Presentation: A 14-year-old boy sustained blunt trauma to the forehead from a foul-tipped baseball. Significant past medical history consisted of allergic rhinitis treated with over-the-counter cetirizine (Zyrtec). On examination, the patient had right frontal sinus depression with overlying edema. There were no palpable nasal bone or orbital rim abnormalities. Baseball threads were seen on the overlying skin as well as ecchymosis on the nasal dorsum and under both eyes (Figure 1).

The patient had numbness of the right forehead from the eyebrow to the hairline. Visual acuity and ocular movement were normal. Nasal speculum and endoscopic examinations revealed no intranasal abnormalities. There was no evidence of clear rhinorrhea to suggest cerebral spinal fluid leak.

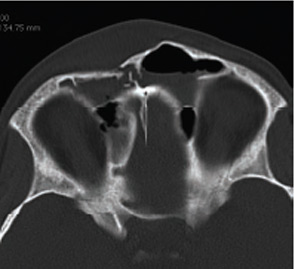

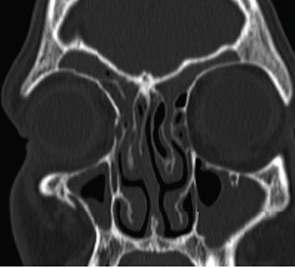

A CT scan (Figures 2 and 3) was obtained.

How would you manage this patient? Go to the next page for discussion of this case.

Figure 7: Postoperative frontal view showing well-healed, disguised eyebrow scar and smooth bony surface without any visible plates or screws.

Figure 7: Postoperative frontal view showing well-healed, disguised eyebrow scar and smooth bony surface without any visible plates or screws.Management: Axial CT scan of the sinuses showed a depressed, comminuted anterior table frontal sinus fracture as well as a non-displaced right nasal bone fracture (Figure 2, p. 4). The injury did not cause obstruction of the nasofrontal duct, and the fracture was completely extradural.

Coronal images showed mucosal thickening in the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses, as well as patent nasofrontal recess (Figure 3, p. 4). Noted of significance is the hyperaerated frontal sinus, which is most susceptible to this type of injury.

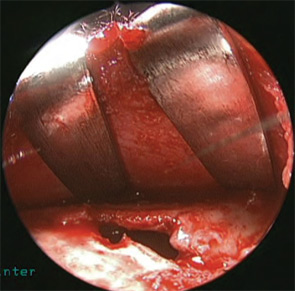

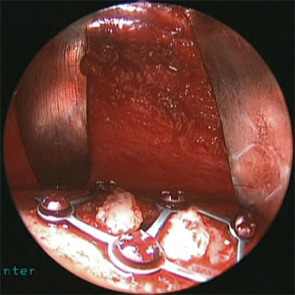

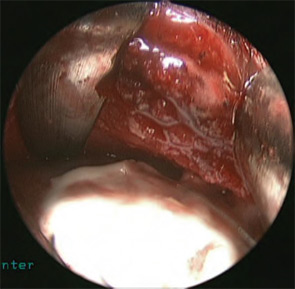

Because the fracture caused a significant cosmetic skull deformity, the patient was taken to the operating room for open reduction and internal fixation. Neither a cranioplasty nor cerebral spinal fluid repair was necessary. Exposure to the fracture was accomplished via a 3cm eyebrow incision made directly into the eyebrow, beveling the scalpel toward the direction of the hairs. The periosteum was incised with a scalpel and elevated over the area of the depressed fracture. Segments of loose, comminuted bone were removed and saved, noting the position of each piece. Using hooks and elevators, the depressed fracture was elevated into its proper position (Figure 4, p. 4). A zero-degree endoscope was used to visualize the frontal sinus through the fracture to insure complete removal of bone fragments and patency of the frontal recess. A two-squared mini-plate with five screws was used to secure the major bone fragment in correct position. The smaller bone fragments were replaced, however, because severe comminution areas remained with missing bone fragments (Figure 5). Hydroxyapatite cement was used in these areas to avoid depression, strengthen the repair and enhance cosmetic appearance. The cement was also used to cover the plate and screw heads to develop a smooth surface (Figure 6). The wound was closed in layers with absorbable sutures.

Postoperatively, the patient did well. He reported no sinus infections or headache. Forehead numbness improved, but some hypesthesia remained. The patient’s forehead was symmetrical, and there was no visualized or palpable evidence of the plate or screws. The eyebrow incision was healing well with minimal scarring (Figure 7). On lateral view, there was no depression.

Discussion: Frontal sinus fractures usually occur as the result of high velocity impact that occurs in such situations as motor vehicle collisions, assaults, industrial accidents and sports injuries. Although motor vehicle accidents continue to be the most common cause of frontal sinus fractures, incidence has fallen significantly with the aggressive enforcement of seat belt laws.1 This patient represents an interesting case of local blunt trauma caused by a foul-tipped baseball hitting directly over the most aerated portion of the frontal sinus. Recreational accidents are reported to cause 9 percent of cases.1 In a review of sports-related injuries occurring in Europe, where baseball is uncommon, 40 percent were caused by soccer and rugby, 34 percent were related to extreme sports, and 6 percent were related to martial arts.2

This case highlights two operative techniques. The endoscope was used through a small brow incision to enable better visualization of the fracture and sinus outflow tract from above. A coronal approach was avoided, preventing potential complications and accelerating recovery.3 The case also presents an operative technique involving the use of hydroxyapatite cement. Hydroxyapatite cement has been shown to enhance the osseointegration of implants and small fragments. It appears to provide a significant advantage over acrylic (methyl methacrylate) as a cranial replacement when in contact with the paranasal sinuses in terms of surgical site infection.4 Hydroxyapatite is also extremely easy to use and allows contouring to complex three-dimensional structures. In this case, we used the cement to stabilize small bone fragments, to fill in any defects where missing comminuted bone fragments could not be realigned and to create a smooth surface of the anterior skull base. Between plating and hydroxyapatite cement, the strength and stability of the repair was markedly enhanced. As a result of this type of repair, this patient, who enjoyed both excellent cosmetic and functional results, was able to return to playoff games within two weeks of surgery.

References:

- Strong EB, Pahlavan N, Saito D. Frontal sinus fractures: a 28-year retrospective review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135(5):774-779.

- Maladière E, Bado F, Meningaud JP, et al. Aetiology and incidence of facial fractures sustained during sports: a prospective study of 140 patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001:30(4);291-295.

- Steiger JD, Chiu AG, Francis DO, et al. Endoscopic-assisted reduction of anterior table frontal sinus fractures. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(10):1936-1939.

- Friedman CD, Costantino PD, Snyderman CH, et al. Reconstruction of the frontal sinus and frontofacial skeleton with hydroxyapatite cement. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2000;2(2):124-129.

—Submitted by Brent J. Benscoter, MD, and James A. Stankiewicz, MD, department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery, Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, Ill.

Leave a Reply