Does smoking prevent sinus surgery from making patients feel better? Over the years, evidence and expert opinion have varied on this topic. As a result, some surgeons refuse to provide endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) for active smokers, while others will operate because they believe surgery improves quality of life.

“First, you have to understand the way we look at improvement after ESS,” said Douglas Reh, MD, associate program director of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. One measure is objective outcomes, the things you can see on CT scans or in endoscopy scores. The second is health-related quality of life (QOL) measurements, which, in Dr. Reh’s opinion, are more important.

The Conflicting Evidence

“I think that, traditionally, most people thought that smokers would have worse outcomes after sinus surgery, because smoking is bad for you,” said Rodney Schlosser, MD, a professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. But, “as they did the research and looked at quality of life, among other things, they found that smokers did not have worse outcomes.”

For example, a November 2009 study of 235 patients published in Laryngoscope (119(11):2284-2287) reported that over a four-year period both smokers and nonsmokers continued to maintain a highly significant improvement in SNOT-20 scores following ESS. The authors noted that “although smoking remains a well-documented cause of medical morbidity, smokers maintained an improvement in quality of life after long-term follow-up.” They said their findings are consistent with other prospective studies (Laryngoscope. 2005;115(12):2199-2205).

The study’s senior author, Stilianos E. Kountakis, MD, PhD, chief of rhinology at Georgia Health Sciences Health System in Augusta, Ga., told ENT Today that his team plans a follow-up evaluation that will look at QOL and SNOT-20 scores for these patients eight years after surgery.

A prospective study of 784 patients published in International Forum of Allergy and Rhinology (2011;1(3):145-152) found that smokers and nonsmokers experienced similar improvement in health-related quality of life. The authors noted, however, that while overall changes in endoscopy scores did not differ between smokers and nonsmokers, there was a significant difference in the prevalence of worsening post-operative endoscopy scores between heavy smokers (≥20 cigarettes per day), light smokers (<20 cigarettes per day) and nonsmokers (100 percent, 33 percent, and 20 percent, respectively; p = 0.002).

Nonetheless, “we do surgery to improve a patient’s quality of life, not the appearance of their sinuses,” said Timothy Smith, MD, director of the Oregon Sinus Center, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland.

But David Kennedy, MD, professor of rhinology at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center and Veterans Administration Hospital in Philadelphia, puts a higher weight on the endoscopy readings. His goal is resolution of the disease and getting the mucosa to settle down and become stable; on the research side, his team studies the underlying persistent inflammation.

“We look primarily at the endoscopic outcomes, not just quality of life.”

“We look primarily at the endoscopic outcomes, not just quality of life.”—David Kennedy, MD

Dr. Kennedy said there are two things that are important in identifying outcome after ESS: the extent of disease and patients who continue to smoke. In a study (Laryngoscope. 1998;108(2):151-157) in which researchers enrolled 120 patients and followed them for eight years, Dr. Kennedy and his colleagues found that more smokers than nonsmokers needed revision surgery. Based on these findings and his personal experience, Dr. Kennedy said he refuses to do elective sinus surgery unless the patient has quit smoking for approximately six weeks prior to surgery. He will operate on smokers if there are complications of the sinusitis or a neoplasm.

“We look primarily at the endoscopic outcomes, not just quality of life,” Dr. Kennedy said, noting that persistent asymptomatic disease is common after ESS in smokers. “All patients feel better after ESS, so it probably doesn’t matter if all you’re looking for is symptom improvement in the short to medium-term follow-up period.”

Meanwhile, several studies have found that smokers do worse after ESS. For example, a study published in 2004 found that smoking was associated with statistically worse outcomes after ESS based on average SNOT-16 scores (Laryngoscope. 114(1):126-128). The smokers’ SNOT-16 scores averaged 27.5, versus 18.2 for the non-smokers. Passive smoke exposure in smokers increased the average SNOT-16 score to 30.6. The average SNOT-16 score in the ex-smoking nonsmokers was 22.1, and passive exposure in this group increased the average SNOT-16 score to 25.5.

A 2011 article in Rhinology (49(5):577-582) showed that smokers had worse post-operative outcomes than their nonsmoking counterparts, including nasal blockage, loss of smell, frontal headache, postnasal drip, muco-purulent rhinorrhea and watery rhinorrhea, over an observation period of two to nine years.

“The significance of [the 2011 Rhinology paper] is to underline that smoking may negatively influence the post-operative course in chronic rhinosinusitis in terms of higher risk of unresponsiveness to further treatment, leading to revision surgery,” said the study’s first author Antoni Krzeski, MD, PhD, a professor within the department of otolaryngology at Warsaw Medical University, Poland. “It is particularly important when discussing informed consent with the patient.”

Dr. Krzeski said the conflicting study results on the effect of smoking on ESS outcomes could relate to the variety in study designs. “More uniform groups (inclusion/exclusion criteria), which are more difficult to obtain, would probably solve the problem,” he said, The uniform groups, he said, would consist of patients who do not have underlying disease as well as patients with a disease entity, such as aspirin hypersensitivity, that would predispose them to recurrence. “When speaking of the necessity of reoperation these problems need to be estimated,” he added.

Educational Efforts with Smokers

While everyone agrees that smokers should be counseled to stop for numerous health reasons, Dr. Reh and his colleagues have unpublished data suggesting that both primary care doctors and otolaryngologists are “very bad about discussing smoking with patients and counseling them to stop.”

Otolaryngologists interviewed for this article, however, all said they counsel patients to stop smoking and, most often, refer smokers back to their primary care physicians to find the program that best suits them. All were unaware of any studies that had found a “best” smoking cessation program for their patients.

“I don’t believe there is a cookbook recipe for smoking cessation,” said Oregon’s Dr. Smith. “Often it involves different interventions for different patients, depending upon their psychosocial situation. For some people, this means pharmaceutical intervention, for others, a social support group or efforts to address issues in their lives that prevent them from quitting. I think the best you can do is to help a patient become familiar with smoking cessation programs that are available in your community.”

“Sometimes people can’t be convinced to stop,” said Dr. Kountakis. “Smoking is one of the most difficult habits to break. It’s a severe addiction.”

Dr. Kountakis said his dilemma is how to help patients who refuse to quit. “When sinus surgery is necessary, I operate to improve their quality of life,” he said. “I, in no way, support their continued smoking and insist that they participate in smoking cessation programs.”

Dr. Schlosser said a patient’s tobacco addiction shouldn’t affect the surgeon’s decision to operate. “If a smoker is going to get better, even if they continue to smoke, why not offer them a treatment that will improve their quality of life?” he said.

Dr. Smith said most patients with sinusitis have quit smoking by the time they are considering surgery. For example, in one of his studies with 784 chronic rhinosinusitis patients, only 8 percent were smokers (Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2011;1(3):145-152).

A Novel Educational Tool

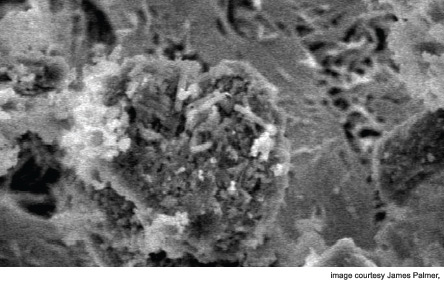

James N. Palmer, MD, director of rhinology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, uses visual argument to help convince his smoking patients to stop. He shows them pictures of nasty bacterial biofilms that are associated with scar formation and encouragement of re-infection.

“Otolaryngologists can tell patients that smoking is associated with the need for more surgery, but providing them with a descriptive example of these coral reef-type structures in their sinuses may help persuade them to stop,” he said.

In a study published last year (PLoS One 2011;6(1):e15700), Dr. Palmer and his team demonstrated that tobacco smoke exposure induces biofilm formation in respiratory bacteria and that smoking cessation should revert bacteria back to a smoke-naïve phenotype.

Telling patients about biofilms and how they decrease outcome after surgery “is something patients like,” he said. “It tells them they will do worse because smoking increases biofilm formation in their sinuses.”

Leave a Reply