Explore This Issue

September 2012Whatever the initial injury—stroke, Bell’s palsy or Ramsay Hunt syndrome, sacrifice of the nerve during tumor resection or traumatic injury—facial paralysis is often psychologically devastating to patients.

Despite an ever-increasing armamentarium of treatment approaches, misconceptions about treatment options and prognoses still exist, said Babak Azizzadeh, MD, FACS, director of the Facial Paralysis Institute in Beverly Hills, Calif. He vividly recalls seeing one patient who had suffered facial paralysis for almost a year, a man whose primary care physician had told him that there was “nothing we can do.”

Otolaryngologists who specialize in diagnosing and treating facial paralysis would like to combat that attitude. Advances in minimally invasive treatment and multidisciplinary approaches to this condition have resulted in restoration of symmetry and function, as well as better quality of life, for those affected.

The Eyes Come First

The most common acute presentation of facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy, thought to result from a polyneuritis of idiopathic etiology. A viral etiology (i.e., herpes simplex type 1, herpes zoster and others) has been suspected to play a role. Many recommend a trial course of steroids and possibly antivirals, although recent evidence has not supported the use of antivirals (N Engl J Med. 2007;357(16):1598-1607). Definitive attention to eye protective measures is imperative.

David Hom, MD, professor of otolaryngology and director of the division of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, teaches an instructional course with a colleague on facial paralysis at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery and emphasized that Bell’s palsy is a diagnosis of exclusion. Clinicians must rule out other causes of the paralysis, which could include stroke, acoustic neuroma, a parotid lesion or even Lyme disease, among other causes. Ravi N. Samy, MD, neurotology fellowship program director at the University of Cincinnati/Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and co-instructor of the course, includes in his complete history questions about outdoor activities to assess the necessity for a Lyme titer; a screening hearing test may lead to a CT or MRI scan to rule out skull base pathology. For example, an imaging study on Dr. Azizzadeh’s patient revealed an acoustic neuroma that was later removed, and the patient made a full recovery.

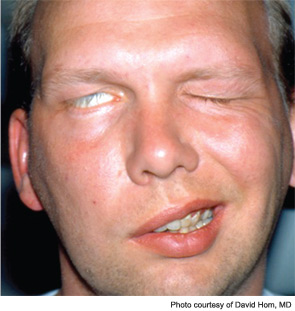

For the majority of Bell’s palsy patients, symptoms resolve within a one- to three-month period. Even during this period, however, the eyes must be protected. Without the ability to close the eye, patients’ corneas become dry, putting them at risk of abrasion and ulceration. Therefore, whatever the cause or prognostic course of the paralysis, noted Dr. Hom, “we always think first of protecting the eyes.” Short-term measures include the use of eye ointments, non-preservative eye drops, transparent moisture eye patches and wraparound sunglasses during the day.

Some patients may benefit from initiating facial massage, said D. Bradley Welling, MD, PhD, chair and professor in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the Wexner Medical Center at The Ohio State University in Columbus. “Massaging the face can cause the muscles to contract and retain tone while waiting for nerve regrowth,” he noted. Others have suggested biofeedback with electrical stimulation, although the evidence is not definitive on its efficacy for hastening recovery. Attention to hair styling and makeup strategies can also de-emphasize asymmetry, according to Dr. Hom. (Patient information, personal grooming ideas and other self-help tips can be accessed at facialnervepalsy.com.)

Temporary or Permanent?

The initial goal is to reinnervate the facial muscles in order to maintain muscle tone. How long clinicians should wait before initiating directed interventions is often debated, said Dr. Welling. At his institution, the approach may be to use electroneuronography (ENoG) to assess nerve function in the acute phase; at six to eight weeks post-presentation, electromyography (EMG) may help assess function. It’s best not to wait beyond one year to initiate grafting procedures, said Dr. Welling, because reinnervation may be compromised. However, he added, “The way we treat facial paralysis includes art as well as science. We need to press forward with good outcomes studies that will help us answer some of these questions about timing more definitively.”

“Getting the nerve to function normally is by far the best indicator of overall good facial mimetic musculature outcome,” said Dr. Samy. In the case of a subset of patients with Bell’s palsy, the data indicate that, ideally, facial nerve decompression via the middle fossa route should be done within 10 to 14 days to ensure the best nerve function for those who meet electrophysiologic criteria using ENoG and EMG (Laryngoscope. 1999;109(8):1177-1788).

“Synkinesis, or aberrant nerve regeneration, is probably the biggest issue for patients who do not have complete resolution of Bell’s palsy,” said Dr. Azizzadeh. Treating the contralateral side with Botox benefits these patients and the 15 percent of Bell’s palsy patients whose symptoms do not completely resolve, said Dr. Samy. Injecting Botox into the contralateral side to weaken the muscles and achieve symmetry must begin with the smallest dose possible, Dr. Azizzadeh advised. “You are injecting muscles, such as the buccinators, that are not the ones commonly injected for cosmetic reasons. So there is an art to this, and Botox does not behave in every patient in the same way.” Dr. Hom agreed: “As with other treatments, you have to tailor the dose to each patient. Give minute strengths to the target antagonistic muscles to try to get a balanced face.” After the first injection, Dr. Hom’s patients return in three weeks, and then at three- to six-month intervals, for additional injections.

Reanimating Facial Nerves and Muscles

If the facial nerve does not begin to function with time or has been sacrificed as part of another procedure, treatment strategies should be tailored to the patient’s circumstances, based on time of nerve injury, state of health, age and functional goals, Dr. Hom said. Travis T. Tollefson, MD, FACS, associate professor in the department of otolaryngology at the University of California-Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, Calif., agreed that a patient-centered approach is key. With head and neck cancer surgery patients likely to have facial nerve sequelae, Dr. Tollefson’s approach is to start conversations about options early. He begins with incremental treatments, such as brow lifting or eyelid loading with gold or platinum, to allow patients to become acclimated to procedures.

If prolonged recovery is anticipated or if permanent paralysis is present in the upper face, Dr. Hom considers either low profile gold or platinum weights to restore the blink response. The procedure, first pioneered by Mark May in the 1990s, revolutionized treatment for the paralyzed eyelid (Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987:113(6):656-660). Before that time, a lateral tarsorrhaphy was the most common technique for permanent protection of the eye. This method impaired the visual field on the lateral gaze, did not give complete eyelid coverage and was not cosmetically attractive. When extensive oncological resection surgery is required, Dr. Hom prefers to wait until the post-surgical swelling has abated to fit his patients with the eyelid weights, although other surgeons may place the weights as part of a respective procedure. He chooses the weights, which range from 0.6 to 2.8 grams, in the clinic, allowing him to tailor them for each patient. In addition, a lower eyelid tightening procedure and a direct brow lift can be beneficial. All of the upper facial procedures can be performed as outpatient procedures, under local anesthesia with intravenous sedation.

Many options also exist for the lower face. “The first choice is to try to directly repair the nerve or use cable nerve grafts,” said Dr. Hom. If this is not possible, then hypoglossal-facial nerve anastomosis or cross-facial nerve grafting can be used as long as the motor end plate of the muscle has not fibrosed. After one year of injury, EMG is helpful to determine the state of the distal facial nerve injury. After one to two years, if nerve repair is not possible, muscle transposition techniques using the temporalis sling can be successfully used for chronic paralysis, taking into consideration the patient’s age, health and personal preferences (Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006:14(4):242-248). More recently, the orthodromic approach for temporalis tendon transfer, which reanimates the lower face without the disadvantage of creating fullness over the zygomatic arch or a concavity at the temporal fossa, has been gaining popularity (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011:145(1):18-23).

For static support of the lower face, a minimally invasive procedure to suspend the corner of the mouth can be achieved by making an incision in the melolabial crease and anchoring a heavy permanent suture to the zygoma periosteum. Under intravenous sedation, this suture can then be tightened by placing the patient in an upright position to tailor the precise pull needed to improve lip competency, with immediate patient feedback, said Dr. Hom.

Like many of his colleagues, including Dr. Azizzadeh, Dr. Tollefson utilizes 3-D video animation to help patients visualize movement deficits and then has them work with physical therapists to teach them biofeedback techniques to retrain muscles (Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2010;18(2):351-356). In his own research, Dr. Tollefson has been investigating electroactive polymer artificial muscle to restore eyelid closure, having completed cadaveric studies and moved on to rodent models (Laryngoscope. 2007;117(11):1907-1911).

Goals of Treatment

During the patient’s recovery, facial nerve rehabilitation and botulinum injection are also very helpful in minimizing unwanted synkinesis. In addition, psychological support is an important part of facial nerve rehabilitation. To comprehensively treat patients with permanent facial paralysis, a long-term commitment to follow-up is needed to maximize their facial function and appearance, because future surgical adjustments after facial reanimation procedures are required to optimize results due to the aging process and healing. Long-term goals are to maximize eye protection, oral competency, facial movement and facial symmetry.

In interacting with his patients, Dr. Samy chooses to emphasize the positive aspects of their recovery, giving them a sense of hope and optimism. For example, one of his patients suffered significant intracranial injuries in addition to facial paralysis as a result of a work-related trauma. Luckily, the patient has no residual cognitive deficits. “I tell him that while he has some minor residual signs of facial palsy, ‘this is just one more step in your recovery, which has gone very well.’ Unfortunately, there is still a sense in the community that there is nothing that can be done for facial paralysis. But there are things that can be done, and patients need to feel that they are listened to.”

Leave a Reply