Explore This Issue

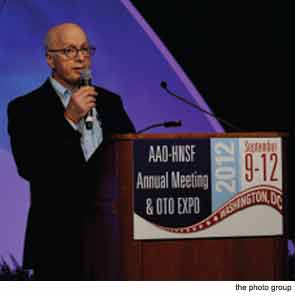

October 2012WASHINGTON—Itzhak Brook, MD, is an adjunct professor of pediatrics at Georgetown University, but when he appeared at the opening ceremony here at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, held Sept. 9–12, he took the stage more as a patient than as a doctor. Dr. Brook, a throat cancer survivor who now speaks with a voice prosthesis, did his best to put the otolaryngologists in the audience in their patients’ shoes—and because he’s a doctor, too, his words carried particular authority.

“In a way, I’m here for many voiceless patients,” said Dr. Brook, who gave the John Conley, MD, Lecture on Medical Ethics at the meeting. He reminded doctors of the deep emotions patients can experience while undergoing diagnosis, treatment and recovery and urged the audience to always keep that in mind, because doctors themselves can act as a patient’s most vital supporter. “Throat cancer or head and neck cancer strikes the most basic needs of a human being: the ability to communicate, eat and interact with others,” said Dr. Brook, “and losing those is really a very devastating experience.”

Dr. Brook told his story in his recently published book, My Voice: A Physician’s Personal Experience with Throat Cancer. The loss of control over his own destiny was one of the more difficult parts of his illness, he said. “I suddenly had to deal with my own mortality. I needed to deal with fear, anxiety and uncertainty of the future. I had to entrust myself in the hands of others to take care of me.”

Just finding the right doctor was stressful, he said. “If you think that I had a hard time, imagine how a lay person has difficulty making the best decision or knowing who is the best physician for them,” he said.

He urged doctors to be honest with their prospective patients. “All I can tell you is to ask yourself, are you the best person to offer the treatment and the surgery for your patient?” he said. “There may be somebody else who may offer better treatment than you.” It’s the natural inclination to want to help, he said. But he advised the physicians to “take a little bit of humility and courage” and to “encourage the patient to get a second opinion and understand the great difficulty the patient faces learning that they have cancer,” he said.

He reminded doctors that some patients might have a better ability to handle the stark truth than others. “I met physicians who were optimistic and some who were pessimistic,” he said. “I prefer the truth, even if it’s not so rosy. Of course, other people may not be able to handle the whole truth.”

Effective Communication

It may be hard for patients to really process and appreciate what doctors tell them about what the experience of a laryngectomy will be like, said Dr. Brook. Doctors told him what he would be dealing with, but whatever they said could not actually prepare him. “When I woke up with tubes, IVs, catheters and no voice, it was so different from everything they told me,” he said. He told the otolaryngologist audience to tell their patients “again and again” about what their experience may be.

“It’s important to tell the patient what to expect in the future,” he said. “Spend more time, allow more time for communication…. Make sure the patient understands what is happening, and understand how difficult it is for the patient to deal with the new reality.”

The most effective communication, though, is nonverbal, he said. At the end of every visit, Dr. Brook’s otolaryngologist would give him a hug. “There is no substitute for the power of a hug,” he said. “Each hug meant more to me than the thousand words he said. This is because I knew he really cared.”

Additionally, depression can be a consequence of the cancer, Dr. Brook said. Head and neck cancer, openly visible to others, leads to one of the highest suicide rates among all cancer types, he said. Having difficulty speaking can keep people “all bottled in,” he said. “You cannot express your feelings and emotions the way you did before—our facial expressions are not really the same,” he said. “Getting the patient on anti-depression medication is very useful in some patients.”

His throat cancer has come with some advantages, he has realized. First, he doesn’t have to wear ties, “which is great, because I never liked them,” he said. He also doesn’t snore anymore. And he said the ordeal has made him a better doctor. “I always cared for people,” he said, “but now I have a greater appreciation to what they actually feel, and that makes me more human and more humble.”

‘Like a Friend’

In another address, guitarist Blue O’Connell told the audience how getting a cochlear implant revived her dream of becoming a professional musician. While she was a serious student studying classical music her hearing degraded. The first realization came when a friend invited her over to listen a piece and O’Connell couldn’t hear the music.

She said the hearing loss, which was brought on by fevers suffered as a complication of mononucleosis in her childhood, somehow didn’t affect her ability to play music, but it did greatly hamper her ability to talk to people. She couldn’t book gigs, and she eventually gave up on her music career and got a job as an office manager. “There I stayed 14 years, alone in a windowless office behind a computer,” she said. “Many days I felt very discouraged.”

But, three years ago, she decided to get a cochlear implant. “I had never been hospitalized before, and what could have been a frightening ordeal turned out to be one of the most touching experiences of my life,” she said. “My surgeon was like a friend to me.”

Now, in her early 50s, she has the best hearing she’s ever had. And she is a professional musician, playing guitar for hospital patients, seniors and young adults with disabilities. “You have removed the obstacles that prevented me from moving forward with my dream,” she told the audience.

Leave a Reply