Medical literature documenting human sleep disturbances dates back centuries, usually in the form of self-reported experiences from patients and their sleep mates. However, the recognition of sleep medicine as its own field is generally traced to the not-so-distant past: the 1970s, when disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) first became clearly defined, and polysomnography became the standard clinical test.

Explore This Issue

December 2020The conversation about which medical specialists are best suited to treat patients with sleep disorders evolved even more recently. Sleep medicine was initially considered the purview of pulmonologists, to whom patients were referred by their general medicine practitioners. Over the years, however, as the complexities of sleep disorder cases became more apparent, so too did the multidisciplinary nature of sleep medicine as a practice. In 2007, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) launched a conjoint American Board of Sleep Medicine (ABSM) that included the American Boards of Internal Medicine, Family Practice, Pediatrics, Psychiatry and Neurology, Anesthesiology, and Otolaryngology (changed in 2017 to “Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery”).

Requirements for otolaryngologists who wish to become dual boarded in sleep medicine have become more stringent in recent years. The American Board of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (ABOHNS) dictates that otolaryngologists with a valid certificate and license in otolaryngology who wish to achieve certification in sleep medicine must complete 12 months of sleep medicine fellowship training in an ACGME-accredited program, wherein they achieve ACGME-established training experience that includes clinical performance and ability to interpret a range of sleep-related diagnostic tests. Finally, candidates must also perform successfully on the ABOHNS Sleep Medicine Certification Examination. (It should be noted that, because the ACGME-accredited, 12-month fellowship requirement was enacted in 2012, many of today’s dual-boarded otolaryngologists earned their sleep medicine certification through previously accepted paths.)

Given the considerable commitment that current requirements for subcertification represent, how worthwhile is it for otolaryngologists to dual board in sleep medicine? So far, those who have chosen this path are few and far between. However, given that an estimated 50 to 70 million people in the U.S. are reported to have some type of sleep disorder—and that number is expected to increase—the personal and professional rewards of doubling up might be worth the investment.

Determining how surgery may be part of an integrated treatment isn’t something you can easily do with just one of those two hats on. It comes down to knowing how to integrate the care of the complex patient. —B. Tucker Woodson, MD

The Draw of Sleep Medicine

Otolaryngologists who dual board in sleep medicine arrived at their decision at different points in their careers. Christine H. Heubi, MD, assistant professor in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and a dual-boarded otolaryngologist who practices in the divisions of pediatric otolaryngology–head and neck surgery and pulmonary medicine at the Sleep Disorders Center at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), solidified her career trajectory prior to medical school while serving as a research assistant.

“I worked on a project entitled, ‘ENT manifestations of children with Down syndrome,’ with Dr. Sally Shott. I participated in an informal multidisciplinary group of specialists where we reviewed complex cases of obstructive sleep apnea in children and was fascinated by the different approaches to care and the variety of management modalities,” she said.

Following her one-year sleep medicine fellowship, Dr. Heubi completed a two-year fellowship in pediatric otolaryngology at CCHMC. “As I went through my ENT training, I found that my experience had an impact on how I approached patients with sleep abnormalities, and I pursued sleep training so that I could offer patients medical and surgical management not only of OSA, but of other sleep disorders,” she said.

Mas Takashima, MD, professor and chair of the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery for Houston Methodist Hospital System at Texas Medical Center, was first drawn to sleep medicine during his residency. “There was nothing more dissatisfying than operating on OSA patients,” he recalled. “We didn’t have good diagnostic tests identifying the site of obstruction. The surgery that we performed was just a uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), which was effective only 40% of the time.” Dr. Takashima wanted to learn more. “Even though I was an otolaryngologist, I never felt that it was appropriate that I was considered an ‘expert’ in the field of sleep surgery,” he said. “I wanted to immerse myself in the medicine of sleep disorders, along with the potential nonsurgical and surgical cures.”

Long recognized in the field of OSA, dual-boarded otolaryngologist and sleep medicine specialist B. Tucker Woodson, MD, professor and chief of the division of sleep medicine and surgery, department of otolaryngology, at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, started out in the early 1990s, before board certification was available. “I’d come out of [Detroit-based] Henry Ford Hospital, which had one of the early programs involving sleep apnea and sleep medicine,” he said. Over time, Dr. Woodson realized that he was seeing a lot of patients who “really needed people with an orientation and understanding of the upper airway anatomy and physiology, and different modalities of treatment. I found that having that double level of expertise was really necessary,” he explained. “I didn’t start out deciding to be board-certified; it just sort of evolved.”

One practical aspect to becoming subcertified in sleep medicine is the addition of reimbursement for reading sleep studies, which Dr. Woodson acknowledges is a benefit of board certification. “It’s still a part—I had around 15 or 20 studies that I read today,” he said. “But for me, the advantage is more about integrating all of the information I gained from the clinical care experience.”

“Your practice goals and interests will determine whether achieving subcertification in sleep medicine will advance your career,” added Pell Ann Wardrop, MD, who began seeing sleep patients at a local hospital sleep clinic in 1999 as part of her general otolaryngology practice. “I entered private practice at a multispecialty clinic and was drawn to adult and pediatric patients with sleep-disordered breathing,” she said. Dr. Wardrop became dual boarded in 2003 and is currently medical director at CHI Saint Joseph Health Sleep Care Center in Lexington, Ky. “A certification in sleep medicine allows you serve as a medical director, to read sleep studies, and to practice within an accredited sleep center,” she explained.

Eric J. Kezirian, MD, MPH, professor and vice chair at the University of Southern California Caruso Department of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery at the Keck School of Medicine of USC in Los Angeles, who became dual boarded in 2009, cited two main categories of benefits to sleep medicine board certification: clinical scope of practice and the simple certification itself. “Sleep medicine board allows one to practice sleep medicine—especially activities such as interpretation of sleep studies—in a sleep center certified by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, without any questions raised,” he said. “In my own career, I never really wanted to be reading sleep studies. However, I did want to indicate that I possessed a similar core body of knowledge as my colleagues in sleep medicine.”

The Complex Sleep Patient

Otolaryngologists who dual board in sleep medicine already have an obvious advantage in working with sleep-disordered patients: They’re otolaryngologists. “The etiology of sleep-disordered breathing is found in the airway, and otolaryngologists are the only specialists trained in the evaluation and treatment of the airway,” Dr. Wardrop said. “Our training allows us to address anatomic issues that affect the successful treatment of our patients. Some patients have issues, such as nasal obstruction, that preclude CPAP compliance. Many patients are intolerant of CPAP or prefer a surgical approach to their issue that will free them from the need to wear CPAP. We offer treatment options that patients need and demand.”

Dual-boarded otolaryngologists also view their training in sleep medicine as an essential piece of the diagnostic and treatment puzzle when dealing with disorders. “My sleep medicine training allows me to give my patients a more comprehensive approach to their care,” said Dr. Heubi. “Instead of focusing only on what surgeries I can offer, I can evaluate and manage poor sleep architecture, circadian rhythm disorders, parasomnias, periodic limb movements, narcolepsy, and insomnia. I can read polysomnograms, which in turn helps me better understand the pathophysiology of sleep disorders. I have a depth of sleep knowledge that goes beyond what’s obtained in otolaryngology training.”

Dr. Takashima believes that advanced sleep training is invaluable for otolaryngologists who plan to treat the more complex sleep patient, especially those with OSA. “In order to be an expert in treating patients with OSA, we should know more about the pathophysiology of this disease rather than just be a ‘technician’ doing the surgery,” he said. “There are many nuances of a sleep study that can be analyzed, such as sleep position, to treat patients. Assessing the adequacy of a polysomnography is also important.”

Patients with OSA who aren’t CPAP compliant may require simple machine titration, but often the problem is more complex and multifaceted. Dr. Woodson sees many such patients and reports relatively few whose only problem is sleep apnea. “Often, we find ourselves trying to integrate treatment for a patient who has multiple sleep disorders—sometimes multiple complex sleep disorders,” he said. “Today I saw an elderly gentleman with apnea of greater than 60 events per hour, with predominantly central apnea but also some obstruction. He has a profound but asymptomatic nasal septal deviation and is failing CPAP. In his case, we could be looking at everything from a phrenic nerve neurostimulator implant and trying to address his nasal airway with one of the more complicated CPAP devices, to other interventions, such as positional therapy and addressing underlying medical conditions such as heart failure.

“Complex patients may have a combination of sleep disorders, such as narcolepsy and sleep apnea, or central sleep apnea and insomnia,” Dr. Woodson continued. “Determining how surgery may be part of an integrated treatment isn’t something you can easily do with just one of those two hats on. It comes down to knowing how to integrate the care of the complex patient.”

A Question of Collaboration

Working within a sleep clinic, otolaryngologists have the opportunity to contribute their expertise in a multidisciplinary setting. “The team at a center for sleep-disordered breathing typically includes neurology, pulmonology, oral and maxillofacial surgery, otolaryngology, and a sleep hygienist (sleep psychologist),” explained Dr. Takashima. “Having a robust center enables the trial of various treatment modalities specifically suited to the patient. For example, if the sleep disorder is more positional and verified by drug-induced sleep endoscopy [DISE], a dental appliance may be appropriate. Or the sleep disturbance can be more anxiety-related, which would be better treated by the sleep psychologist.”

Because sleep medicine is a newer, evolving field, there’s a need for more sleep physicians of diverse training backgrounds to provide quality care and high-level research, and improve outcomes. —Christine H. Heubi, MD

The potential for collaboration in the sleep arena extends far beyond the sleep centers themselves. Practitioners from different fields who have gone through sleep medicine training share a common experience that helps lay the groundwork for working together. “I find my interactions with sleep colleagues in other disciplines to be incredibly rewarding,” said Dr. Heubi, who collaborates with a team at CCHMC’s Upper Airway Center to manage and treat complex sleep disorders. “Each of us brings a different spin or perspective that would be lost if we all had the same background. It truly is the interplay between each of our disciplines that allows us to successfully manage our patients. Because sleep medicine is a newer, evolving field, there’s a need for more sleep physicians of diverse training backgrounds to provide quality care and high-level research, and improve outcomes.”

The collaborative process plays out in various ways. For example, Dr. Wardrop said that the management of patients with the hypoglossal nerve implant involves a multidisciplinary team, and that the evaluation and management of sleep-disordered breathing in pediatrics is often completed by otolaryngologists.

Patient referrals are also a collaborative byproduct of the sleep specialty. “Referring physicians are aware of my interest in OSA, and they appreciate the extra training that went into obtaining board certification,” said Dr. Takashima. “They’re happy that we as otolaryngologists aren’t just recommending UPPP on all of the patients they refer to us. Diagnostic tests such as DISE and robotic base-of-tongue resections add more scientific rationale for the surgical treatment we do.”

By all accounts, however, collaboration among dual-boarded specialists in the field could be much improved. “Overall, the sleep medicine community hasn’t always welcomed otolaryngologists, or a surgical approach to sleep apnea,” said Dr. Wardrop.

Dr. Woodson agreed. “Collaboration seems to be on a case-by-case basis,” he said. “We do collaborate very well with a large number of people in these other specialties, but I’d say that globally there’s certainly room for a lot more collaboration.”

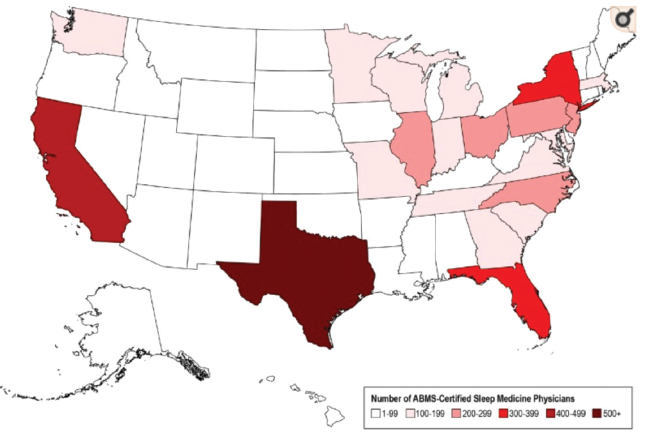

Board-Certified Sleep Medicine Physicians in the U.S.

Heat map of the geographic distribution of American Board of Medical Specialties board-certified sleep medicine physicians across the United States.

Original publication in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine; copyright American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Used with permission. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.6406

The State of Sleep

Otolaryngology residents and clinicians who are thinking about dual boarding in sleep medicine have several factors to consider. As noted earlier, getting certified isn’t as simple as it used to be. Moreover, the number of ACGME-accredited fellowship programs is limited. “There are currently only 180 certified fellowship positions in sleep medicine at 84 centers in the U.S.,” said Dr. Wardrop. “Also, most sleep surgery programs for otolaryngologists aren’t accredited for the purpose of board certification, and most sleep medicine fellowships provide no surgical training.”

Still, there are some compelling reasons to consider taking the leap. First, there’s no shortage of patients, as sleep disorder cases are on the rise, and it’s estimated by the American Sleep Apnea Association that a large majority of sleep-disordered breathing cases have yet to be diagnosed.

Second, it’s becoming increasingly clear that CPAP isn’t a panacea treatment for patients with OSA. “The era of the single-modality treatment for sleep-disordered breathing is changing,” said Dr. Woodson. “Even in medical fields, [physicians] are becoming much more aware of multiple therapies, and even multimodality therapies, as well as a number of surgical procedures.” He cited a recent randomized trial conducted in Australia indicating that multilevel soft-tissue surgeries can be successful in patients who have failed CPAP (JAMA. 2020;324:1168-1179). “So I think there’s more of a role for the subspecialist surgeon to be involved in this disease.”

Looking forward, Dr. Wardrop sees a “looming shortage” of trained sleep medicine practitioners, as many of those who were certified years ago reach retirement age. “I think we’re about to run into a crunch because there aren’t a lot of doctors coming through the pipeline,” she said. Although dual boarding isn’t right for everyone, this scenario just might represent an opportunity too good to pass up.

Linda Kossoff is a freelance medical writer based in Woodland Hills.