© Amy K. Mitchell / shutterStock.com

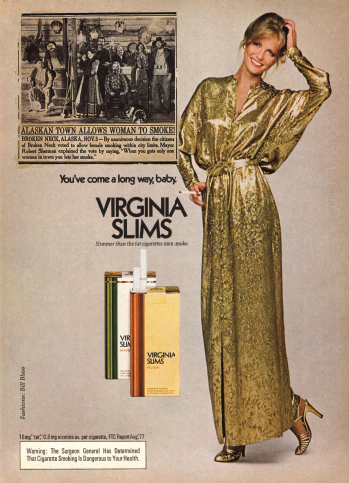

Virginia Slims used to use the tag line, “You’ve come a long way, baby” to highlight the accomplishments of women outside the home; in 1968, apparently, we’d come far enough to have a cigarette brand marketed specifically to us (!). In 2015, the American Association of Medical Colleges reported that 15.8% of the 9,405 practicing otolaryngologists in the U.S. were women, up from 0.3% in 1963. Of 1,472 active otolaryngology residents and fellows in 2015, 36.3% were women.

Explore This Issue

April 2018Yes, we have come a long way. But the road stretches before us. And it seems long and winding.

In Canada, only eight out of 16 (50%) female applicants whose first choice of specialty was otolaryngology matched into it, while 19 out of 25 (76%) male applicants who chose otolaryngology matched into the specialty. The number of women in senior leadership positions is paltry, even accounting for the ‘shadow’ effect between entry into the specialty and the achievement of adequate recognition and accomplishment to reach higher echelons. Even accounting for hours worked, patients seen, and academic productivity, women surgeons are promoted less, paid less, and funded less than their male counterparts (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143:796–802; Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013; 148:215–222). Jonas Johnson, MD, the Eugene N. Meyers, MD, Professor and chair of otolaryngology at the University of Pittsburgh, noted in a 2014 commentary that the proportional representation of female full professors was unchanged over 35 years (J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;43:14). He went on to state that failure to fairly promote women into senior academic positions represents a lost opportunity to benefit from talent of all academic physicians. I agree.

Women in all fields, including otolaryngology, are subjected to the psychic assault of what have become known as ‘manels’—male-only panels at scientific meetings. At this point, with the number of accomplished women in our rolls, the picture of four or six or eight men pontificating from the stage while expert women sit in the audience is more irksome than ever. Now, many men are voting with their feet and refusing to sit on manels, which will only help matters.

On top of this, women otolaryngologists report experiencing and seeing a remarkable amount of ongoing sexual harassment. This harassment is somewhat egalitarian, in that it is perpetrated on physicians both in training and in practice, on medical students, on nurses and operating room and office personnel, and on drug and device representatives.

With less pay, more unpaid and unrecognized work, and near-daily avoidance of some type of harassment, one might assume that women provide suboptimal care. That would be wrong.

Types of Harassment

There are different types of harassment, which need to be identified and addressed.

There is the sexual kind, which includes lewd innuendos, touching, and groping, and goes on up to rape or assault. During my training in the late 1980s and early 1990s, we tried to preempt some of this by dressing to appear as asexual as possible. But we all know that sexual assault is not about sex. It is about power. Thirty-two percent of women otolaryngologists, compared with 5% of men, report personally experiencing sexual harassment (Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:695–702).

There is the psychological kind, which generally can be broken down as follows:

- The reinforcement of a woman’s “impostor syndrome,” where she feels that she somehow doesn’t belong and her boss/institution/colleague/underling/everyone confirms her suspicion;

- The concept of woman as token—“Oh, you’re the woman on the panel/committee/authors list”—not chosen for her accomplishments;

- The assumption that the woman in front of you is a nurse and the man is a doctor, even when the woman is actually cutting on the patient;

- The frequent infiltration into the woman surgeon’s personal life with expressed or implied criticisms of her life choices—married or not, has children or not, has short rather than long hair, is wearing slacks rather than a skirt, and so on;

- The co-opting of a woman’s idea by a man as his, while cutting her out; and

- The assigning of women to nurturing roles even at work, instead of the more “hard-hitting” or scientific work that can lead to recognition and promotion.

There is the disrespectful kind of harassment, which includes co-opting her ideas, decisions that lead to ‘manels,’ decisions that only assign women surgeons to non-surgical topics when they are asked to sit on panels, and gender bias in editorial boards at journals.

Unfortunately, only a small tweak to the headline in the old newsplaper clip included in this 1970s Virginia Slims advertisement, so that it reads “Otolaryngology Allows Women to Lead” and the removal of the cigarette (replaced with a scalpel, an endoscope or a drill), are needed to render this pertinent today.

The Advertising Archives / Alamy Stock Photo

And, of course, there is the monetary kind. Women overall make 74 cents on the white male dollar. Black women? 65 cents. Asian women are “soaring” at 85 cents. The gender pay gap varies geographically within the U.S. In Charleston, S.C., for example, male physicians earn 37% more than female physicians. Black men fare better than women on the whole, but they are not as well paid as white men—an important but different subject matter altogether. Even when a university claims to be female friendly, it is important to read the fine print.

A university may claim that 55% of their department heads and administrators are women. But closer evaluation shows that 94% of the clinical science departments at that university are chaired by men. That can, unfortunately, lead to propagation of poor gender policies.

Not only are we paid less, but women are far more likely than men to run the home and spend greater than 20 hours per week on home care work. Women are more likely to be involved in evening and weekend childcare, and women are far, far more likely to be primarily responsible for the care of a sick child (89% compared with 14%) (Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:695–702). With less pay, more unpaid and unrecognized work, and near-daily avoidance of some type of harassment, one might assume that women provide suboptimal care. That would be wrong.

Women demonstrate better adherence to guidelines and yield greater patient satisfaction. Federal data demonstrated that female hospitalists tended to provide higher-quality care than males. The analysis went so far as to suggest that if all physicians were female, 32,000 fewer Medicare patients might die annually. Patients treated by female surgeons had a decrease in 30-day mortality compared with those treated by males (JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:206–213).

Solidarity

Women across the U.S. and the world are saying, “me too,” and opening up about discrimination and assault. A 2010 article in ENTtoday asked, “The Female Question: Should More Be Done to Increase the Ranks of Female Otolaryngologists?” (ENTtoday, May 2010). I would argue, “Yes,” that women belong in otolaryngology, that diverse teams result in better patient outcomes and clinical and research programs, and that the visibility of women in leadership and mentorship positions will only advance our field.

But, this cannot be accomplished organically. We need our colleagues, male and female, to see what is often smack in front of their faces, to call out what is wrong, and to encourage what is right.

The Virginia Slims ad on p. 8 is from 1970s. Unfortunately, only a small tweak to the headline of the old newspaper clip included in the ad, so that it reads “Otolaryngology Allows Women to Lead” and the removal of the cigarette (replaced with a scalpel, an endoscope or a drill?), are needed to render this pertinent today. Begrudging acceptance is not the same as a wholehearted welcome. It is not universal, but it is the mindset that we need to change. Now. Then we will indeed have come a long way, baby.

Sujana S. Chandrasekhar, MD, is a partner at ENT & Allergy Associates, LLP, director of neurotology at James J. Peters VA Medical Center, clinical professor of otolaryngology at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra-Northwell, and clinical associate professor of otolaryngology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. She is also a member of the ENTtoday Editorial Advisory Board.