has experienced a traumatic injury or extensive surgical excision and requires a large area of correction.

“I’ve seen these patients earlier in my practice. They gain 20 to 30 pounds after fat transfer, and their faces look bloated and even distorted,” he said.

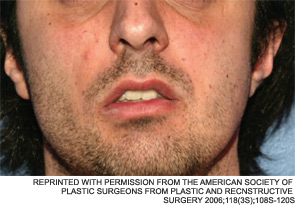

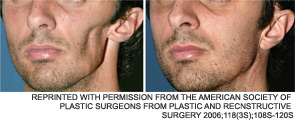

Dr. Lam said that such suboptimal outcomes are certainly not limited to his own experience. He knows of cases in other practices where problems arose from using fat grafts in metabolically active patients. In one such case, which he detailed in a paper on the “do’s and don’ts” of fat transfers for soft tissue trauma (Facial Plast Surg. 2010;26(6):488-493), a colleague employed a fat transfer to treat a young woman with a unilateral mandibular defect. “About 18 months after the procedure,” Dr. Lam said, “the graft had attracted a blood supply and had grown to the point where she developed a very noticeable protuberant deformity—it actually looked like a tumor.”

A better choice in such cases, he noted, would be to use a removable alloplastic material such as silicone to correct the defect “as long as there is enough soft tissue coverage to ensure that the implant will not be exposed.”

Larger Defects Require More than Fat

Other plastic surgeons echoed Dr. Lam’s contention that the cases for which such an approach might work are limited.

“There really aren’t a lot of clinical situations where surgeons are successfully injecting large volumes of fat into those types of defects,” said Craig D. Friedman, MD, FACS, a facial plastic surgeon with a private practice in Wilton, Conn., and a visiting surgeon at Yale-New Haven Hospital in New Haven, Conn. According to Dr. Friedman, the general trend in such cases, at least in the past decade, has been to use free flaps that not only contain fat, but also include some combination of blood vessels, tissue, muscle and fascia. These grafts “come with their own blood supply and achieve much better peripheral tissue integration” than would an injection of lipo-aspirated abdominal fat, he said.

There are instances where fat grafts can work, with some limitations, in moderately larger defects. “In the lateral parotid mandible area, where you’ve done a radical extirpation of malignant tissue or congenital/traumatic defect, fat grafts are still a viable corrective approach,” Dr. Friedman said. “But it’s by no means a perfect solution. There will be volume resorption of the fat, so repeat procedures could be needed.”

When faced with more moderate soft tissue defects, Dr. Friedman said he relies primarily on processed tissues and adjunctive biomaterial fillers such as Alloderm, which is made from donated human cadaver skin. In fact, the logic of using a fat graft even for these moderate-sized defects “eludes me,” he said. In such cases, “you have to overtransplant with the fat graft, because it’s hard to predict how much volume you’re going to end up with. If that’s the case, why not use processed tissue? It’s much more predictable, it vascularizes nicely, it’s a terminally sterilized substance and it does a good job of preserving all of the extracellular matrixes, microvessel structures and other types of tissue architecture that are important for the tissue to be incorporated into the defect and yield an optimal cosmetic result.”

“With our approach, we’re not using a flap at all; we simply excise a volume of fat with a layer of its overlying dermis attached.”

“With our approach, we’re not using a flap at all; we simply excise a volume of fat with a layer of its overlying dermis attached.”

—James L. Netterville, MD

A Combined Approach

James L. Netterville, MD, director of head and neck surgical oncology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in Nashville, Tenn., advocates a combined approach for repairing extensive soft tissue defects. His procedure of choice uses free dermal fat grafts (FDFG), which contain not only fat, but also an overlying layer of dermis. According to Dr. Netterville, the grafts can be used to fill in large facial defects following parotidectomies and other extensive head and neck surgeries, “with excellent cosmetic results and long-term outcomes.”

Dr. Netterville is the senior author of a poster study of the procedure presented by one of his residents, Sanjay M. Athavale, MD, at the 2011 Triological Society annual meeting in Chicago (A182. Free dermal fat graft reconstruction of the head and neck: a cosmetically appealing reconstructive option). The study showed a very low incidence of side effects: Only three of 62 patients in the study (4.8 percent) experienced a complication related to their FDFG recipient sites, Dr. Athavale reported. Moreover, none of the patients had abdominal donor site complications.

As for postoperative cosmetic results, those were assessed with “a novel patient-based numeric grading scale,” Dr. Athavale said. The grading scale yielded very high numerical levels of patient satisfaction (an average 4.9 out of 5), leading the authors to conclude that the technique “can be used in a variety of locations and patients tend to be very happy with their final cosmetic outcome.”

Dr. Netterville told ENT Today that although he was impressed with the results detailed in the poster, those numbers tell only part of the story. He stressed the “hugely important” economic benefit to using FDFGs, rather than other, more extensive surgeries, such as free flap transfers. With the latter approach, he said, hours of microsurgery are required to attach the free flaps to the vasculature of the donor site, resulting in hundreds of thousands of dollars in health care costs. “With our approach, we’re not using a flap at all; we simply excise a volume of fat with a layer of its overlying dermis attached. It’s a much simpler procedure, and it only incurs about a $1,500 cost to the health care system.”

Dr. Netterville added that he does not use electrocautery to harvest the free fat graft “so that we don’t damage any of the fat cells. I can’t prove it, but I feel strongly that is a key to our success with the procedure. Lots of other surgeons use electrocautery, and I really think it contributes to poorer outcomes.”

Fat Grafts and War Injuries

Still, there are surgeons who push the envelope when it comes to using fat grafts without any dermis or other structures attached to repair major facial deformities. Two noted proponents of fat grafting, Sydney R. Coleman, MD, a plastic surgeon in New York City, and J. Peter Rubin, MD, chief of plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC), have been using the grafts in soldiers with extensive soft tissue injuries incurred during the war in Iraq. The surgeons rely on fat harvesting, processing and injecting techniques that have been developed and continually refined over the past decade by Dr. Coleman (Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33(4):567-577), who visits UPMC regularly to assist in the procedures.

“The effects we’ve achieved in some of these soldiers [are] pretty remarkable,” Dr. Coleman told ENT Today. “We’ve actually filled in some huge craniotomy defects that had left the patients with just skin over metal mesh, with no place to put anything, and yet we’ve been able to get some remarkable filling of those defects and improved facial scarring as well. So it’s not just big holes we’re filling.”

Asked to explain how fat, which does not have much structure or “lift,” could not only fill but also support facial contours in such defects, Dr. Coleman replied that it is probably due to the stem cells in the grafted fat that he maximizes using his harvesting and processing technique. “We collect the fat and then centrifuge in such a way that we are left with only the most dense, stem cell-rich fat,” he explained. “The oily fat residue is either thrown out, placed back into the patient or retained for research purposes.”

As for exactly what those stem cells are doing to help achieve the impressive defect filling he’s reported, “there are lots of theories that have been published by some very well-respected scientists,” Dr. Coleman said. “What most studies have shown, and what I firmly believe is taking place, is that the stem cells promote blood vessel growth and blood flow via some type of angiogenic process. That is absolutely crucial not only for the survival of the fat graft but also wound healing.”

Dr. Coleman stressed that the outcomes he and Dr. Rubin have achieved in the injured U.S. soldiers aren’t attributable just to proper fat-graft harvesting and processing; his methods for injecting the fat are also crucial. The technique involves several steps, including the placement of miniscule amounts of fatty tissue each time the surgeon withdraws a blunt cannula that is used to inject the fat into the defect being repaired. (Dr. Coleman has published extensively on these methods, and his books, “Structural Fat Grafting” [Quality Medical Publishing, 2004], and “Fat Injection from Filling to Regeneration” [Quality Medical Publishing, 2009] are considered major references on the topic.)

He also pointed out that the results he has achieved at UPMC are mirrored in several cases from his own practice. “I’ve had cases in which large craniofacial defects were repaired using these fat-grafting methods,” Dr. Coleman said. In some of the cases, he noted, patients were missing a quarter of their faces. “They still had a rudimentary jawline, so we didn’t have to reconstruct the jaw. But they did have really remarkable defects that I was able to fill in with fat grafts, and the outcomes were very impressive and long-lasting.”

“What most studies have shown, and what I firmly believe is taking place, is that the stem cells promote blood vessel growth and blood flow via some type of angiogenic process.”

“What most studies have shown, and what I firmly believe is taking place, is that the stem cells promote blood vessel growth and blood flow via some type of angiogenic process.”

—Sydney R. Coleman, MD

More Views on Stem Cells

A rash of papers has been published in the last few years in support of Dr. Coleman’s claim that adipose-derived stem cells (ASC) have the potential to enhance angiogenesis and blood flow to the graft, promote skin rejuvenation and yield a superior cosmetic result overall.

As one paper (Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2010;42(2):124-128) coauthored by Dr. Rubin noted, “The angiogenic potential of ASCs distinguishes these cells as a highly desirable cell source for transplantation and tissue repair.”

Unfortunately, many plastic surgery practices have turned that potential into breathless marketing claims about the rejuvenating effects of stem cells. The claims have drawn the attention of the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ASAPS) and the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), which released a joint position statement in May 2011 that sought to put the brakes on the hype. According to the statement, “while stem cell therapies have the potential to be beneficial for a variety of medical applications, a substantial body of clinical data to assess plastic surgery applications still needs to be collected,” and “The marketing and promotion of stem cell procedures in aesthetic surgery is not adequately supported by clinical evidence at this time.”

Dr. Lam echoed that assessment. “Personally, I don’t think there is any evidence that stem cells are really making an impact from a fat-grafting perspective,” he said. “In fact, some of the purported benefits actually can be attributed more reliably to the estrogen and aromatase levels that are present in abdominal and thigh fat grafts. So there is a voodoo element to some of the claims I’ve seen regarding ASCs that is justifiably being challenged by [the ASAPS/ASPS statement].”

Dr. Friedman agreed that stem cell technology needs to mature before becoming a mainstay of clinical practice. One major downside that has to be overcome, he noted, is the variability in the type and extent of ASCs collected from different patients and harvest sites. Variations in the skills and experience of the surgeon doing the harvesting and processing are also a hurdle, he said.

But there have been some recent gains in solving these problems. Dr. Friedman cited, as an example, the Celution System (Cytori Therapeutics, San Diego, Calif.), which automates the extraction and separation of stem and regenerative cells from a patient’s own fat tissue to form a fat graft. The system, approved in Europe in 2010 for use in breast reconstruction and the repair of soft tissue defects, “has some real promise. This may well be the future of how we’re all going to process lipoaspirates for autologous transfer,” said Dr. Friedman.

For now, however, given present processing methods, it’s a stretch to assume that stem cells in fat transfers “are really making a critical difference in outcomes beyond providing a cell population that is more robust in surviving transplantation,” he said.

Concerns

One might think that Dr. Coleman, who believes strongly in the contributions made to clinical outcomes by stem cell content in fat grafts, might have an issue with professional societies and individual surgeons advocating a go-slow attitude with the technology. But he’s staunchly in their camp, at least when it comes to marketing claims that tout the benefits of “stem cell facelifts.”

—Samuel M. Lam, MD

“I find it unbelievably difficult to understand how some of these surgeons are now making a new claim of miraculous rejuvenation from the same fat grafts we have been injecting for twenty-five years. They’re not using a new technique or an innovative device. They’re just using the term ‘stem cell’ to market themselves as having a procedure that their competitor surgeons cannot provide, and I think that’s unconscionable.”

The debate over ASCs promises to continue, given the preliminary nature of the relevant research. As for the more practical consideration of just how extensive a facial reconstruction should be attempted with fat grafts, Dr. Coleman added this final consideration: “I use my technique of fat grafting primarily for cosmetic repairs such as restoring facial tissue that has atrophied due to aging, acne, accidents or disease. But, in select cases, it can be a very effective filler for larger defects.” In fact, he added, “it really should be considered to be the best choice for a soft tissue filler.” ENT TODAY

Leave a Reply