Explore This Issue

November 2013

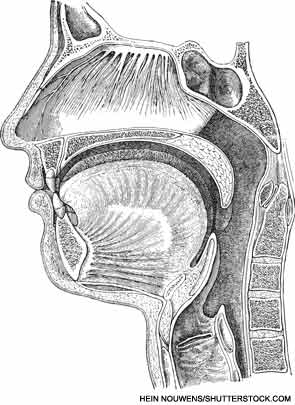

VANCOUVER—Many surgical options exist for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients, but choosing among them can be difficult. Anatomical considerations and available research studies can help guide the decision when it comes to navigating through the many palate surgery procedures, said a panel of experts here at the 2013 AAO-HNS Annual Meeting. Many of the experts who spoke during the mini-seminar on the topic actually pioneered the procedures they discussed.

“I have my own approach to selecting a palate surgery technique for a certain patient, and other surgeons ask me all the time how I make those decisions,” said moderator Eric J. Kezirian, MD, MPH, director of sleep surgery in the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California San Francisco. “I thought we should bring together the surgeons who have developed these procedures or performed research in the area to share their experiences.”

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP): This procedure, the most commonly performed procedure for sleep apnea, has been proven to show improvements in sleep study results such as the apnea-hypopnea index, mortality and quality of life, said Edward Weaver, MD, MPH, chief of sleep surgery and director of outcomes research in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Washington in Seattle. However, response rates are sometimes considered less than desirable.

Relocation pharyngoplasty: Hsueh-Yu Li, MD, chief of the department of otolaryngology at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan, developed relocation pharyngoplasty, a procedure that involves removing supratonsillar fat tissue while leaving muscle tissue intact.

Lateral pharyngoplasty: Lateral pharyngoplasty is designed to prevent lateral pharyngeal wall collapse in obstructive sleep apnea, and a primary component for patient selection is sagittal collapse during Mueller’s maneuver. The procedure has been found to improve snoring, sleepiness and apnea. Patients with markedly enlarged tonsils and positional sleep apnea do better with lateral pharyngoplasty, said Dr. Li.

In expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty, the lateral pharyngeal walls are stiffened to prevent their collapse, said Kenny Pang, MD, director and consultant at the Asia Sleep Centre in Singapore. In 2007, Dr. Pang published a randomized trial comparing the procedure with UPPP in patients with mild to moderate OSA who had undergone an examination suggesting palatal collapse without markedly enlarged tonsils (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:110-114). The success rate was 78 percent for expansion sphincter pharyngoplasty (ESP) and 46 percent for UPPP, and there was a greater improvement in the apnea-hypopnea index in the ESP group.

The lateral pharyngoplasty procedure enlarges the pharyngeal airway by cutting the superior constrictor muscle and mobilizing, dividing and relocating the palatopharyngeus muscle. The survival of the palatopharyngeus flap and preserving the soft palate and uvula to avoid velopharyngeal insufficiency are key to success in this procedure, said Michel Cahali, MD, PhD, an otorhinolaryngologist at the University of São Paolo in Brazil. When the procedure fails, it’s usually because there has been only lateral enlargement of the space, a lack of mobility or division of the palatopharyngeus or bilateral necrosis of the palatopharyngeus flap, he said.

Z-palatoplasty: Michael Friedman, MD, chairman of otolaryngology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, developed Z-palatoplasty (ZPP) as an option in patients for whom UPPP has failed. The procedure is designed to create an anterolateral direction of scar contracture that opens the airway as healing occurs. Objective success rates are much higher for ZPP than UPPP, at 68 percent and 28 percent, respectively (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:89-100).

“Since the procedure involves considerable morbidity, it should be considered only for very select patients with severe disease who are not candidates for alternative therapy,” Dr. Friedman said in his presentation. “Selected patients who proceed with the procedure are likely to have subjective and objective improvement, with a reasonable chance for ‘cure.’”

Palatal advancement: In palatal advancement, a section of the hard palate is removed to make more space at the back of the pharynx. The soft palate is then moved forward and re-attached. This enlarges the space and gives more tension to the soft palate to help avoid collapse.

Indications for the procedure are retropalatal stenosis or scarring, failure of the UPPP with persistent narrowing and proximal pharyngeal narrowing, said B. Tucker Woodson, MD, chief of the division of sleep medicine and professor of otolaryngology at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Patients are not candidates if there’s a concern about compromised palatal blood supply, if they’re are unable to tolerate an oral splint, if they have poor lateral wall movement, if they have impaired swallowing or speech or if they have maxillofacial surgery planned.

Soft-palate implants: These implants are not a good treatment for sleep apnea but can work well in snoring for patients with palate flutter and realistic expectations, said Brian Rotenberg, MD, MPH, director of the sleep surgery program at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada. The implants are contraindicated for smokers, obese patients, those with an AHI over 15, those with symptomatic OSA and a tonsil size two or greater. Studies have shown minimal improvements in AHI scores (approximately three to four points difference before and after the surgery) and extrusion rates of 2 to 4 percent. Often, there’s early improvement, followed by some clinical decline over time, so patients should be counseled about expectations.

Leave a Reply