In mid-February, the Joint Commission introduced a new online tool meant to help combat inconsistencies in the surgical time out process.

Explore This Issue

March 2012To access the tool, health care providers must log in to the Targeted Solutions Tool (TST) website (jointcommissionconnect.org), where they can review a list of events that should occur before an incision is made. The aim is to prevent a cascade of errors that can begin before a patient is wheeled into the operating room.

Project Leader Melody Dickerson, RN, MSN, said the tool is meant to help organizations measure risk across their surgical system, including scheduling, pre-operative and operating room areas. The tool assists in monitoring surgical cases for weaknesses that could result in wrong-site surgeries, she said. “Most organizations are really proud of their OR on-time start records,” she said. “Yet most don’t have a policy in place to ensure that the necessary documentation is available when the patient arrives for surgery.”

Since the Joint Commission released its Universal Protocol regarding this issue in 2004, hospitals have made refinements to their time outs in order to reduce the incidence of wrong-site, wrong-procedure and wrong-person surgery.

Variation

Hospitals, ambulatory surgical centers and health systems are tailoring time outs to their specific needs, and otolaryngologists in various subspecialties must conform to these regulations.

“Most surgeons working in hospitals really don’t have a choice as to how they do time outs. It typically is an OR or hospital standard,” said Michael M. Johns III, MD, associate professor of otolaryngology at Emory University School of Medicine and director of the Emory Voice Center in Atlanta.

In formulating these policies, however, hospital administrators do seek input from surgeons, anesthesiologists and nurses. While this sets a minimum standard, health providers can go above and beyond the basics to ensure safety.

“I think it’s important, as part of the time out, not to just review who the patient is, what the surgery is, what the planned procedure is, but also to make sure that all the critical equipment that’s needed for the case is functioning before you start,” Dr. Johns said.

Ideally, the dialogue should cover anticipated blood loss and other complications. “If you review those additional things beforehand,” he said, “then you’re less likely to have errors. It doesn’t take a lot of time to do this. It really is a one-minute-or-less procedure.”

Time outs are typically done with the surgeon and the circulating nurse confirming the patient’s name, side of the surgery, exact procedure and proper body positioning. The scrub nurse, scrub technician and anesthesiologist are also included. If they do not agree on all these pieces of information, the process is halted until resolution occurs.

“From a personal standpoint, I have always reviewed the chart immediately before surgery to be certain the correct procedure and side is being done, in addition to the time out,” said Gerard J. Gianoli, MD, FACS, clinical associate professor of pediatrics and associate professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans and president of the Ear and Balance Institute in Baton Rouge, La. “The bigger difference is not specialty related but institution related. Each hospital or surgery center does it a little differently. Some require placing your initials on the operative side in the holding area before going to the OR, while the patient is alert and has input. This is probably better than the time outs we do in the OR.”

Whether a surgeon or nurse initiates a time out depends on each hospital, surgical center or health system. Everything is generally done the same way each time, and all surgical team members must be physically and mentally present, said Nwanmegha Young, MD, assistant professor of surgery and otolaryngology at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn. “A nurse initiates it, but everybody participates,” Dr. Young said of Yale’s standard protocol. All other actions and conversations cease. “Everybody must face the patient during the time out, and everyone introduces themselves by name and role,” he said.

The exchange among Yale’s surgical team follows this fashion: First, a circulating nurse reads aloud the information on a patient’s armband. The surgeon then states the procedure and the side on which it will be performed. The circulating nurse reads from the consent form to confirm that it matches the surgeon’s description. In addition, the nurse notes the X-ray images, special equipment and supplies on hand. The anesthesiologist goes over allergies and antibiotics, and then the surgeon indicates whether the case will be routine or if any unusual challenges are expected.

“There’s a lot of redundancy in our time outs to make sure that everything has been double-checked or triple-checked,” Dr. Young said.

Aspects of the time out also may differ based on the organ involved in a procedure. “Obviously, right ear versus left ear is very important,” said Dean M. Toriumi, MD, FACS, professor in the division of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery, department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery, at the University of Illinois at Chicago. About 70 percent of Dr. Toriumi’s practice is devoted to rhinoplasty, so the potential for operating on the wrong side is obviously limited, he said.

For endoscopic sinus surgery, however, confirming the correct side is crucial during the time out. More than 250,000 of these surgeries are performed annually in the U.S. (Laryngoscope. 2012.122(1):137-139). “Although overall complication rates are low,” the authors wrote, “errors can lead to significant morbidity due to the close proximity of the sinuses to the orbit and skull base and the resultant potential for blindness, cerebrospinal fluid leak, and catastrophic bleeding.”

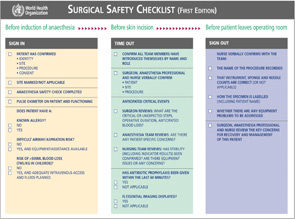

To limit preventable adverse events, most operating rooms have adopted surgical checklists endorsed by the World Health Organization (see “Surgical Safety Checklist,”). The WHO Safe Surgery Checklist identifies three phases of an operation: before the induction of anesthesia (“sign in”), before the incision of the skin (“time out”) and before the patient leaves the operating room (“sign out”). A checklist coordinator must confirm completion of the listed tasks in each phase before the team is permitted to continue. However, standardized surgical checklists, designed for general or orthopedic procedures, often do not address specifics related to endoscopic sinus surgery.

A surgeon in this subspecialty directs supplemental items during the time out. “First, the surgeon informs the team that a topical vasoconstricting agent will be used (often high-dose epinephrine, cocaine or oxymetazoline), and that this agent has been stained (usually fluorescein or marking ink), is labeled appropriately and is not to be used for injection,” the authors explained in Laryngoscope. “This step is critical, as injection of these potent agents is a genuine risk and can precipitate hypertension, arrhythmia, and even stroke, myocardial infarction, or death.”

Effectiveness

While it’s difficult to quantify how much the time out has lowered the incidence of wrong-site surgery, the process has certainly helped, said Rahul K. Shah, MD, associate surgeon-in-chief at George Washington University School of Medicine and Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C. Any distraction interferes with the intense focus of an ideal time out. “If it gets interrupted, start over; or if there is any ambiguity, start over,” he said.

A recent study, led by Dr. Shah, revealed substantial variation in the time out and site-marking procedures within pediatric otolaryngology. The survey was e-mailed via the American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology (ASPO). Researchers asked 167 Child Health Corporation of America hospital operating room directors and ASPO members about peri-operative preparation of their patients (Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(1):69-73).

Most respondents performing surgeries at children’s hospitals reported that the policies do not mandate site marking for bilateral placement of ventilation tubes, adenotonsillar surgery, airway endoscopy or nasal surgery. Policies allowing assistants to perform site marking were identified by 45 percent of respondents from children’s hospitals.

Community hospitals were 3.68 times (range, 1.31-10.31 times) more likely than other facilities to permit site marking performed only by the attending. Most respondents operating at children’s hospitals (84.4 percent) were satisfied with their hospital’s site-marking and surgical checklist policies for pediatric otolaryngology procedures (87.1 percent). Twenty-one percent of survey respondents reported involvement in a wrong-site surgery at some point in their careers.

“There is a dynamic tension between universal, national mandates and allowing local variation to encourage hospitals to tailor policies to unique needs,” the authors concluded. “Further study is needed to determine if the observed variations are beneficial or harmful.”

Best Practices

Dr. Shah said it helps to have surgeon champions who are proactive in implementing the safety goals set forth in the Joint Commission’s Universal Protocol. “The more champions you have advocating” for the protocol, the more robust the time out process, he said.

Making the time out routine in every case “significantly adds to the safety of the operating room,” said David J. Arnold, MD, FACS, associate professor of head and neck surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. “We’ve changed our culture so that it is part of the whole experience. It’s what’s expected.”

In many hospitals, nurse-initiated time outs can help level the hierarchy and encourage surgical team members to speak up if something does not look or sound right, said Michael G. Glenn, MD, FACS, medical director and physician-in-chief at Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle, where he practices otolaryngology. By fostering an atmosphere in which members feel comfortable introducing themselves, “it gets everybody on a first-name basis, [and] we believe that helps create a culture where people are less afraid to raise important questions or concerns,” he said.

While use of the time out has decreased the number of errors, its effectiveness is compromised when only part of the surgical team participates. The timing of this event is also crucial to catching potential mistakes, and it should not occur after induction, prepping and incision, according to the American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities (AAAASF). “What is included and excluded in the verbal report has also been shown to be critical, as is whether the surgeon, as the leader of the team, gives the report or it is done by others on the staff,” wrote Phil Haeck, MD, the AAAASF’s former vice president of legislation, in the summer 2009 issue of The ASF Source, the association’s newsletter. “The real problem lies in the possibility that as this becomes mundane and repetitive, participants can shut out the verbiage, become inattentive and lose the real value of the work stoppage. Error rates have crept back up in some institutions, especially when the technique is not rigidly adhered to.”

Retracing a team’s steps helps understand what led to confusion. “In many of these instances, the consent form matched the surgical schedule and the entire team remained convinced they were correct,” Dr. Haeck continued. “What produced this misperception was the dictation at the original examination where the surgeon, busy or distracted, left the consultation room and produced paperwork or a scheduling form with the wrong site included. The no-brainer here is that in each of these instances, no one asked the patient.”

A New Tool

Health care professionals and patients concur that wrong-site surgery should never happen. While most states do not require facilities to report these adverse events, some estimates from the Joint Commission suggest that the national incidence rate of wrong-patient, wrong-procedure, wrong-site and wrong-side surgeries may be as high as 40 per week. Viewing this as a major threat to patient safety, eight U.S. hospitals and ambulatory surgical centers collaborated with the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare (CTH).

The wrong-site surgery solutions provided by the TST are the culmination of work started in July 2009 by CTH and the Lifespan health system in Rhode Island. Their goal was to improve safeguards designed to prevent wrong-site, wrong-side, wrong-procedure and wrong-patient surgical procedures. In 2010, four additional hospitals and three ambulatory surgical centers joined the project.

Among the problems uncovered was the fact that a time out without complete participation by all key people in the operating room contributed to the risk of wrong-site surgery. Issues with scheduling and pre-op/holding processes, as well as ineffective communication and distractions in the operating room, also heightened the risk. Addressing problems with documentation and verification in the pre-op/holding areas reduced defective cases from a baseline of 52 percent to 19 percent. Defects are the causes of and risks for wrong-site surgery. As a result, the incidence of cases with more than one defect dropped 72 percent.

The original participating organizations used Robust Process Improvement (RPI) to identify targeted solutions. RPI is a fact-based, systematic and data-driven problem-solving methodology that incorporates tools and concepts from Lean Six Sigma and change management methodologies. Project teams measure the magnitude of the problem (in the case of wrong-site surgery, specific issues that increase the risk of this event) and pinpoint the contributing causes, developing particular solutions targeted to each cause and thoroughly testing them in real-life situations.

Those participating in CTH’s project identified 29 main causes of wrong-site surgeries that stemmed from the organizational culture or that occurred during scheduling, in pre-op/holding or in the operating room. During the project, the original eight project organizations decreased the number of surgical cases with risks by 46 percent in the scheduling area, 63 percent in pre-op and 51 percent in the operating room. Hospitals and ambulatory surgical centers pilot-testing the TST experienced the same gains as the original participants.

The Joint Commission’s TST aims for even greater consistency. “There should be one way to mark a site, not seven different ways to mark a site,” said Dickerson. While the TST does not make requirements, the Universal Protocol outlines times when a site mark is appropriate. What the TST does is help an organization measure whether or not a mark is being applied as expected, including the type of mark and its proximity to the incision site, as well as whether team members reference the site mark during the time out.

By inputting their own data, health care providers can identify areas of weakness and implement custom-designed solutions to reduce these risks. “What this project does,” Dickerson added, “is pull the covers back to really see what’s going on in their surgical processes.”

Leave a Reply