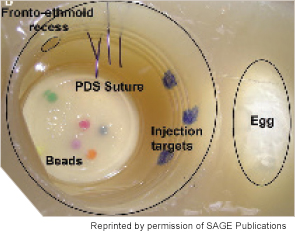

Labeled sinonasal cavity of fully constructed sinus surgery task trainer (left).

Medical simulation, whether it comes in the form of high-tech machines, dummies that act like real patients, or even homemade concoctions made to look like the tympanic membrane, is increasingly a part of the training experience of medical students and residents. In a 2011 survey conducted by the American Association of Medical Colleges, 83 of the 90 medical schools that responded indicated some use of simulation across a five-year span of residency education, and 55 of the 64 teaching hospitals that responded indicated use of simulation.

Explore This Issue

October 2014No figures exist on exactly how many otolaryngology programs are using simulation, but the scientific literature is full of descriptions of simulators that are currently available or under development. One systematic review, for example, describes 13 bronchoscopy simulators, 10 sinus/rhinology simulators, eight oral cavity simulators, eight neck simulators, and even simulators that teach nontechnical skills like teamwork (Int J Surg. 2014;12(2):87-94).

Educators encourage the trend, saying that medical simulation is a way to help residents warm up to working with real-life patients.

“It’s not going to replace actual patients, because eventually you have to finesse your skills with real experiences, but it can help you accelerate the learning curve and do that without direct risk to real patients,” said Ellen Deutsch, MD, FACS, FAAP, director of surgical and peri-operative simulation at the Center for Simulation, Advanced Education, and Innovation at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Deutsch is also chair of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Surgical Simulation Task Force.

Plus, residents love it. “Especially for the junior residents, it gives them a sense of accomplishment to be able to master these techniques in the lab. They feel more confident and less anxious when they get into the operating room,” said Sonya Malekzadeh, MD, FACS, professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, DC.

Simulation can also extend the teaching of important clinical skills that are sometimes limited because of ACGME work-hour restrictions, said Marvin Fried, MD, chairman of otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore Medical Center in New York, where he’s been working with medical simulation for the past 14 years. “[Residents] feel they learn more from the simulation environment than they do observing or trying to learn from a textbook. It’s more real.”

Most importantly, exposing your students to simulation doesn’t mean overhauling your education program. Here are tips on how to get started:

Perform a cost-benefit analysis: Before asking your institution to spend thousands of dollars on a simulation device, do some research. The cost of simulators can vary significantly, Dr. Deutsch said, but even some of the high-tech simulators are about half as expensive as an operating microscope. “You have to keep the cost in proportion with what you’re accomplishing,” she said. “If you’re improving patient outcomes and decreasing the risk of patient complications, that cost is an investment.”

Also, creating a successful simulation program requires more than just investing in a simulator, Dr. Deutsch said. “The educator needs to have, or be able to assemble, content expertise and simulation knowledge as well as a simulator,” she said. “The simulator itself could be a simple gadget, a sophisticated construction, equipment with a virtual (computer) interface, a high-technology human replica, animal tissue, or even a person trained to act as a patient, a family member, or another healthcare provider.

Sign up for existing programs: Rather than reinvent the wheel, you could attend or send residents to the numerous simulation boot camps that are held throughout the year around the country, said Kelly Michele Malloy, MD, clinical assistant professor of otolaryngology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Dr. Malloy collaborated with Drs. Deutsch and Malekzadeh to create the original Otorhinolaryngology (ORL) Emergencies Boot Camp in 2010 in Washington, DC. The program, now in its fifth year, uses simulators to teach skills ranging from endoscopy and emergency airway management to control of epistaxis and drainage of peritonsillar abscess. The participants then work through various clinical scenarios using high-tech manikins that mimic, for example, a patient with an airway or post-surgical concern.

Dr. Malloy said the DC course is directed at the new PGY2 resident, but other courses have been developed for other target learner groups. One of these includes ORL SimFest, a course held annually at the University of Pennsylvania that uses simulation to teach PGY3 residents more advanced surgical skills such as microlaryngeal surgery, local flap design, and temporal bone surgery. Course fees for these programs are kept low to remain affordable for residency programs—between $150 and $240 for each day-long intensive course, she said.

“The best way to learn about simulation is to see it from people who are already using it,” Dr. Malloy said. “Then you are equipped to implement simulation in your home institution, as well as develop new ideas for future simulators.”

Here are some programs:

ORL Boot Camp

Medstar Georgetown University Hospital

Washington, DC

orlbootcamp.sitel.org

ORL SimFest

Philadelphia, Pa.

uphs.upenn.edu

ORL Essentials Boot Camp

University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

orlessentialsbootcamp.com

Annual Neonatology Boot Camp

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

chop.edu

Emergencies in Otolaryngology Bootcamp

London Health Sciences Centre

London, Ontario, Canada

lhsc.on.ca

Find out what’s already available in your institution: One easy way to get started with simulation is to find out what simulation devices and programs are already available at your medical school or hospital. As Dr. Fried explains, at many hospitals, simulation is part of the required training program for anesthesiology residents. Otolaryngology residents could share use of the devices that teach residents how to intubate patients.

“Anesthesiologists are probably the most advanced specialty in terms of simulation. They’ve been doing this for 15-20 years at a very sophisticated level,” he said.

It would also be worth asking around to see if any programs are doing simulations in bronchoscopy, esophagoscopy, or pulmonary and gastrointestinal, he said. You may be surprised by what you never knew was available. “I think if the hospitals that I know of are similar to those in most of the country, there is no sharing of information,” he said.

Join clinical trials: Another inexpensive way to get involved in simulation is to join a clinical trial. Several multicenter trials are underway that aim to demonstrate the efficacy of simulation programs, said Gregory J. Wiet, MD, professor of otolaryngology, pediatrics, and biomedical informatics and program director of the pediatric otolaryngology fellowship at The Ohio State University College of Medicine in Columbus. Dr. Wiet, who is also a member of the AAO-HNS surgical simulation task force, said one of the objectives of the task force is to provide a way for institutions to test the validity and efficacy of simulators that have already been developed. Task force members are currently trying to acquire information on programs being developed and plan to eventually post this information on the academy’s website. The information will make it easier for researchers looking to do multicenter trials. These clinical trials will also eventually be posted on the website.

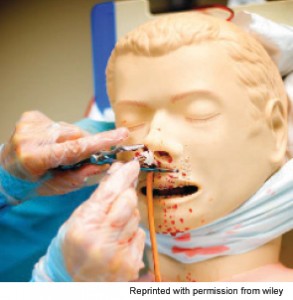

Epistaxis skill station.

Start small: It can be easy to be overwhelmed by the number of simulation options out there. Do you invest in a pricey temporal bone simulator? Change your curriculum? Send all of your residents to ORL boot camps? Dr. Malekzadeh advises focusing on one educational target at a time. “Simulation can seem daunting, as it often requires resources such as space, time, and money. But by focusing on specific procedures residents are struggling with, one can creatively develop simulators to teach the necessary skills,” she said.

Approximately seven years ago, Dr. Malekzadeh did just this, when she noticed that her junior residents were having trouble mastering sinus procedures. She started reading about what her general surgery colleagues were doing with box trainers to teach their residents surgical techniques before going into the OR. “I thought that was genius, so I collaborated with our simulation center and nurse educator to develop a low-cost sinus trainer,” she said. The result? Her residents became much more skilled and proficient at sinus surgery once the time came to work with real patients.

Make your own learning tools: Another thing to keep in mind: Simulation tools don’t have to be high tech. In fact, many of the training tools that Dr.

Malekzadeh uses she first made and tested in her own kitchen. For less than five dollars, for example, Dr. Malekzadeh created an endoscopic sinus surgery task trainer. In this paper, she described the final version of the training device that she perfected with a team of otolaryngologists and simulation center staff:

The model is prepared using a ballistics gel substrate by mixing 1 pound of Knox gelatin powder with 1 gallon of water. Once thoroughly saturated, the gel is warmed to 130°F using a double boiler. A 10 × 24 × 6-cm stainless steel bread pan serves as the gelatin mold. Two 100-mL cups are placed upside down in the pan and stabilized with a weight to prevent capsizing, forming the right and left sinonasal cavities. A 2-cm layer of warm gel is poured into the mold and allowed to cool for two hours.

Once solid, two eggs, representing the maxillary sinuses, are placed adjacent to each of the medicine cups. Six beads of varying colors, placed on the base of each cup, are held in place with a small amount of room temperature gel. A second layer of room temperature gel is poured in the bread pan until the cups are completely submerged.

The model is refrigerated for eight hours to allow solidification. The mold is delivered from the pan, and the cups are carefully removed. Four 1-inch strands of expired 1-0 PDS suture are inserted into the superior quadrant of the gel. An expired 8-mm dermal biopsy punch creates an opening in the superior medial aspect of each sinonasal cavity. Last, three target lesions are drawn on the lateral aspect of each nasal cavity using a permanent marker. A silicone CPR manikin mask, placed over the trainer, creates a life-like model, allowing learners to perform through correct anatomic features (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:530-533).

“The goal is to develop familiarity and possibly proficiency, not expertise,” she said. “We’re just helping residents become more comfortable with the steps of the procedures and function of equipment before working with patients.”

Stephanie Mackiewicz is a freelance medical writer based in California.

Leave a Reply