A new treatment algorithm for advanced otosclerosis, based on the clinical experience of Dutch investigators and supported by a literature review they conducted, suggests that the window for successful cochlear implantation (CI) in patients with severe disease is narrower than some otolaryngologists may believe (Laryngoscope. 2011;121(9):1935-1941).

According to the authors, once ossification of the middle and inner ear progresses in these patients, the surgical complications that often occur severely limit the chances for a satisfactory outcome. Given that known risk, it’s logical to at least consider performing CI surgery earlier in the disease process in such patients, rather than opting for stapes surgery or hearing aids and follow-up, according to Paul Merkus, MD, PhD, associate professor of otolaryngology and neurotology and a member of the VU University Medical Center Cochlear Implant team in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

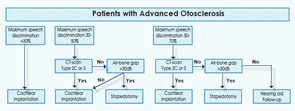

The algorithm divides patients into three groups based on audiometry testing: those with maximum speech determination (SD) scores of less than 30 percent, 30 percent to 50 percent and 50 percent to 70 percent. Based on two other key findings, CT scans of the middle ear and the extent of the air-bone gap (ABG), patients are treated with one of those three primary interventions (Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1935-1941).

For example, patients with SD scores of less than 30 percent often suffer from severe sensorineural hearing loss, Dr. Merkus noted. As his literature review showed, he pointed out, the most effective therapeutic intervention for these patients is CI, “because stapedotomy does not overcome the sensorineural component.”

In patients with SD scores between 30 percent and 50 percent, he added, the algorithm recommends either stapedectomy or CI, depending largely on CT scan results. If those scans show that patients have severe retrofenestral otosclerosis, “CI is the better option” because of the very favorable hearing results that can be achieved, Dr. Merkus said. If the CT scan shows less cochlear involvement, “the ABG should guide the surgeon.” If the ABG is 30 decibels or more, stapedotomy is “a cost-effective option, with good chances of improvement of hearing,” Dr. Merkus said. If the results of stapes surgery in such patients are unsatisfactory at any point in time, he noted, patients can still be treated with a CI. If the ABG is 30 db or less, CI is the preferred option because, in this group, “stapedotomy yields insufficient improvement of hearing.”

Dr. Merkus and his colleagues have already used these patient selection criteria for several years in their clinic. “It’s a bit backward in terms of how research is usually done, but we wanted to know if our approach, and the clinical successes we were having with it, was actually supported by data, so that’s why we conducted the literature search that has resulted in the algorithm in our report,” he told ENT Today.

Based on the literature search, Dr. Merkus said, he believes that there is evidence to support performing a CI in some patients with maximum SD scores of between 50 percent and 70 percent, a speech score that most cochlear implant teams consider too high for CI. In such cases, he explained, the extent of the patient’s disease as shown on CT scan needs to be taken into account. If severe bone remodeling is already present (Type 2C or 3), further progression of hearing loss may be anticipated, and delaying cochlear implantation could diminish the chances of a full electrode insertion.

“We believe that extensive cochlear involvement, as shown by the CT scan, brings with it the risk for impending cochlear obliteration,” Dr. Merkus said. “This may constitute an indication for CI because speech perception and the chances for successful cochlear implantation will diminish further with time.”

Overall, the literature search showed that CI yielded improved hearing in 100 percent of patients, with SD scores ranging from 45 to 98 percent, depending on the hearing test used. With stapedectomy, in contrast, results were poorer: Hearing improved in 46 to 100 percent of patients, with SD scores of between 38 and 75 percent.

In another nod to CI, two of the studies included in the literature review that directly compared stapedectomy and CI described significantly better performance in patients who underwent implantation. “In general, improvements in hearing and speech perception seemed to be better after CI than after stapedotomy,” Dr. Merkus said.

The risk for complications when CI surgery is done in advanced cases is also supported by the literature, Dr. Merkus added. “Many studies show that fenestral and basal turn ossification, the necessity for extra drilling, partial electrode insertion and post-operative facial nerve stimulation do occur in severe disease,” he said.

Reimbursement a Concern

Jennifer Smullen, MD, an instructor of at Harvard Medical School who practices at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston, said reimbursement is a problem for CIs done in patients with SD scores of 50 percent to 70 percent. “Medicare won’t pay for anything above 40 percent, and private payers usually follow suit” with that restriction, she told ENT Today. “That’s a huge issue: CI is an extremely expensive surgery, not just in terms of up-front costs” but also post-surgery costs, such as those associated with programming the processor and other services provided by audiologists, she noted.

But reimbursement isn’t the only issue Dr. Smullen said she has with the Dutch otologists’ desire to push CI a bit earlier in the disease process. “I can see how that ‘window of opportunity’ they point to can be construed as a powerful argument for doing CIs earlier,” she said. “But a main part of their rationale for that approach, the idea that otosclerosis always progresses in severity, is flawed. Sometimes the disease remains stable for long periods of time. Also, data suggest that bisphosphonate therapy can actually halt or slow the disease process.”

Dr. Smullen cited an additional caveat regarding the algorithm in the Dutch paper. Using CT scans and hearing tests to assess patients’ disease progression and need for a particular type of surgery “is a reasonable approach,” she said. “The problem is that they don’t discuss nearly enough the limitations of those hearing tests in giving a true picture of the extent and quality of a patient’s hearing.”

When done correctly, she explained, hearing evaluations give the clinician a picture of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss, both of which can be present in a patient with advanced otosclerosis. Knowing how much of each type is key, Dr. Smullen said, because that determination roughly guides surgical choice: Stapedectomy is used to treat conductive hearing loss, while CI is used for sensorineural hearing loss.

“But you have to test at a high enough decibel level to get a true picture of SD: the ability of the patient to understand words in a sentence,” Dr. Smullen said. “And it’s unclear from their methodology whether the studies they cite, or their clinical experience, takes that into account.”

Dr. Smullen said there are two solutions to this dilemma, and one is “amazingly simple: You communicate with the patient with an ear trumpet. If you talk in a loud voice, you can talk louder than the standard testing equipment that is often used to assess these patients, and if a patient can understand you, that indicates they have a reasonable level of speech discrimination. It’s old school, but it helps us stay true to an important tenet of otology: If you can save a naturally hearing ear and avoid a CI, you do that. And stapedectomy still gives you a naturally hearing ear, whereas CI does not.”

Dr. Smullen said the surgeons in her department always opt for stapedectomy first. “If you do that and the hearing hasn’t improved sufficiently, you haven’t lost anything, you can still go on to a CI,” she said. Stapes surgery, she added, “is a quick, inexpensive outpatient procedure that really needs to be carefully considered for these patients before going to implantation.”

Can stapes surgery—a technique that hasn’t changed fundamentally in 20 years, according to Dr. Smullen—really be the first option for many patients with severe otosclerosis? “I do cochlear implants on a weekly basis, so I am fully capable and willing to recommend implants if I feel they are warranted,” she said. “But the big gun is just not always the best choice.”

Dr. Merkus said he agrees that “going with stapes surgery first is the prudent thing to do for many patients with advanced otosclerosis,” adding that the algorithm supports that approach for selected patients. But he stressed that in rare cases of severe bone remodeling, “it is not advised to perform a stapedotomy, because by postponing CI surgery, you could be creating a very difficult CI surgery in future as the bone remodeling continues.”

David S. Haynes, MD, FACS, professor of otolaryngology, neurosurgery, and hearing and speech sciences at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn., said the algorithm developed by Dr. Merkus and his colleagues “is a reasonable approach; diagnosing and staging advanced otosclerosis can be extremely difficult, so a systematic method for doing that is welcome, especially in the absence of any consensus guidelines on how to manage these patients.”

With regard to the CT component of the algorithm, “they are correct in relying on those findings to guide their interventions,” Dr. Haynes said. “But I would add a caveat here: CT scans don’t always give you the whole story with these patients; it can underpredict disease progression. That’s why we sometimes order an MRI, which gives a more complete picture of what’s going on. In fact, it sometimes will allow us to choose the better ear for our surgery of choice in a particular patient.”

Dr. Haynes echoed Dr. Smullen’s point that aggressive efforts should be taken to preserve a patient’s natural hearing. “That’s why when we perform a CI, we do a round-window insertion and use ‘soft surgery,’ which is a minimally invasive approach to implantation,” he said.

Because of such refinements to CI, “the trend in many clinics over the past 15 years is to rely more on the technology of CI to provide hearing to a wider range of patients, as opposed to stapedectomy. In fact, implant technology has progressed to the point where, along with our abilities to fine-tune the programming of the CI processor, the implant technology can override what we can provide with stapes surgery alone in these cases of far-advanced cochlear otosclerosis.”

That’s not to say that CI surgery should be pushed too far, Dr. Haynes stressed. “In patients with very good word scores, you have to be more conservative: They have too much residual hearing to really be considered for implants.”

—Jennifer Smullen, MD

Lit Review and Algorithm Not a Good Mix

Michael Ruckenstein, MD, professor of otorhinolaryngology: head and neck surgery at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, agrees that stapes surgery is a viable option when patients have stronger SD scores, specifically, equal to or greater than 70 percent. Such scores suggest that the patient has significant preservation of speech discrimination, “and it’s reasonable to use that as an indication that there is significant cochlear reserve present.” In such patients, “a primary or revision stapedectomy that preserves some of that function would be a good first intervention.”

But Dr. Ruckenstein expressed some reservations about the algorithm developed by Merkus and colleagues. “I’m just not sure CT scans correlated strongly enough with surgical outcomes” to give the scans so much weight in the decision tree. “Speech discrimination scores are a better guidepost,” he said. Additionally, the algorithm and literature review “don’t really mesh well. I don’t see anything in the data they cite that truly validates the steps they included,” he added. “It’s a well-done lit review, with useful information on the results of stapes surgery and CI. But I don’t think it supports their stepwise approach.”

Dr. Merkus acknowledged that his team needs to conduct further research in order to fully assess the merits of the algorithm in clinical practice. “That’s actually the next phase of our investigation,” he said.

“Our stepwise approach in itself has not yet been investigated by others, so there is no literature that directly supports the flowchart,” Dr. Merkus acknowledged. Additionally, “we agree with Dr. Ruckenstein that there is no consensus on exact cut-off points in the current literature for audiological performance nor for disease extension as seen on CT scan.

We have used the available literature on the outcome of stapedotomy and cochlear implants in otosclerosis of various degrees of severity in order to come to a reasonable strategy.

We feel that the systematic review does support the choices that are made in the algorithm. However, our approach can only really be validated by a prospective validation study, which is currently being conducted.”

And lest anyone conclude from his paper that CI is pushed heavily at his clinic in all patients with advanced otosclerosis, “that is definitely not the case,” Dr. Merkus said. “For example, when we have a patient who has around a 50 percent speech performance and has a 40 db air-bone gap and is not doing well with hearing aids, we do need to offer them something else. Yes, they would be within the criteria for CI, but we would counsel such a patient that stapes surgery is a better first choice,” he said.

Stapedectomy Not a Slam-Dunk

Alan G. Micco, MD, associate professor and program director of otolaryngology head and neck surgery at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, also advocates stapes surgery in patients whose SD scores are in the 50 percent to 70 percent range. But he cautioned that stapedectomy is not necessarily as easy as the paper written by Merkus and colleauges, or many otologic surgeons, suggest. In fact, this is a procedure that is now only routinely done by fellowship-trained surgeons in the United States, he noted. And, according to a recent study conducted by Dr. Ruckenstein (Laryngoscope. 2008;118(7):1224-1227), there is a growing gap in the number of surgeons who can perform the procedure.

In the 1970s, only 10 percent of graduating surgeons indicated that they had never performed stapedectomies. By the 2000s, that number has soared to 90 percent (P<0.001).

Cochlear implants can also be problematic, Dr. Micco stressed. “There’s a significant amount of drilling that may be involved, and that can cause problems such as facial nerve stimulation,” he told ENT Today. “I do lots of these procedures, and it does happen. Sometimes the audiologist can program the stimulation out, but sometimes you may have to turn off half of the channels. That’s not ideal.” (In the literature review by Merkus and colleagues, the incidence of facial nerve stimulation ranged between 0 percent in a study of 20 patients [Am J Otol. 1990;11(3):196-200] to 75 percent in a study of four patients [Am J Otol. 1998;19(2):163-169]. In the largest study cited, of 53 patients, the incidence of the surgical complication was 38 percent [Otol Neurotol. 2004;25(6):943-952].)

Dr. Micco said that the algorithm developed by the Dutch team “makes some sense,” but its lack of any mention of MRI “is a major omission.” Often, he said, a CT scan will suggest that a patient is a good candidate for CI, “and then you go in and immediately see much more ossification than you had expected, and lots of additional drilling, with its attendant sequelae, is needed. So I’d recommend that you do MRI in cases where you really need the most diagnostic information.”

Dr. Merkus agreed that there is a role for MRI in these patients. Specifically, he recommends that an MRI be performed before planning a CI in all patients who have conditions that increase their risk for cochlear ossification, including meningitis, head trauma, autoimmune inner ear disease and otosclerosis.

Although ENT surgeons may debate the finer points of how best to diagnose and stage patients with advanced otosclerosis, the overall approach of his algorithm “is sound,” Dr. Merkus said. “By focusing on three key parameters, speech performance, CT classification and the extent of the air-bone gap, this tool can guide the surgeon towards the best treatment strategy for patients with this challenging condition,” he added.

Leave a Reply