The use of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) in the field of otolaryngology is in its infancy; most current initiatives are in the research stage. But the benefits of employing these technologies show great promise.

Explore This Issue

February 2019AI requires large datasets of patient characteristics, disorders, and outcomes. The technology can be used in almost any subspecialty in otolaryngology. “The most direct application is to develop clinical decision support systems from data,” said David R. Friedland, MD, PhD, professor and vice chair of otolaryngology and communication sciences at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. This could be as simple as recommending specific tests, given a specific complaint and symptomatology. AI would mine prior data and identify which test provides the most clinically and cost-effective benefit, and would use real patient data, in real time, to constantly upgrade its evidence-based recommendations.

Andrés Bur, MD, assistant professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Kansas in Kansas City, believes that AI’s biggest impact may be to increase personalized care in otolaryngology. Companies such as Amazon and Google use ML technologies to understand their customers based on data. “We can use AI to increase personalization in otolaryngology and in health care in general by doing the same thing,” he said. ML can be used to predict clinically important outcomes and determine the best treatment for an individual patient based on data. These types of predictive algorithms could, in the future, be used to build clinical decision support to make personalized treatment recommendations supported by data.

“By analyzing how similar patients have responded to past treatments, ML can provide information based on many more patient experiences than any individual physician could incorporate into their medical decision making,” Dr. Bur said.

AI could also revolutionize how otolaryngologists interact with electronic health records (EHR). According to recent estimates, for every hour that physicians provide face-to-face clinical care to patients in the outpatient setting, they spend nearly two additional hours on EHR documentation and desk work (Ann Intern Med. 2016; 165:753-760). “By recording and automatically extracting content from clinical encounters using natural language processing, virtual scribes have the potential to reduce the burden of clinical documentation,” Dr. Bur said.

Current Initiatives

In a review article that has been accepted for publication in Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, Dr. Bur and his team of investigators identified 54 articles in the otolaryngology literature focused on AI. “Interestingly, more than half were published in the past two years, highlighting the recent explosion of interest in AI research,” he said. “There is great interest in AI and ML in our field; articles published in every specialty in our field center around using AI technologies.”

Aaron C. Moberly, MD, an assistant professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, and colleagues have used AI to develop software called “Auto-Scope” to help clinicians perform more accurate diagnoses for the ear using digital otoscopy. “This initially involved classifying images as normal or abnormal, but will eventually expand to build enhanced composite images and provide more specific information on particular types of pathology,” he said.

Dr. Friedland and his team are studying ML and AI components in vestibular disorders. Specifically, they are looking at methods to aid otolaryngologists and primary care providers in formulating better differential diagnoses when a patient has dizziness. They use a direct-to-patient survey to learn about their symptoms. “By correlating large numbers of patient responses with an expert-provided diagnosis, we hope to identify patterns, which may improve diagnostic accuracy,” he said.

Another area Dr. Friedland has studied is using natural language processing, a form of AI that interprets natural speech or written documentation, to identify expert descriptors of specific vestibular conditions. “This may help non-experts develop language usage that better obtains a patient history and allows for more accurate formulation of a differential diagnosis,” he said.

Naweed Chowdhury, MD, assistant professor of otolaryngology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, and colleagues have investigated applications of AI and ML in rhinology and skull base surgery. They showed that a convolutional neural network called “Inception” could be retrained to classify the patency of the osteomeatal complex on a computerized tomography scan with about 85% accuracy (Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019;9:46-52). More recently, they used a ML model known as a random forest to demonstrate that the mucus cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 were predictive of baseline olfactory function in chronic sinusitis patients.

In rural areas, digital slides read elsewhere could be used to assist in decision making and counseling patients.

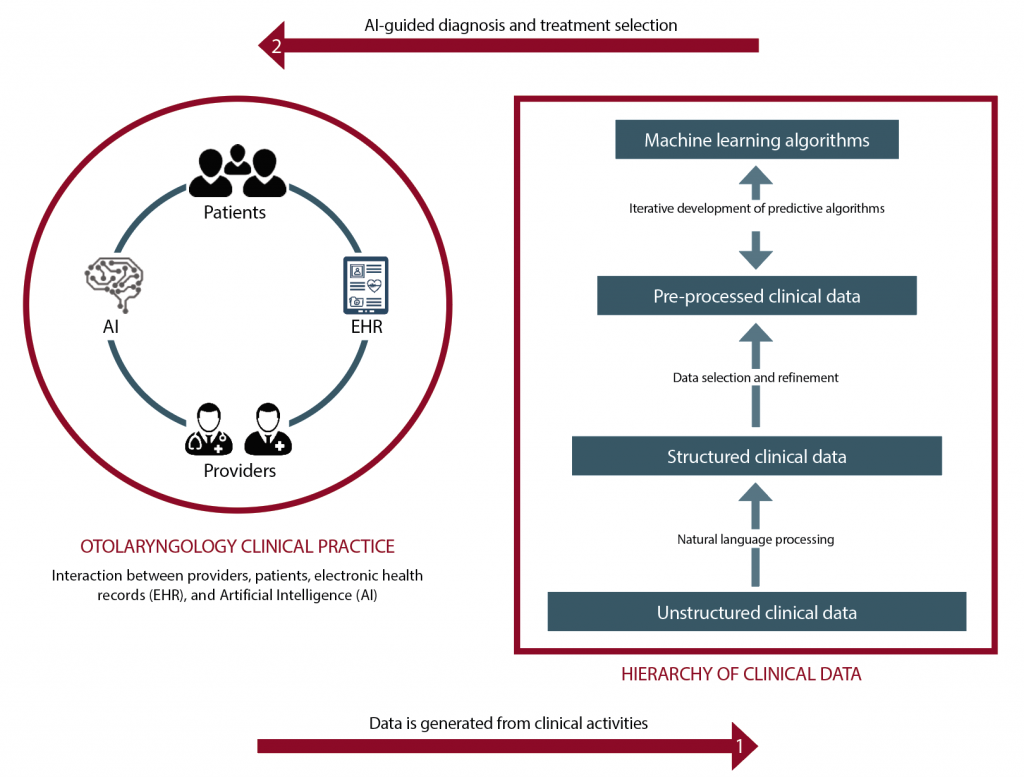

(click for larger image) The figure shows how AI can be implemented to support otolaryngology practices. A large amount of data is generated from clinical interactions (e.g., office visits, imaging studies, surgeries, pathology), which can then be used to build machine learning algorithms, which can in turn be used to provide clinical decision support.

© Graphic by Selina Zapata Bur

Applying AI and ML

AI relies on using large amounts of patient data to make accurate predictions, but because ML algorithms have no inherent knowledge about otolaryngology, they need data to “learn” to make predictions, Dr. Bur said. The amount of data required depends on several factors, including the problem’s complexity and the type of learning algorithm. The more data that is available, the better the ML will perform.

By analyzing how similar patients have responded to past treatments, machine learning can provide information based on many more patient experiences than any individual physician could incorporate into their medical decision making —Andrés Bur, MD

Elizabeth A. Blair, MD, professor of surgery in the section of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Chicago, pointed out that using AI and ML requires the input and acumen of expert clinicians to determine where gaps exist and what information would help physicians. This could assist physicians in selecting the type of treatment for patients, finding alternative therapies that could be effective, or predicting and determining if they are at increased risk for complications for a certain treatment.

Dr. Moberly said some in radiology and pathology have considered the physician’s future role to be an “information specialist” responsible for managing the information extracted by AI in the clinical context of the patient (JAMA. 2016;316(22):2353-2354). In a field such as otolaryngology, however, the physician will need to remain much more than an information specialist; AI should be an aid to the physician, not a substitute (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:191).

Dr. Friedland agreed. “AI and ML will serve as another way to provide clinical information, but won’t replace physicians,” he said. “Physicians already integrate the results of radiographs, audiograms, and blood tests into the clinical picture to help formulate a diagnosis. AI will similarly provide more information to aid in such decision making.”

Possible Drawbacks

Despite its potential, AI raises new ethical concerns that remain unanswered. First, AI development and clinical implementation requires large amounts of patient data. How should the privacy of patient information be weighed against the need to leverage this data for medical innovation? Secondly, bias in the data used to train ML algorithms produces bias in the decisions of the algorithms themselves. How can we ensure that AI is generalizable and safe for all patients? And lastly, if medical decision making shifts from physicians to intelligent machines, how will the relationship between otolaryngologists and their patients change? Along these same lines, who is responsible when an AI system causes patient harm?

Another concern is that technology expansion of the kind that will occur through the use of AI and ML approaches can drive a wedge between patients and physicians (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:191). “They can’t serve as a replacement for careful history-taking and a physical exam,” Dr. Moberly said. “Astute clinicians are adept at considering the whole patient’s picture, which could be missed by relying solely on objective data points plugged into an AI algorithm. As in other medicine fields, it is essential to properly evaluate AI as well as appropriately train users.”

Challenges

A major impediment to using AI in otolaryngology stems from the fact that current electronic health records (EHRs) are designed primarily for documentation and billing purposes, Dr. Bur said. Although they contain an enormous amount of patient data, most data is unstructured and not directly usable by ML algorithms.

EHR developers also tend to incorporate new features that are driven by federally mandated requirements; a clear return on investment would be needed to support deployment of new AI, Dr. Bur said. Unfortunately, current fee-for-service payment models may actually deter health systems from adopting AI. Under fee-for-service, hospitals bill for each clinical activity and, in the case of an incorrect diagnosis, may perform and bill for follow-up tests and care. This means AI that reduces incorrect diagnoses may actually reduce a health system’s revenue if they adopt it.

Dr. Friedland said adequate funding is another detriment. “Developing meaningful AI for clinical use in otolaryngology will require years, if not decades, of research to develop expert systems,” he said. Some problems in the field can only be identified by those on the front lines. We need research funding to perform this work and to incentivize young physicians to study AI and ML in otolaryngology practice.”

Dr. Chowdhury added that there is a large learning curve needed to truly understand the scope of AI and ML research, as it combines advanced elements of statistics, mathematics, computer science, and probability theory, with which most physicians are unfamiliar. “This creates a barrier to entry that may make it challenging for AI models to gain broader acceptance within the medical community,” he said. “People tend to reject what they don’t understand.”

The small datasets that otolaryngologists are accustomed to investigating in the specialty pose yet another challenge, because ML requires large data sets. To overcome this challenge, Dr. Chowdhury recommended collaborating with others to collect large amounts of high-quality data. In fact, it is probably the only way, given the small size of the otolaryngology specialty. “We also need to collaborate with skilled individuals specializing in AI and ML to incorporate this technology into our field,” he said. “It’s probably unrealistic for most otolaryngologists to have a deep understanding of the technology’s nuances, especially considering how quickly things change. Models and algorithms are often outdated within a year or less, so it takes a lot of effort to stay on the leading edge.”

A Promising Future

Despite challenges, otolaryngologists have many reasons to be optimistic about AI’s future, Dr. Bur said. AI has seen tremendous growth, paralleled by advances in computing power, in the last decades, and all indicators signal that this trend will continue. As CMS and private insurers continue to explore alternative payment models, it is likely that incentives for health systems and EHR developers will shift in favor of technologies—such as AI—with the potential to improve healthcare quality and cost. In launching the AI-driven clinical data registry Reg-ENT, which is designed to harness the power of data to guide the best otolaryngology care, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery is taking an important step to prepare for alternative payment models and increased requirements for quality reporting that will affect reimbursement.

By participating in clinical data registries such as Reg-ENT and by seeking to collaborate with data scientists in developing new AI, otolaryngologists can ensure the field is a pioneer in the development and deployment of AI technologies in clinical practice.

To get more otolaryngologists on board with using AL and ML, Dr. Chowdhury sees general awareness of AI’s potential as the first step. “We hope to have dedicated sessions at upcoming national meetings to talk about and explore AI and ML possibilities, and try to build more collaborations,” he said. For clinicians interested in being actively involved in AI and ML research, he recommended reviewing the principles behind the statistical models like linear regression and logistic regression, as these are often simpler (and better) options for predictive analytics than non-linear models. “With this foundation, it is much easier to understand how ML algorithms work, and their limitations.”

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer based in New Jersey.

Key Points

- While use of artificial intelligence in otolaryngology is in its infancy, the benefits show great promise.

- Current uses of AI in otolaryngology include otoscopy imaging, language processing, and categorizing chronic sinus conditions.

- Despite its potential, AI raises new ethical concerns around patient privacy and safety, data bias, and the physician–patient relationship.