Since the 1980s, physicians who treat a subset of head and neck cancer patients have seen an increasing number of patients who don’t fit the typical profile seen prior to this time. Instead of older men with a history of hard drinking and smoking, there has been a steady increase in the incidence of oropharyngeal cancers in younger patients—younger white men in particular—with little or no history of drinking or smoking.

Explore This Issue

November 2012What has emerged over the past 15 years is a distinct subgroup of head and neck cancers caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV), according to Edward S. Peters, DMD, associate professor of epidemiology at the School of Public Health at Louisiana State University’s Health Sciences Center in New Orleans. He emphasized the need to recognize the changing profile of patients in this subgroup of head and neck cancers. “We should be more astute and vigilant in examining, for example, young patients with complaints of soreness in their throat or on the back of their tongue for possible lesions,” he said.

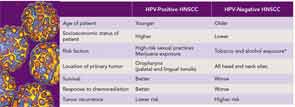

Dr. Peters and his colleagues found recent evidence of the increased incidence of HPV-associated head and neck cancers and the changing profile of these patients in a study published earlier this year that looked at the incidence of HPV-associated head and neck cancers by age and ethnicity in the United States from 1995 to 2005 (PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e32657). The study found that although non HPV-associated head and neck cancers significantly declined during this time, there was a significant increase in HPV-associated head and neck cancers, with the greatest increase in white males between 45 and 54 years of age.

Other epidemiological data confirm this. The most recent report, published in August, found that up to 80 percent of oropharyngeal cancers are now caused by HPV and that these cancers are more likely, when compared with non-HPV-related head and neck cancers, to occur in whites (93 percent versus 82 percent in non-whites), never drinker/never smokers (16 percent versus 7 percent), those with a younger median age at cancer diagnosis (54 versus 60 years), and patients who have had more than six oral sexual partners over a lifetime (46 percent versus 20 percent) (Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2012;45:739-764).

History of Oral HPV

Although the increased incidence of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer is now well established, the actual number of people with HPV infection who will develop oropharyngeal cancers is quite small based on what is known about the natural history of HPV infection in anogenital cancers. “Most people will have a genital infection in their lifetime,” said Gypsyamber D’Souza, PhD, assistant professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. “Most people get infected within a few years of becoming sexually active, and most people clear those infections within a year of being infected,” she said.

More than 100 subtypes of HPV have been identified since the discovery that HPV causes cervical cancer, with specific types considered high risk as causative agents of cancer. Unlike cervical cancer, in which two types of HPV strains cause most anogenital cancers (HPV-16 and HPV-18), HPV-16 accounts for more than 90 percent of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers. It is thought that HPV disrupts the cell cycle and, for people who do not clear the infection, malignancy can occur when the tumor suppressor protein p53 and the retinoblastoma protein (pRb) are inactivated by the expression of viral E6 and E7 oncoproteins.

“We think there is a long latency for progression of oral HPV infection into HPV-related head and neck cancers.”

“We think there is a long latency for progression of oral HPV infection into HPV-related head and neck cancers.”—Gypsyamber D’Souza, PhD

Although Dr. D’Souza said that the natural history of oral HPV is not well studied, she said the data suggest that it is similar to cervical cancer. For the minority of people who do not clear HPV infection on their own, the risk of developing disease increases the longer HPV persists.

“This is a very long process, and in the cervix it takes over 10 years from the time of infection to the development of malignancy,” she said. “We think there is likely a similar long latency for progression of oral HPV infection into HPV-related head and neck cancers.”

Unlike cervical cancer, however, there are no tests comparable to a Pap test to detect precancerous lesions in the oropharynx. “We don’t have a good screening option,” said Erich M. Sturgis, MD, MPH, professor in the department of head and neck surgery at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. He added that the entire mucosal surface of the cervix is easier to examine than that of the tonsils and base of tongue, the two sites predominately affected by HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers.

One ongoing challenge is to find a standard way to detect HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers to help tailor treatment for these patients (see “Tests Emerging as Standards for Diagnosing HPV-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer,” p. 26). The importance of finding such a method is highlighted by studies that consistently show better survival in patients with HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers than those with non HPV-related cancers.

Survival Benefit in HPV-Related Oropharyngeal Cancers

A recent 2012 meta-analysis that pooled data from 42 studies found significant improvement in both progression-free survival and disease-free survival in patients with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers when compared with HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancers (Oral Oncol. [Published online ahead of print July 27, 2012.]). A similar benefit was seen in a retrospective analysis of patients with stage III or IV oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma enrolled in a randomized trial that compared survival outcomes of patients treated with accelerated-fractionation radiotherapy and those treated with standard-fractionation radiotherapy combined with cisplatin therapy. A total of 206 of 323 (63.8 percent) of patients had HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers. After adjusting for age, race, tumor and nodal status, tobacco exposure and treatment assignment, the HPV-positive patients had significantly better three-year overall survival rates compared with the HPV-negative patients (82.4 percent versus 57.1 percent, p<0.001) (N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):24-35).

According to Dr. Sturgis, patients with HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers probably do better because they have fewer genetic mutations in their cancers, versus the many mutations found in HPV-negative cancers, the majority of which are related to smoking. “In smoking-related cancers, the tumor cells have many genetic changes that may provide for many options for aggressiveness and resistance to therapy,” he said, whereas radiotherapy and chemotherapy are probably more effective in killing cells with fewer mutations, as in HPV-related cancer.

Despite the significant improvement in survival outcomes seen in patients with HPV-positive cancers, HPV status is still not used to determine treatment and is not included in the current staging system for these cancers. “It is a real problem using the current staging system to provide patients [with] accurate estimates of their survival chances, most likely because HPV is not included in the system,” said Dr. Sturgis. “We are hopeful that the future system will incorporate HPV status and the current clinical trials for patients with HPV-related cancers will allow us, in the future, to make better treatment decisions.”

Clinical trials currently underway to evaluate whether using less aggressive treatment for HPV-positive cancers can effectively treat the disease while incurring fewer side effects may change this. “I think we’re right on the verge, in the next five to 10 years, of individualizing treatment based on HPV status,” said Dr. Sturgis.

Leave a Reply