The question of how soon to give antibiotics to children with acute otitis media (AOM) is receiving renewed attention with the publication of two studies that show the benefit of immediate treatment over the “wait-and-see” approach recommended in the 2004 guidelines of the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAP/AAFP) (Pediatrics. 2004;113:1451-1465).

Explore This Issue

April 2011The new studies, one from Pittsburgh (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:105-15) and the other from Finland (N Engl J Med. 2011;364:16-26), both show a significant reduction in symptoms and clinical failure rates in children with AOM who were younger than two years of age and were treated with antibiotics compared to those who were not treated.

For most physicians in the U.S. who continued immediate treatment of AOM with antibiotics even after the 2004 recommendations, the new studies add weight to that decision. Physicians who have adopted a “wait-and-see” approach, largely in response to growing concern over the antibiotic overuse and multi-drug resistant bacteria that helped drive the 2004 recommendations, may need to rethink which children to observe before initiating treatment if necessary.

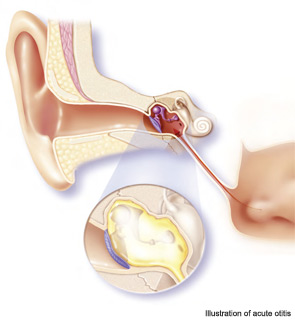

However, a key message of both studies is that optimal treatment of AOM depends on accurate diagnosis. For all physicians who treat AOM, therefore, the debate over whether to treat with antibiotics immediately or observe really hinges on identifying which children truly have AOM.

“The question is not so much about the use of antibiotics; it is the big clinical dilemma of accurate diagnosis of AOM,” said Julie L. Wei, MD, associate professor and pediatric otolaryngologist at the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Kansas City. “The overprescription of antibiotics comes from the misdiagnosis or overdiagnosis of AOM.”

Spotlight on Accurate Diagnosis of AOM

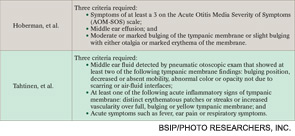

Recognizing the importance of accurate diagnosis of AOM for optimal treatment, investigators of both studies used stringent diagnostic criteria (see Table 1).

“These are the best articles written on AOM because they used strict diagnostic criteria,” “The strict diagnosis means that only children with true acute otitis media were included and children with otitis media with effusion (OME) were excluded,” said Allan S. Lieberthal, MD, a pediatrician at Kaiser Permanente, Panorama City, Calif., and one of the authors of the 2004 AAP/AAFP guidelines.

According to Dr. Lieberthal, prior studies, including those that informed the recommendation for the “wait-and-see” approach of the 2004 AAP/AAFP guidelines, included children with OME, and the results of those studies showed poorer outcomes for children who were observed compared to those treated.

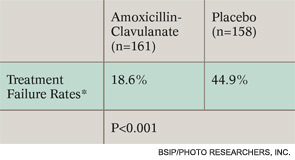

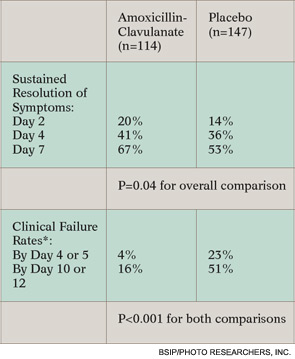

Contrary to these findings, the new studies show that immediate treatment was associated with a significant benefit, both in resolution of symptoms and in rate of clinical failure in children with clearly defined AOM (see Table 2 on this page and Table 3 on p. 20).

“These studies show a benefit of immediate antibiotic treatment in children under age two years with a quite certain diagnosis of AOM,” said Alejandro Hoberman, MD, chief of general academic pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, and lead author of the Pittsburgh study. Prior to these studies, he said, the appropriate treatment strategy for young children with stringently defined AOM had remained unclear.

For Aino Ruohola, MD, PhD, of the department of pediatrics at Turku University Hospital in Turku, Finland, and the senior author of the Finnish study, the results mean that children with a certain diagnosis of AOM benefit from antibiotics. “However, those with otoscopic signs not definitely indicating acute otitis media should not receive antibiotics,” she said.

To Treat or Not: Still Some Gray

Although these studies clearly demonstrated that children with strictly defined AOM benefit from immediate antibiotics, they also showed that even some of these children get better without antibiotics. Another way to read the 45 percent treatment failure rate in the Finnish study for the children not receiving antibiotics, for example, is that 55 percent did not have treatment failure.

“The Finnish study emphasized that about one-half of the placebo group got better,” said Dr. Wei. “Both studies agree that the problem is you just don’t know who will end up being the half that get better without antibiotics.”

One area that may play into this issue is the appropriate use of analgesic agents. The 2004 AAP/AAFP guidelines strongly recommend the use of oral and topical analgesics for pain management in children with AOM.

Although both studies reported comparable use of these agents in both the treatment and placebo groups, not all patients were treated with these agents. Rather, both studies instructed parents to give pain medication on an as needed basis and to keep track of their use. The Finnish study reported an overall use in 84.2 percent of the children treated with antibiotics and 85.9 percent in the placebo group. The Pittsburgh study reported that the mean daily number of doses of acetaminophen administered was 0.37 and 0.43 in the treatment and placebo groups, respectively.

According to David M. Spiro, MD, MPH, associate professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, the lack of consistent use of pain medications, particularly in the Pittsburgh study, more than likely influenced the results. “It is likely there would be no statistically significant differences between the two groups if all patients in both groups had been given both oral analgesics and ear drops,” he said.

—Julie L. Wei, MD

Dr. Wei thinks the fact that all children in the study were not prescribed the routine use of pain medications may have introduced a flaw into the study. “When you’re looking at one intervention, you must control for all other factors,” she said, adding that treatment of pain in AOM can be highly effective and can influence whether or not antibiotics are prescribed.

Dr. Hoberman emphasized that no difference was found in the use of analgesics between the two groups and that the aim of the study was not to evaluate pain medication.

Dr. Lieberthal expressed doubts about the effect the use of analgesics would have on the primary outcomes of the studies.

*Determined by composite of six components: no improvement in overall condition by day three, worsening of child’s overall condition, no improvement in otoscopic signs by day eight, perforation of the tympanic membrane, severe infection, any reason for stopping study drug.

Although it is uncertain whether the lack of consistent pain medication use introduced a variable that may have influenced the results of these studies, all experts consulted agree that better diagnosis of AOM may be the key to limiting antibiotic use.

Even with strict diagnostic criteria, however, whether or not to treat immediately may be a judgment call.

“I feel that the physician and parent, using shared decision making, may choose to observe initially and start antibiotics if symptoms persist,” Dr. Lieberthal said, reiterating that the majority of patients in the placebo groups of both studies improved despite meeting stringent diagnostic criteria.

Leave a Reply