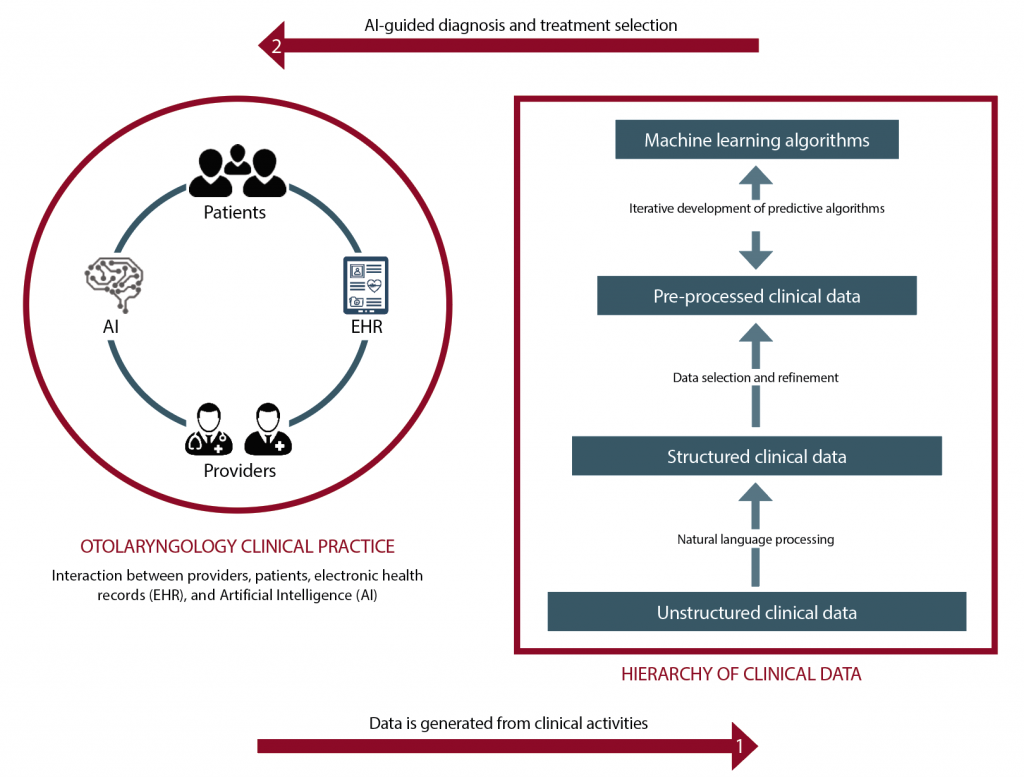

(click for larger image) The figure shows how AI can be implemented to support otolaryngology practices. A large amount of data is generated from clinical interactions (e.g., office visits, imaging studies, surgeries, pathology), which can then be used to build machine learning algorithms, which can in turn be used to provide clinical decision support.

Explore This Issue

February 2019© Graphic by Selina Zapata Bur

Applying AI and ML

AI relies on using large amounts of patient data to make accurate predictions, but because ML algorithms have no inherent knowledge about otolaryngology, they need data to “learn” to make predictions, Dr. Bur said. The amount of data required depends on several factors, including the problem’s complexity and the type of learning algorithm. The more data that is available, the better the ML will perform.

By analyzing how similar patients have responded to past treatments, machine learning can provide information based on many more patient experiences than any individual physician could incorporate into their medical decision making —Andrés Bur, MD

Elizabeth A. Blair, MD, professor of surgery in the section of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Chicago, pointed out that using AI and ML requires the input and acumen of expert clinicians to determine where gaps exist and what information would help physicians. This could assist physicians in selecting the type of treatment for patients, finding alternative therapies that could be effective, or predicting and determining if they are at increased risk for complications for a certain treatment.

Dr. Moberly said some in radiology and pathology have considered the physician’s future role to be an “information specialist” responsible for managing the information extracted by AI in the clinical context of the patient (JAMA. 2016;316(22):2353-2354). In a field such as otolaryngology, however, the physician will need to remain much more than an information specialist; AI should be an aid to the physician, not a substitute (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:191).

Dr. Friedland agreed. “AI and ML will serve as another way to provide clinical information, but won’t replace physicians,” he said. “Physicians already integrate the results of radiographs, audiograms, and blood tests into the clinical picture to help formulate a diagnosis. AI will similarly provide more information to aid in such decision making.”

Possible Drawbacks

Despite its potential, AI raises new ethical concerns that remain unanswered. First, AI development and clinical implementation requires large amounts of patient data. How should the privacy of patient information be weighed against the need to leverage this data for medical innovation? Secondly, bias in the data used to train ML algorithms produces bias in the decisions of the algorithms themselves. How can we ensure that AI is generalizable and safe for all patients? And lastly, if medical decision making shifts from physicians to intelligent machines, how will the relationship between otolaryngologists and their patients change? Along these same lines, who is responsible when an AI system causes patient harm?

Another concern is that technology expansion of the kind that will occur through the use of AI and ML approaches can drive a wedge between patients and physicians (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:191). “They can’t serve as a replacement for careful history-taking and a physical exam,” Dr. Moberly said. “Astute clinicians are adept at considering the whole patient’s picture, which could be missed by relying solely on objective data points plugged into an AI algorithm. As in other medicine fields, it is essential to properly evaluate AI as well as appropriately train users.”