Treatment for patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) remains challenging given the low compliance rate for continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy. Oral appliances are increasingly as a primary treatment for patients with mild to moderate sleep apnea or for patients who are unable or unwilling to tolerate the CPAP mask and machine. These uses are in accordance with the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s (AASM) 2006 practice parameters for oral appliance use (Sleep. 2006;29(2):240-243). Data show improvements in sleepiness and quality of life with these appliances, although CPAP remains superior in reducing polysomnographic indices of OSA such as reductions in apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and oxygen saturation (Intern Med J. 2010;40(2):102-106). Some evidence suggests, however, that oral appliances may confer comparable AHI and oxygen saturation to CPAP because of their compliance rates. The growing emergence of oral appliances as an alternative to CPAP has highlighted a multidisciplinary approach to treatment for sleep apnea.

Explore This Issue

December 2011“The basic issue for me is that sleep apnea is a medical disease, and although a dentist needs to be involved when using an oral appliance to maintain dental health, a physician needs to be involved in treating the airway and medical disease,” said B. Tucker Woodson, MD, professor of otolaryngology and communication sciences at Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, Wisc. “The otolaryngologist is ideally positioned because we understand the airway and we understand dental disease.”

John Remmers, MD, a pulmonologist and professor of internal medicine and physiology and biophysics at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada and one of the inventors of CPAP, said otolaryngologists may be the physicians most prone to recommending oral appliances.

“Most of us sleep physicians are pulmonologists and we are comfortable with pressures and air flows, so CPAP is very intuitive to us,” he said. “Surgeons are different and are more anatomically oriented, so it is understandable that they may be more open to oral appliances.”

Oral Appliances

According to Alan A. Lowe, DMD, PhD, there are two kinds of oral appliances: those that move the jaw forward and tongue-stabilizing devices that hold the tongue forward. The goal of both types of devices is to expand the upper airway to improve airflow, thereby preventing the collapse of the pharynx during sleep, said Dr. Lowe, chair of orthodontics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, BC.

Appliances that move the jaw forward are known as mandibular advancement devices (MADs). To date, most of the research on mandibular advancement has focused on these devices. MADs prevent the collapse of the upper airway by mechanically protruding the mandible (Intern Med J. 2010;40(2):102-106). A key issue still to be resolved, however, is the best way of titrating mandibular advancement to achieve optimal efficacy and comfort for each patient. The need for proper titration is highlighted by data that show high response rates, improvements in sleepiness and cognitive tests, and increases in health-related quality of life in patients fitted to MADs that are properly titrated (Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15(6):591-596).

“The problem with MADs is that the dentist doesn’t always know who will respond to MADs or exactly how much protrusion is needed for effective therapy,” Dr. Remmers said. He added that the adjustments or titrations that are done to get a positive response are often highly subjective and rely less on precision than guesswork. “This all leads to the difficulty for the physician in both selecting patients for MADs and providing a recommendation on how much to adjust the oral appliance to achieve efficacy,” he said.

Tongue-stabilizing devices (TSDs) are not as well studied or used. However, results of a recent randomized study that compared TSDs to MAS (mandibular advancement splint) suggest that MAS may remain the preferred device for now based on lower tolerance associated with TSDs despite comparable efficacy (Sleep. 2009;32(5):648-653).

“In clinical practice, the use of MAS is likely to predominate,” said Peter Cistulli, MD, head of sleep medicine at the University of Sydney’s Sydney Medical School in Australia. He added, however, that the development of more tolerable methods of advancing the tongue may be warranted given a recent study he and his colleagues conducted that found that the magnitude of upper airway enlargement was greater with TSD than with MAS (Sleep. 2011;34(4):469-477).

Efficacy of MADs

Several studies have shown the efficacy of MADs for improving snoring, reducing excessive daytime sleepiness, effecting some improvements in neuropsychological functioning and modestly reducing blood pressure in patients with OSA (Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;16(6):591-596). Most data show that the effect of these devices on AHI and oxygen saturation is lower than the effect seen with CPAP, but the better compliance seen with oral devices may result in comparable outcomes between these two modes of treatment.

Dr. Lowe emphasized the importance of educating otolaryngologists about the usefulness of oral appliances and their feasibility as another adjunct to OSA treatment. “The advantage of an oral appliance is that it is worn more but may be less effective for oxygenation. The advantage of CPAP is that it is worn less but is more effective for oxygenation,” he said. “What really matters is how the quality of life for the patient has changed, and this outcome is pretty comparable between oral devices and CPAP.”

Patient Selection

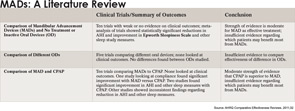

One overall limitation of the studies on MADs to date has been the quality of the evidence used to make treatment decisions, which, according to a 2011 review of the literature commissioned by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), is only moderate to insufficient (AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. 2011;32).

This review emphasizes the critical question facing otolaryngologists trying to decide whether or not to use an oral appliance: how to identify which patients will benefit the most from these devices.

Dr. Remmers said the prediction capability regarding which patients will respond to oral appliances is still lacking. Most physicians, he said, will only consider an oral appliance for patients who have a respiratory disturbance index of <20, are not obese, have failed CPAP and have an adequate dentition. “However, research on MADs has shown that many patients who fall outside of these criteria can be well treated with oral appliances,” he said.

To date, research on patient selection for MADs has involved looking at anatomical problems, such as structural narrowing of the pharynx, which may identify patients who may not be good candidates for an oral appliance. Other data suggest that the use of nasopharyngoscopy may help identify which patients will respond to MADs. One study found an association between a reduction in AHI in patients who showed improvement in upper airway patency with mandibular advancement during a drug-induced sleep nasopharyngoscopy (Eur J Orthod. 2005;27(6):607-614). In addition, evidence suggests that performing a nasopharyngoscopy when a patient is awake may be useful in predicting treatment response to MADs (Eur Respir J. 2010;35(4):836-42).

Other studies are looking at whether removing the obstruction in the airway of a patient by protruding the mandible during sleep may identify a patient as a good candidate for a MAD. According to Dr. Remmers, who is studying this approach, two published studies (Eur Respir J. 2006;27(5):1003-1009; Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(4):366-370) and data from a recent unpublished study of 65 patients now show unequivocally that patients can be identified in a sleep study using a device in which the protrusion is progressively titrated, similar to CPAP titration, until the obstruction is removed. “The nice feature with this approach is that if you do eliminate the obstruction, you not only know that patient will respond to MADs but you know exactly how far the mandible needs to be protruded to achieve this,” he said. The research in this area is expected to be embodied in a new MAD titration product known as MATRx, due in early 2012.

Issues to Consider

Along with identifying patients for whom oral appliances may work best, other issues that may need consideration include the major side effect of these appliances, tooth movement or occlusal changes.

Dr. Lowe considers this a small disadvantage compared to the benefit of controlled OSA. “The longer we are in the field, the more we are accepting that [tooth movement] as a side effect and we work around it because compared to decreased oxygen to the heart, it is a pretty minor thing,” he said.

Finally, an important role for oral appliances may be in their use in conjunction with CPAP. “CPAP and oral appliances can be used interchangeably,” said Fernanda Ribeiro de Almeida, DDS, PhD, assistant professor of dentistry at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, BC, Canada. She said many patients who use CPAP routinely may be more compliant overall with treatment if they use oral appliances when CPAP is less convenient, such as on the weekends or when travelling.

Disclosures: Dr. Cistulli has contributed to the development of the mandibular advancement splint. He has also consulted for and has been on the advisory board for oral device maker SomnoMed and has financial interest in the company. Dr. Remmers receives royalties from AutoCPAP and is part owner of Zephyr, the company that manufactures MATRx a test for selecting patients for oral appliance therapy. Drs. Fernanda and Tucker report no relevant financial ties.

Leave a Reply