Maintaining sinus patency after functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) has long been an issue; as many as 23 to 47 percent of patients require revision surgery after FESS (Laryngoscope. 1993;103(10):1117-1120; Laryngoscope. 2004;114(5):811-813.) Now, a new drug-eluting, bioabsorbable stent manufactured by Intersect (Palo Alto, Calif.) is being billed as a “breakthrough treatment [that] improves outcomes for sinus surgery,” according to a news release from the company. The device, which received pre-market approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in August, has been studied since 2008. It is currently available in Texas, New York, Philadelphia, New Jersey, Atlanta, Ohio and Kentucky.

Explore This Issue

December 2011But is the drug-eluting stent, called Propel, truly a game-changer, or is it simply another step in the treatment of CRS?

History of Sinus Stenting

“The concept of stenting a sinus at the end of a procedure goes back decades, and countless devices have been proposed and used over the years,” said Martin Citardi, MD, FACS, chair of the department of otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston. “None of them proved themselves to work very well over a period of time.”

Prior to the 1950s, some otolaryngologists placed stents made of latex rubber in the sinus outflow tracts after sinus surgery, said Stephen Freeman, MD, FACS, an otolaryngologist currently in private practice in Carmel, Ind. The problem was that latex often caused tissue reactions, creating scar tissue. By the 1950s and 60s, sinus stents had developed a bad reputation.

Dr. Freeman and others, though, remained intrigued by the possibility of sinus stenting. “In the late 1980s, I would take urinary catheters made out of silicone, trim them [down to] a small tube and place them in the sinuses,” Dr. Freeman said. After one patient’s stent popped out unexpectedly, Dr. Freeman created the bi-flanged sinus stent now known as the Freeman stent.

The device, designed for use in the frontal sinuses, appeared to help maintain sinus patency post-surgery, although stent blockage and build-up of granulation tissue around the stent were noted in clinical studies (Laryngoscope. 2000;110(7);1179-1182). Premature degradation of the plastic tip of the insertion device led to the removal of the Freeman stent from the market for a two-year period; it’s currently back on the market.

Meanwhile, otolaryngologists’ understanding of rhinosinusitis has continued to evolve. “Chronic sinusitis is not a simple plumbing problem,” said David Kennedy, MD, professor of rhinology at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in Philadelphia. “Just opening up the sinus is rarely a solution to resolving the disease, because there’s often a diffuse inflammatory problem as well.”

In 2009, Acclarent (Menlo Park, Calif.) introduced the Relieva Stratus as a way to address sinus mucosal inflammation. An article in Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology described the Stratus as a “drug-eluting sinus stent … for [the] minimally invasive treatment of chronic ethmoid mucosal disease” (2009;20(2):108-113). But in a departmental newsletter published in 2008, Dr. Citardi said the device is more like a “leaky balloon” than a traditional stent (UT ORL Update. 2008). That’s because the stent is filled with triamcinolone acetate, a local anti-inflammatory agent, and emits the drug over a two- to four-week period, at which time the device is removed in the office setting (Op Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;20(2):108-113). At least one case of orbital violation following placement of the drug-eluting ethmoid stent has been reported in the literature (Int Forum Allergy Rhinol [published online ahead of print August 26, 2011]).

Enter Propel

Despite many different interventions and surgical techniques, recurrent polyposis, inflammation, adhesion formation, middle turbinate lateralization and stenosis of surgically enlarged sinus ostia remain common problems following sinus surgery. Typical post-operative measures, such as the lysis of surgical adhesions or local or systemic anti-inflammatory treatment, are time consuming and present the potential for complications. Systemic anti-inflammatory treatment, though potentially effective, exposes patients to unnecessary system-wide effects.

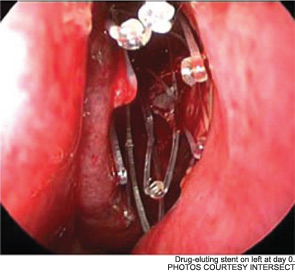

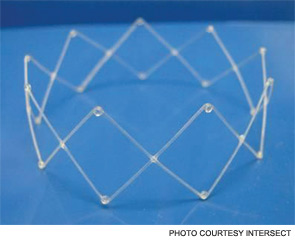

Bradley Marple, MD, professor and vice chairman of the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, discussed these challenges, as well as the potential of the Propel stent, in September at the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) annual meeting in San Francisco. Unlike previous sinus stents, he said at the meeting, Propel mechanically props the sinus ostia open while delivering mometasone furoate directly to the sinus mucosa over a 30-day period.

“A lot of the focus has been on the issue of sustained drug delivery, but the device, by virtue of expanding, holds the structures within the nose in an appropriate position to help prevent scarring and movement of structures that could cause problems, such as lateralization of the middle turbinate,” Dr. Marple said in a post-meeting phone interview.

To date, three clinical research trials have examined Propel: a randomized, double-blind pilot study (Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(1):23-32), the ADVANCE safety study and ADVANCE II, a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Dr. Marple presented the ADVANCE II at the AAO-HNS annual meeting. Joseph K. Han, MD, an associate professor of rhinology and director of the divisions of allergy and rhinology and sinus-skull base surgery at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, presented a meta-analysis of the data at the same meeting. Publication is pending on the meta-analysis data.

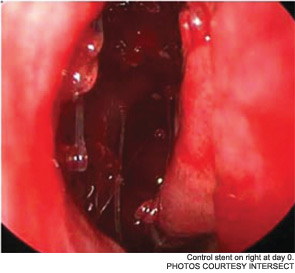

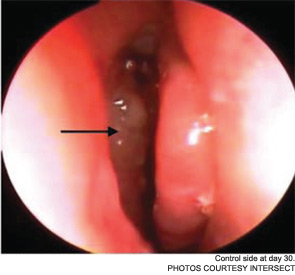

The pilot study enrolled 43 patients; 38 were randomized to receive a drug-eluting stent on one side and a non-drug-eluting stent on the other. The remaining five patients received bilateral sinus stents. No device-related adverse effects were noted during the six-week trial period, and post-operative inflammation, polyposis and adhesion were significantly less common in sinuses with drug-eluting stents than in the sinuses with non-drug-eluting stents The adhesion rate in sinuses without drug-eluting stents was 21.1 percent, compared with 5.3 percent in the sinuses with a drug-eluting stent. The pilot study also demonstrated the safety of the bioabsorbable stent. By day 30, an average of less than 10 percent of the stent material remained; by the end of the study, the stent material was completely absorbed (Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(1):23-32).

As Dr. Marple explained during his AAO-HNS presentation, the ADVANCE trial studied the device in 50 patients; ADVANCE II enrolled 105 patients with CRS refractory to medical management. All patients underwent FESS prior to deployment of the stent. As in the pilot study, patients were randomized to receive a non-drug-eluting stent on one side and the drug-eluting stent on the other. An independent panel of three sinus surgeons reviewed and graded endoscopic views of the treated sinuses at post-op day 30. Compared with the control sinuses, the drug-eluting stent provided a 29 percent (p=0.0280) relative reduction in post-operative interventions, a 52 percent (p=0.0053) decrease in lysis of adhesions and a 29 percent decrease (p=0.0023) in oral steroid prescriptions. No clinically significant ocular effects were noted; two device-related adverse events were coded as sinusitis and relieved without difficulty.

While the pilot and ADVANCE II research studies did not specifically examine patients’ quality-of-life pre- and post-stenting, the ADVANCE study assessed patients’ symptoms for six months using Sino-Nasal Outcome Test and RSDI quality of life instruments. Significant improvements in patient outcomes were reported during the six-month period, Dr. Han, who participated in the research and conducted the meta-analysis, said in an interview after the AAO-HNS meeting. A number of his patients also reported less pain on one side than the other, though neither the patient nor the clinician knew with certainty which side contained the drug-eluting stent and which contained a plain version of the stent.

Patient Population

Patients in the clinical research studies had a “relatively significant” disease burden, Dr. Marple said in an interview after the AAO-HNS meeting. All had a minimum Lund-MacKay stage of six; the average was 12.4. Patients with insulin-dependent diabetes, acute or invasive fungal sinusitis, an oral-steroid dependent condition and a history of immunodeficiency, glaucoma or ocular hypertension were excluded from the studies.

The device has not yet been studied in pediatric patients, but according to Dr. Han, the drug-eluting stent would be safe for use in the pediatric population. “Mometasone has a typical bioabsorbtion rate that is very low, less than one percent,” he said.

According to Dr. Citardi, additional research is needed to determine which patients are most likely to benefit from implantation of drug-eluting stents after FESS. “The incremental benefit of the device in the study patient population, which was most likely a primary level of sinus surgery population, is probably different than in patients who have had multiple procedures,” he said. “You also have to weigh the benefit against the actual cost of the device.”

Initial Response

Some otolaryngologists are looking forward to applying the technology to clinical practice. “I think the most common question after our presentation at the [AAO-HNS Annual Meeting] was, ‘Where do we get it?’” Dr. Han said. “The next most common question was, ‘Can you put this in at the office?’”

To date, in-office use has not been studied. Dr. Han said in-office deployment of the drug-eluting stent is theoretically possible.

Dr. Freeman said that there are still many questions that need to be answered before he recommends stents to patients: “Do patients still have to be periodically on antibiotics? Do they have to periodically use nasal or oral steroids? Do they still have recurring infections or need to have additional endoscopic surgery down the road?”

Dr. Citardi said additional research may help to refine the steroid dose as well. “One of the concerns is that the total dose of mometasone in the device is actually pretty low.

I suspect that many patients with more severe forms of inflammation of the sinuses will need a higher steroid dose,” he said. “We also need to be careful of the impact of the dissolving material on the sinus mucosa. That’s something that may be hard to fully describe in a small study.”

Despite the need for additional research, Dr. Marple sees potential for drug-eluting stents. “I think this is just scratching the surface of an exciting new era in manipulations and treatment of the paranasal sinuses,” he said. “This mixes the mechanical aspects of therapeutic intervention of the paranasal sinuses, which surgery has provided in the past, with medications that allow suppression of the inflammatory component. It’s this overlap in device and medication that really positions us to better treat many patients with chronic sinus disease.”

The real test, Dr. Citardi said, will be “the test of time.” “Over the next couple years, as people start to use the stent, we’ll be able to better define its role and use,” he said.

Disclosures: Dr. Freeman has reported a financial relationship with InHealth Technologies, the company that manufactures and distributes his Freeman nasal stent. Dr. Kennedy is on the medical advisory board of Intersect ENT. None of the other sources reported any relevant financial ties.

Leave a Reply