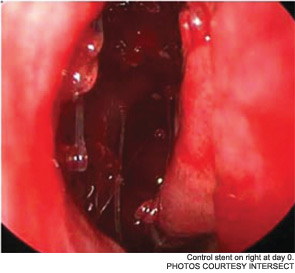

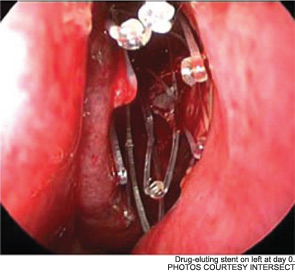

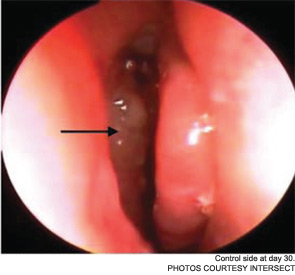

Maintaining sinus patency after functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) has long been an issue; as many as 23 to 47 percent of patients require revision surgery after FESS (Laryngoscope. 1993;103(10):1117-1120; Laryngoscope. 2004;114(5):811-813.) Now, a new drug-eluting, bioabsorbable stent manufactured by Intersect (Palo Alto, Calif.) is being billed as a “breakthrough treatment [that] improves outcomes for sinus surgery,” according to a news release from the company. The device, which received pre-market approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in August, has been studied since 2008. It is currently available in Texas, New York, Philadelphia, New Jersey, Atlanta, Ohio and Kentucky.

Explore This Issue

December 2011But is the drug-eluting stent, called Propel, truly a game-changer, or is it simply another step in the treatment of CRS?

History of Sinus Stenting

“The concept of stenting a sinus at the end of a procedure goes back decades, and countless devices have been proposed and used over the years,” said Martin Citardi, MD, FACS, chair of the department of otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston. “None of them proved themselves to work very well over a period of time.”

Prior to the 1950s, some otolaryngologists placed stents made of latex rubber in the sinus outflow tracts after sinus surgery, said Stephen Freeman, MD, FACS, an otolaryngologist currently in private practice in Carmel, Ind. The problem was that latex often caused tissue reactions, creating scar tissue. By the 1950s and 60s, sinus stents had developed a bad reputation.

Dr. Freeman and others, though, remained intrigued by the possibility of sinus stenting. “In the late 1980s, I would take urinary catheters made out of silicone, trim them [down to] a small tube and place them in the sinuses,” Dr. Freeman said. After one patient’s stent popped out unexpectedly, Dr. Freeman created the bi-flanged sinus stent now known as the Freeman stent.

The device, designed for use in the frontal sinuses, appeared to help maintain sinus patency post-surgery, although stent blockage and build-up of granulation tissue around the stent were noted in clinical studies (Laryngoscope. 2000;110(7);1179-1182). Premature degradation of the plastic tip of the insertion device led to the removal of the Freeman stent from the market for a two-year period; it’s currently back on the market.

Meanwhile, otolaryngologists’ understanding of rhinosinusitis has continued to evolve. “Chronic sinusitis is not a simple plumbing problem,” said David Kennedy, MD, professor of rhinology at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School in Philadelphia. “Just opening up the sinus is rarely a solution to resolving the disease, because there’s often a diffuse inflammatory problem as well.”

Leave a Reply