To achieve successful patient-centered care, patients and physicians need to understand each other. Physicians need to recognize the specific needs of each patient in the context of medical protocols and standards of care and clearly convey the needed information for shared decision-making. Patients need to understand the meanings of common medical terms, what a diagnosis means, how to weigh the benefits and risks of treatment, and the importance of treatment compliance; in other words, they need to understand a language that may be as natural as breathing to a physician, but may be as impenetrable as a foreign language to a patient.

Explore This Issue

May 2019For some patients, it may literally be another language. Adding to the challenges of talking to patients about their health are the changing demographics in the US, which require physicians to attend to language barriers and different cultural norms based on religion, age, gender, sexual identity, and race that influence how patients hear and act on information conveyed in the clinic.

All of this can be defined as health literacy, a concept that has generated considerable attention for the last decade or so. And yet, studies show that health literacy among patients remains low, and physicians are often unaware of this fact. For otolaryngologists, the paucity of data looking at health literacy is testimony to the lack of attention given to this important issue that permeates all of clinical care. “Few studies address health literacy in otolaryngology patients,” said Uchechukwu Megwalu, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of otolaryngology/head and neck surgery, Stanford University School of Medicine in California. “Consequently, it is not a topic that many otolaryngologists are familiar with.”

It is a topic, however, that is not going away. Low or limited health literacy is linked to poorer health outcomes—particularly in chronic diseases—as well as poor medication adherence, reduced quality of life, increased hospital admission rates, and increased

mortality risk. Not only is this bad for patients, it is challenging to physicians who are increasingly practicing in healthcare systems evolving toward value-based care models that use quality measures to rate physician performance and set reimbursement rates.

If doctors don’t realize there is something wrong and don’t know why they are not getting good patient outcomes, they may not be aware that the patient doesn’t understand them. —Lisa Perry-Gilkes, MD

“Health illiteracy is an impediment to healthcare,” said Lisa Perry-Gilkes, MD, an otolaryngologist with Polaris Medical Group, Emory Healthcare Network in Atlanta. “If doctors don’t realize there is something wrong and don’t know why they are not getting good patient outcomes, they may not be aware that the patient doesn’t understand them.”

What Physicians Say vs. What Patients Hear

Providing an example of how patients hear, Dr. Perry-Gilkes recalled a patient who came to the clinic wanting her to “equal my librium” not understanding what “equilibrium” meant during a previous visit. This highlights what patients who are not familiar with medical terms may hear in the clinic. When issues get more complicated—for example, when patients are signing informed consent prior to surgery or following medication instructions—not understanding the information conveyed can have life-altering consequences, from increased complications leading to hospitalizations to increased mortality. For physicians, legal challenges and lower quality metrics could be the fallout (Health Affairs. April 4, 2019. Available online).

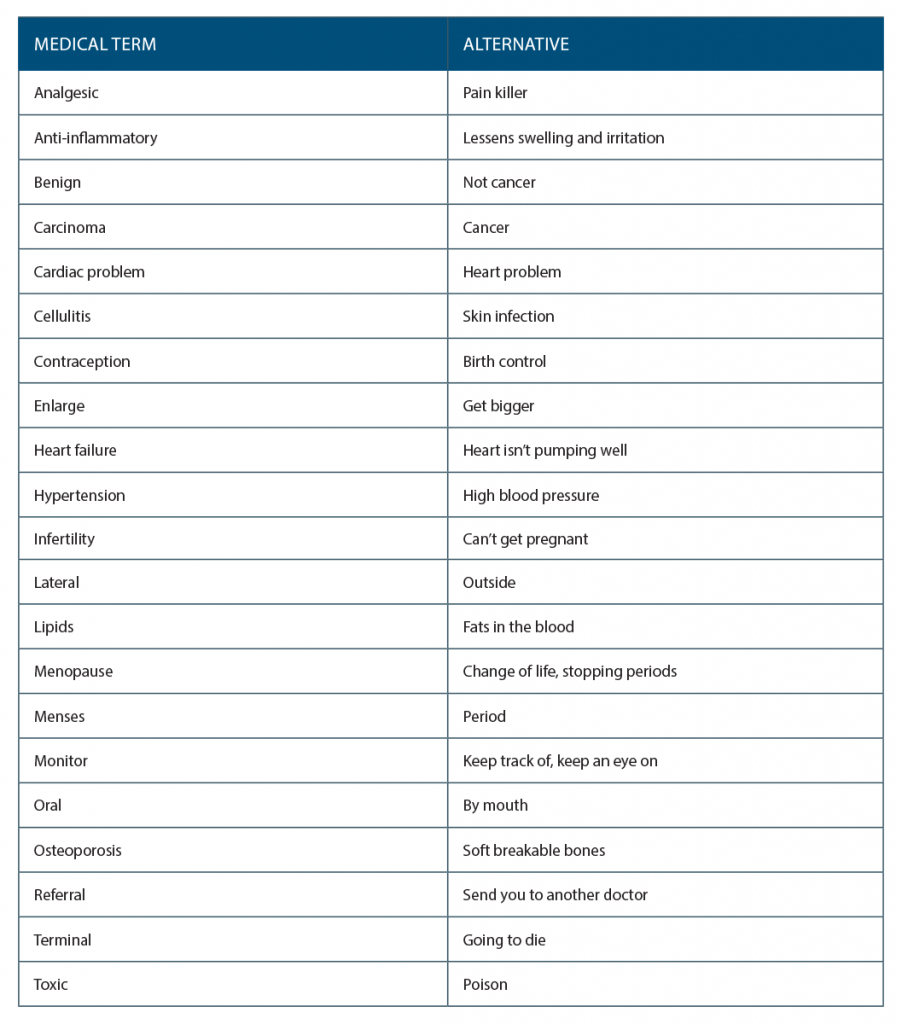

In a 2018 article she wrote on health literacy, Dr. Perry-Gilkes provided examples of simple words physicians can use instead of common medical terms likely to be too difficult for many patients to understand (See “Talking to Patients Using Common Alternatives to Medical Terms,” right) (Atlanta Med. 2018;89:6–8).

In the article, she also described a “teach-back” technique to make sure patients are hearing what the physician is saying. Instead of asking patients if they “understand” what is said, ask them to explain back to you or demonstrate how they will follow, for example, recommendations or a treatment plan. If the patient can’t do this, repeat the information using simpler terms or explain it to a family member or companion.

Ryan Brown, MD, an otolaryngologist–head and neck surgeon at Kaiser Permanente in Denver, also emphasized the need to use simple language and include family members in discussions about treatment. “One of the most important things [to improve health literacy] is just to have good communication with patients and keep terms as simple as possible,” he said.

At Kaiser Permanente, he said, physicians are taught how to deliver medical instructions to patients through training that includes role playing. “Having that process helps to bring it down to the patient level instead of using words that are hard for patients to understand,” he said.

He also stressed the importance of including family members, which is particularly crucial when talking to patients from cultures in which, for example, a husband may need to give his blessing for a treatment his wife needs. “Obviously we’re treating the patient,” he said, “but in some cultures it is all about family.”

Nicole Leigh Aaronson, MD, clinical assistant professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, the lead author of one of the few studies that have looked at health literacy in otolaryngology, also highlighted the need to encourage patients to ask questions and have them reiterate what they hear the clinician telling them (Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;113:252–259). “We definitely see people who have heard things but who don’t remember them, so I think [this] may be one of the best techniques to impart information and avoid complications and risk misunderstanding,” she said, adding that providing small amounts of information at a time is critical to avoid overwhelming patients.

In her study, Dr. Aaronson and colleagues reviewed the research on health literacy in pediatric otolaryngology published between 1950 and the present and found three main areas of research: readability of patient materials, patient recall after informed consent, and attempts at improving patient education. Their data showed that much of the information imparted to patients and families is not meeting literacy needs. Patient materials (brochures and online information) were consistently written at levels higher than the recommended sixth grade reading level, and patient recall after informed consent was “pretty atrocious,” according to Dr. Aaronson. The studies that looked at improving patient education showed that adding a visual or interactive component, such as practice drills or a video, improved patient understanding and recall.

Identifying Patients with Low or Limited Health Literacy

Ten percent of patients have inadequate health literacy, with more than 26% showing difficulty filling out medical forms, reading medical material, or understanding written information.

© Production Perig / shutterstock.com

“Otolaryngologists should employ health literacy screening to identify patients who may require additional help navigating the healthcare system,” said Dr. Megwalu, who recently published another rare study that looked at health literacy in otolaryngology (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;155:969–973).

In the cross-sectional study, Dr. Megwalu and his colleague used the Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS), a formal measure of health literacy, to assess 316 adults treated at three of Stanford University’s tertiary adult otolaryngology clinic sites.

Ten percent of patients had inadequate health literacy, with more than 26% showing difficulty in at least one of three health literacy domains (i.e., filling out medical forms, reading medical material, or understanding written information about their medical condition). Socioeconomic factors linked to lower health literacy included less education (high school or lower), racial minority (except for Hispanic), and not having English as a primary language. Age and sex were not found to be linked to health literacy.

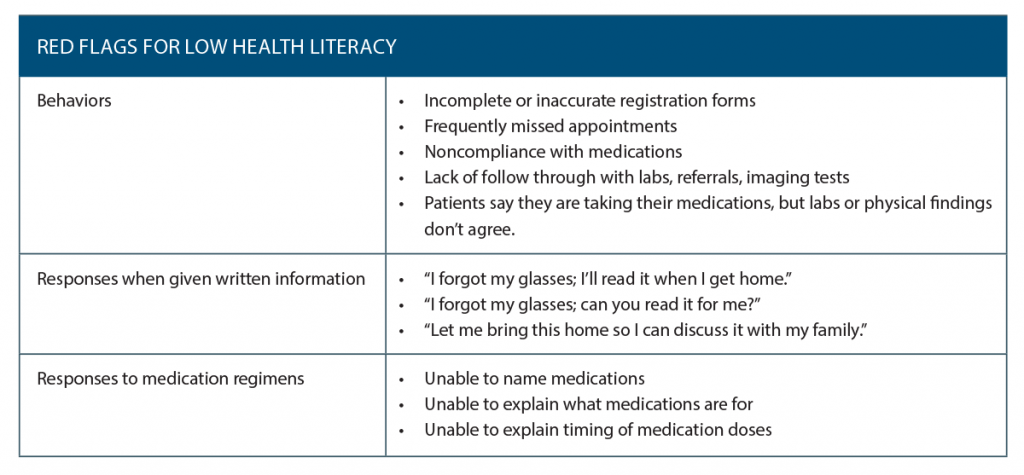

Along with using informal assessment in which physicians employ cues from the patient regarding their level of understanding and adherence to treatment plans (See “Red Flags for Low Health Literacy,” p. 16), Dr. Megwalu stressed the use of more formal tools such as the Brief Health Literacy Screen. Unlike many of the formal health literacy assessment measures, the screen “is easy to apply in clinical practice,” he said.

Health literacy has a substantial impact on treatment outcomes, and data from many of the studies cited above support the need for otolaryngologists to screen patients for health literacy. When physicians are aware of this need, patient outcomes improve.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical writer based in Minnesota.

Brief Health Literacy Screen

- How confident are you about filling out medical forms by yourself?

- How often do you have someone help you read hospital materials?

- How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written material?