The time for otolaryngologists to adopt electronic health records (EHRs) is now, practice management and information technology experts said at a session at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, held here Sept. 26-29.

More of the Same: Why isn’t otolaryngology becoming more diverse?

As America grows and evolves, its face necessarily changes. Our country rests solidly on the idea that life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness should be available to all. Our collective understanding that access to health care and healthy living are essential to that ideal happiness continues to mature. But while the population becomes more diverse and blended, cultural disparities in health care not only persist, they do not appear to be diminishing. Collectively, African-Americans, Hispanic Americans and Native Americans comprise over one-quarter of our population. Yet, in the year 2000, they made up less than 10 percent of the physician workforce. These numbers dwindle even more when we consider surgical subspecialties.

Your Practice, Your Brand: Top 3 marketing strategies

It’s a common challenge: In a tough economy, do you spend to increase patient revenue or save to keep your practice afloat?

Generation Gap: Combating “fogeyphobia” in the workplace

In an address to the 2009 Combined Otolaryngological Spring Meetings in Las Vegas, neurosurgeon Harry Van Loveren, MD, chair of the department of neurosurgery at the University of South Florida, coined the term “fogeyphobia” to describe a tendency among older doctors to become reluctant to speak out against new surgical tools and techniques, out of fear of being viewed as old-fashioned.

Payment Limbo: Medical societies take on SGR reform

In June, Congress gave physicians relief from the scheduled 21 percent Medicare pay cut, but only until the end of November. The payment patch, which briefly increases reimbursement by 2.2 percent, leaves doctors in limbo.

The Opt-Outs: Otolaryngologists extol the benefits of third-party independence

When describing to the curious the benefits of opting out of both Medicare and private insurance, Gerard J. Gianoli, MD, president of The Ear and Balance Institute in Baton Rouge, La., often recalls one particular example: During one 90-day global period about five years ago, after an eight-hour resection of a skull-based glomus tumor, post-operative ICU care and several days of inpatient care and the usual post-operative office visits, he received a total reimbursement of $500.

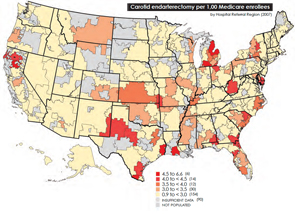

Medicare Battle Heats Up: Geographic Disparities spark look into spending variation

In the wake of this year’s landmark health care reform legislation, one of the most hotly debated topics comes courtesy of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, as politicians, analysts, researchers and physicians grapple over how to resolve the contentious issue of geographical disparities in health care spending.

Anatomy of a Noncompetition Clause: Now’s the time to review your employment contract

A physician who was recently offered a lucrative position with an otolaryngology practice in his community asked me to review his current employment agreement to determine if it contained any prohibitions against accepting the job. His previous employment contract contained a noncompetition clause that, justifiably, caused him and his prospective employer some concern. As it turned out, in his case, and in many others, the noncompetition clause was not as restrictive as it appeared at first glance. The provision was penetrable and my client joined the new practice with a clear conscience that he was not in violation of his previous contract.

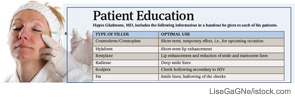

Managing Expectations: Facial plastic surgeons emphasize the limits of injectable fillers

With the availability of noninvasive procedures that use injectable fillers to do the work surgery once monopolized, more people than ever before are seeking the elixir of youth that comes now at the end of a needle rather than a knife.

A New Look at Informed Consent: Recent guidelines prompt patient-centered approach

Otolaryngologists are likely to see some changes in the way informed consent is handled at the hospitals where they perform surgery. Recent changes from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), along with Joint Commission rules, have prompted many hospitals and health systems to get more involved in what previously fell firmly in the physician’s purview.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- …

- 50

- Next Page »