Part one of a three-part series exploring issues affecting the otolaryngology workforce.

Explore This Issue

January 2010How do you plan to deal with workforce shortages? If you are like 55 percent of the audience at an interactive mini-seminar held during the October American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) Foundation annual meeting, you intend to hire additional otolaryngologists to help with practice overload.

Current projections do not bode well for that strategy, according to workforce experts. “Those of you who want to add an otolaryngologist to your practice are guaranteed not to find one,” said Richard A. Cooper, MD, professor of general internal medicine and senior fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia. “There is a looming doctor shortage that will change the way we practice. You’re going to have to solve your practice problems another way.”

Examining alternative solutions was one major initiative of David W. Kennedy, MD, rhinology professor with the Department of Otorhinolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery, at the University of Pennsylvania Health System, during his 2008-2009 AAO-HNS presidency. He also organized the AAO-HNS mini-seminar “Physician Workforce in OHNS: What’s in Your Future?” ENT Today recently spoke with the panelists and others about possible fixes for the shortage.

Why the Gap?

In the mid-1990s, U.S. policy makers maintained that the nation was facing a physician surplus—and that this would drive up health care spending. Congress, backed up by a “Consensus Statement” endorsed by the American Medical Association and other major medical organizations, opted to freeze graduate medical education (GME) funding. The policy became law when it was written into the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.

Several experts, including Dr. Cooper and Harold C. Pillsbury, MD, Thomas J. Dark Distinguished Professor of Otolaryngology and chair of the Department of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine in Chapel Hill, have reached different conclusions after reexamining the physician workforce projections on which the Balanced Budget Act was based.

In 1995, explained Dr. Pillsbury, the managed care industry deemed necessary a target ratio of between 1.8 and 3 otolaryngologists per 100,000 to hold down costs. In 2000, he reassessed 1995 physician workforce statistics from the Bureau of Health Professions (BHP) and found that the ratio of otolaryngologists per 100,000 in 1995 was 2.962, not 3.240 as BHP statistics held. The reason: BHP had included residents in their original estimates. Because the effective numbers of practicing otolaryngologists were lower at the time GME funding was frozen, the profession is now already at the point (2.5/100,000) projected by managed care for 2020.

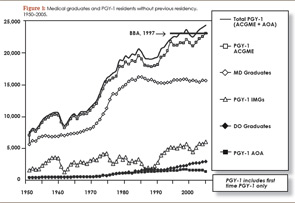

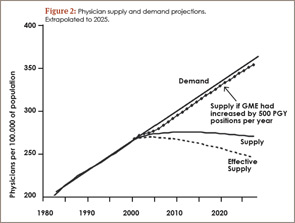

Freezing GME funding at 1996 levels has created a shortage that will be exacerbated as patient demand increases over the next 20 years. Even if 1,000 PGY-1 positions were added annually, the supply-demand gap would persist at least until the year 2050, according to Dr. Cooper [see Figures 1 and 2].

Bring in Mid-Level Providers

Many practices are already hiring physician extenders, primarily nurse practitioners (NP) and physician assistants (PA), who provide general otolaryngologic care in a team-based approach. Dr. Pillsbury warned, however, that current training for ENT NPs and PAs is inadequate, and otolaryngologists who hire physician extenders could be exposing themselves to increased malpractice risk. He and Dr. Kennedy agree that otolaryngologists should take an active role in developing an accredited, university- or AAO-HNS-based certification program for mid-level ENT providers. Dr. Pillsbury sees grants as a possible funding solution.

Telemedicine provided a way to “increase the availability of care in a situation where we would have had to either turn people away or to create wait environments that would have been clinically unacceptable.”

Telemedicine provided a way to “increase the availability of care in a situation where we would have had to either turn people away or to create wait environments that would have been clinically unacceptable.”—Moises A. Arriaga, MD, MBA, FACS

Revamp Training Programs

Dr. Kennedy believes another solution might be to institute a three-year residency in head and neck medicine, with training in minor surgical procedures, followed by an optional two-year subspecialization. The advantage of this model, similar to one used in Germany, is that those providing primary or secondary otolaryngology care would refer within the specialty for more complicated services.

Some otolaryngologists resist this idea, however. The audience responders at AAO-HNS’s mini-seminar felt that such a move might further fragment the specialty. Dr. Pillsbury sees other problems with reducing the training program. “Funding for training is available for five years or until first certification—and if first certification is only three years, you will have a hard time finding funding for an additional two-year fellowship,” he said.

Develop Telemedicine

In the aftermath of Katrina, neuro-otologist Moises A. Arriaga, MD, MBA, FACS, director of otology-neurotology and professor of otolaryngology and neurosurgery at Louisiana State University in New Orleans, and his colleagues found solutions he believes may be relevant to the impending manpower “storm.”

To maintain their residency program and continue care delivery to outlying areas, his department developed a telemedicine otology program in affiliation with their hospital’s tele-ICU program. With an onsite mid-level provider who manipulated instruments to conduct exams, the program delivered diagnostic services to patients in Baton Rouge for a year. Dr. Arriaga used special teleconference software, a video endoscope, and infra-red video goggles to remotely conduct video endoscopic ear evaluations, cranial nerve examinations, and vestibular assessments. He used Microsoft Word to augment communication with profoundly hearing-impaired patients, who could see his typed communications on a big screen.

Most patients embraced this viable delivery method, said Dr. Arriaga, but there were a few barriers. For example, the scope clouded in patients with moist ears, and some patients resisted remote care delivery. But overall, Dr. Arriaga said, telemedicine provided a way to “increase the availability of care in a situation where we would have had to either turn people away or to create wait environments that would have been clinically unacceptable.”

Going Forward

Dr. Cooper believes that all physicians should engage in public policy debates and work to increase GME funding. It might also be helpful, he said, for specialists to speak as a bloc, rather than as separate entities, when working with Congress and other policymakers.

Steven B. Levine, MD, who practices at ENT and Allergy Associates, LLC, in Trumbull, Conn., agrees with this notion. As legislative chair and president-elect of the Connecticut ENT Society, he said, “Banding together with our brethren in ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, and anesthesiology, among others, has helped us gain a better voice in our legislative process at the state level.”

Dr. Kennedy plans to take over as chair of the AAO’s Physician Workforce Committee. In the next three years, he said, “we will be getting some of the brightest minds together within the specialty to start thinking in a proactive fashion about the direction we want to take. One thing we can guarantee is that our practice will not stay the same. We don’t want to mortgage the future of our specialty by ignoring change.”

Dr. Levine, who is also a member of the AAO-HNS Board of Governors, applauds these discussions at both the leadership and membership levels but takes a bit of an optimist’s view on the issue of physician shortages. The shift in the supply and demand curve, which will reduce physician supply relative to patient demand, may not be an entirely bad thing, he posits. “It might be a mistake to try to avoid that shift, or to blunt it. It might be in our best interests, actually, to let market forces prevail!” ENTtoday

Gretchen Henkel is a medical writer based in California.

TOP IMAGE SORCE: JUPITERIMAGES

Leave a Reply