Since the first report in 2008 of the effectiveness of propranolol to treat infantile hemangiomas, its use has grown among physicians who treat these tumors, which arise in 5 to 10 percent of infants (N Engl J Med. 2008;358(24):2649-2651). Among these infants, approximately 10 percent will require treatment to correct functional impairment or prevent lasting cosmetic deformity caused by the hemangioma (N Engl J Med. 1999;341(3):173-181; Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14(3):173-179).

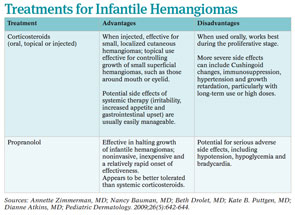

The appeal of propranolol as a treatment choice is its demonstrated efficacy with reported lower side effect profile compared to other treatments, including corticosteroids, which have been the treatment of choice for many years.

To date, data are largely derived from small case studies and retrospective reviews. Propranolol appears to effectively halt growth of infantile hemangiomas and hasten involution with relatively rare side effects of sleepiness, night terrors, bradycardia, hypotension and hypoglycemia. A 2010 literature review of 11 case studies found that infants treated with propranolol for cutaneous, subglottic and oropharyngeal hemangiomas had significant regression, with minimal side effects (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(4):338-342).

Other treatments, mainly systemic steroids, also seem effective, but the risk of side effects appears to be greater, particularly when used over time and in high doses. A study published in May reported that propranolol was effective for 26 hemangiomas of the nose, lips and parotid area, conditions researchers would normally have observed rather than treat with corticosteroid therapy (Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(5):471-478). Given the accumulating data on the efficacy and tolerability of propranolol in this setting, many otolaryngologists are adopting this agent as the first choice of treatment and even expanding the indications to treat these congenital anomalies.

“Propranolol appears to be an effective treatment for infantile hemangiomas and should now be used as a first-line treatment in hemangiomas when intervention is required,” said Annette Zimmerman, MD, assistant doctor of otolaryngology- head and neck surgery at Philipps-University Marburg and University Hospital Giessen and Marburg, in Marburg, Germany, and lead author of the literature review. Dr. Zimmerman emphasized propranolol’s well-documented safety and side effect profile in children based on more than 40 years of clinical use as therapy for infant cardiovascular disease.

Data Limited

Others, however, are voicing the need for more evidence to help physicians determine the true role of propranolol in this setting, given the lack of prospective data comparing the safety profile and efficacy of propranolol with corticosteroids. This call is particularly strong in the U.S., where propranolol is used off label.

Nancy Bauman, MD, a pediatric otolaryngologist at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C., who is among those calling for more evidence, particularly prospective evidence, cites past experience with a drug that everyone thought was safe but that, over time, was shown to be unsafe in infants with hemangiomas.

“Years ago, we were excited about the use of alpha-interferon for treatment of infantile hemangiomas, but several years later our enthusiasm was dampened by its association with spastic diplegia when given to young infants,” she said.

Dr. Bauman thinks that propranolol is an excellent medication for infantile hemangiomas and believes that it is safe but feels that adverse events need to be carefully collected and monitored. “The increasing use of propranolol for treating infantile hemangiomas without first completing phase 2 studies is the natural process of using any medication [that is] available on the market but [is] used for an off-label indication,” she said.

To that end, she and colleagues recently conducted a literature review of all 49 manuscripts published on this topic before September 2010. The review is in press for the Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology and highlights not only the efficacy of propranolol, but also the importance of monitoring and tracking the side effects that occur in 17 percent of patients and can be serious, such as bradycardia, hypotension, hypoglycemia and bronchospasm.

Toxicity

Currently, data from non-prospective studies indicate that propranolol is well tolerated with few frequent side effects. Minor side effects like sleepiness and gastroesophageal reflux made up much of the toxicity reported in the most recently published series of studies by investigators from the University of Arkansas (Laryngoscope. 2010;120(4):676-681). Among the 32 children treated with oral propranolol in that study, 10 had minor side effects, of which somnolence was the most frequent (27.2 percent), followed by gastroesophageal reflux (9.1 percent), respiratory syncytial virus exacerbation (4.5 percent) and rash (4.5 percent).

Although none of the children in the study experienced serious side effects, and hemangiomas improved in 97 percent of participants, with 50 percent achieving an excellent response, lead author Lisa Buckmiller, MD, emphasized that propranolol should not be used lightly in this setting.

“Propranolol is a great medication in our armamentarium for treating hemangiomas,” Dr. Buckmiller said, but she emphasized that “serious side effects like life-threatening bronchospasm and hypoglycemia can occur, and we are discovering more about the medication and its side effects every day.”

Beth Drolet, MD, professor of dermatology and pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, said much more research is needed. “Although there have been over 60 articles describing the use of this medication for treatment of infantile hemangiomas, there is very little data prospectively evaluating the toxicity of this drug in this population,” she said.

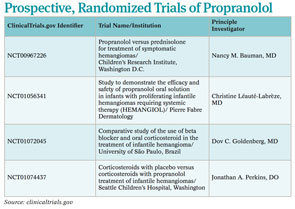

To fill the gap in the evidence on toxicity, a number of prospective, randomized clinical trials are currently recruiting patients to compare propranolol to corticosteroids (See “Prospective, Randomized Trials,” p. 4).

Need for Caution

Despite the lack of prospective data on toxicity, current data already indicate the need for caution when using propranolol in some infants and in specific situations.

Among the children who may be at the highest risk for side effects are the very young. “Physicians need to realize that some infants with infantile hemangiomas are preterm and low birth weight, which may put them at increased risk of side effects,” said Dr. Drolet. She was recently awarded federal funding to design a prospective trial that will compare toxicity and efficacy of prednisolone combined with propranolol and propranolol alone in infants with complicated hemangiomas.

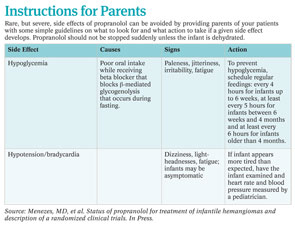

A major and potentially dangerous possible side effect for these young infants is hypoglycemia, the biggest risk factor in infants under six months old, according to Kate B. Puttgen, MD, assistant professor of pediatric dermatology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md., who added that this statement is based on anecdotal data and case studies (J Am Acad Dermatol. [Published online ahead of print May 19, 2011]).

To ensure proper monitoring in her patients, Dr. Puttgen admits most patients under 12 months so that she can monitor them for 48 hours to reach a dosing goal of 2 mg/kg/day divided by 8 hours (0.67 mg/kg/dose). For those infants being treated on an outpatient basis, she doses much more slowly, increasing to a target dose over 10 to 14 days. For all patients, she monitors blood pressure and heart rate until the infant is stable on the drug and also at each follow-up visit.

“Most infants need to be on the drug for six months or more,” she said. “They need to be treated at least until the hemangioma is beyond its natural proliferative phase.”

To prevent hypoglycemia, Dr. Bauman emphasized that physicians must educate parents about the need to keep their infants on a regular feeding schedule. This is particularly important when infants may stop eating because of a viral infection, for example.

“Parents should always be counseled that they need to feed babies on a regular basis, and if the baby is missing a meal for whatever reason, then the propranolol dose should be withheld until the baby resumes eating,” she said.

Other infants in whom propranolol should be used with caution include those with reactive airway disease or heart problems. Dr. Buckmiller recommended not using propranolol in these patients, whereas others suggested that propranolol can be used with caution.

Dianne Atkins, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of Iowa Children’s Hospital in Iowa City, said propranolol has been used extensively and safely in children to treat a number of cardiac problems, such as hypertension, arrhythmias and congenital heart disease. However, she did caution that bradycardia may occur, particularly in premature infants or in those younger than six months, and may require reducing the propranolol dose.

Overall, Dr. Atkins emphasized the need for close monitoring when infants begin treatment. She admits infants younger than six months for at least 24 hours—often 48 hours—to monitor heart rate and blood pressure.

Another group of infants for whom caution is needed are those with PHACE syndrome. (PHACE is an acronym representing posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies, coarctation of the aorta and other cardiac defects and eye abnormalities (Ophthalmology. 1999;106(9):1739-1741).) Dr. Drolet cited a study reporting that about one-third of infants with large infantile hemangiomas of the head and neck have PHACE syndrome, and these infants have a congenital vasculopathy that may put them at higher risk for some of propranolol’s side effects (Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):e418-e426).

Developing Protocols

Questions still remain regarding propranolol’s mechanisms of action, the best dose to use, the best way to start and stop treatment and why some hemangiomas respond better than others, according to Dr. Buckmiller.

Dr. Buckmiller and her colleagues are currently looking at standardizing a protocol they use at their institution. “There are many ways that different institutions administer propranolol, and we need to come to a consensus,” she said. “As we understand more, our protocols change.”

Since the publication of the 2010 paper in which she and her colleagues described their protocol (Laryngoscope. 120(4):676-681), Dr. Buckmiller said that her institution has already made some minor changes to the protocol to ensure maximum safety.

Overall, Dr. Buckmiller recommended that physicians who have scant experience with using propranolol in this setting get help from institutions with more experience or refer their patients to those institutions.

Dr. Atkins also recommended that physicians seek assistance from a pediatrician or pediatric cardiologist before starting therapy on any infant. Dr. Puttgen, for example, said she already routinely obtains a specialty consultation before treating any infant with a history of underlying cardiac or pulmonary disease.

Leave a Reply