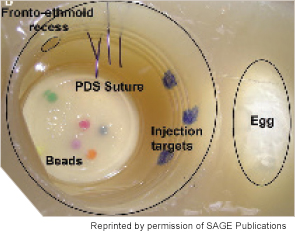

Labeled sinonasal cavity of fully constructed sinus surgery task trainer (left).

Medical simulation, whether it comes in the form of high-tech machines, dummies that act like real patients, or even homemade concoctions made to look like the tympanic membrane, is increasingly a part of the training experience of medical students and residents. In a 2011 survey conducted by the American Association of Medical Colleges, 83 of the 90 medical schools that responded indicated some use of simulation across a five-year span of residency education, and 55 of the 64 teaching hospitals that responded indicated use of simulation.

Explore This Issue

October 2014No figures exist on exactly how many otolaryngology programs are using simulation, but the scientific literature is full of descriptions of simulators that are currently available or under development. One systematic review, for example, describes 13 bronchoscopy simulators, 10 sinus/rhinology simulators, eight oral cavity simulators, eight neck simulators, and even simulators that teach nontechnical skills like teamwork (Int J Surg. 2014;12(2):87-94).

Educators encourage the trend, saying that medical simulation is a way to help residents warm up to working with real-life patients.

“It’s not going to replace actual patients, because eventually you have to finesse your skills with real experiences, but it can help you accelerate the learning curve and do that without direct risk to real patients,” said Ellen Deutsch, MD, FACS, FAAP, director of surgical and peri-operative simulation at the Center for Simulation, Advanced Education, and Innovation at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Dr. Deutsch is also chair of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Surgical Simulation Task Force.

Plus, residents love it. “Especially for the junior residents, it gives them a sense of accomplishment to be able to master these techniques in the lab. They feel more confident and less anxious when they get into the operating room,” said Sonya Malekzadeh, MD, FACS, professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, DC.

Simulation can also extend the teaching of important clinical skills that are sometimes limited because of ACGME work-hour restrictions, said Marvin Fried, MD, chairman of otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Albert Einstein College of Medicine/Montefiore Medical Center in New York, where he’s been working with medical simulation for the past 14 years. “[Residents] feel they learn more from the simulation environment than they do observing or trying to learn from a textbook. It’s more real.”

Most importantly, exposing your students to simulation doesn’t mean overhauling your education program. Here are tips on how to get started:

Leave a Reply