© Burger/Phanie / Science Source

According to the National Sleep Foundation, 50 to 70 million Americans are affected by chronic sleep disorders and intermittent sleep problems. In-home sleep studies have become a large part of diagnosis in sleep medicine, and their presence continues to grow—a 2019 report on home sleep apnea testing devices by Global Market Insights reported that the market is set to exceed $1.4 billion by 2025. Although home tests have become more sophisticated, they may not be appropriate for some patients. It’s in the otolaryngologist’s best interest to know which is best for each patient’s needs.

Do all patients with possible sleep apnea need diagnosis in a sleep clinic? Home testing may be more comfortable and budget friendly, but its technology may miss mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and other sleep disorders. When appropriate, home testing enables the diagnosis of more patients, so they can begin continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or another therapy, otolaryngologists say.

“Many patients want a home study, and they may be good candidates for one. It’s a good test and starting point for patients with high suspicion of sleep apnea,” says Pell Ann Wardrop, MD, an otolaryngologist and sleep medicine physician at CHI Saint Joseph Health in Lexington, Ky. Patients on oxygen supplementation or with some comorbidities cannot be diagnosed with home-based tests, so Dr. Wardrop believes that in-lab tests aren’t going away. Her four-bed sleep center, open since 1999, is always busy and hasn’t closed at all during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lab Versus Home

© rumruay / shutterstock.com

Typically, a physician will order a sleep study for a patient whose results on standard, short sleep questionnaires, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale or STOP-BANG test, suggest a higher likelihood that they have OSA or another sleep disorder, said Masayoshi “Mas” Takashima, MD, chair of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Houston Methodist ENT Specialists in Texas.

Sleep clinic patients generally arrive at Dr. Wardrop’s clinic at 8:30 p.m. and take a split-night study: one three-hour test to detect sleep apnea and a second test where they sleep with a CPAP or auto-PAP to adjust the mask fit and oxygen levels, said Dr. Wardrop. The clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing of OSA, published by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) in 2017, recommends the split-night testing protocol for in-lab studies. If an initial laboratory polysomnography is negative, but a clinical suspicion of OSA remains, a second in-lab test is recommended. The sleep center’s staff includes a neurologist, pulmonologist, cardiologist, five full-time and two part-time sleep technicians, two registered nurses, and a certified medical assistant/receptionist.

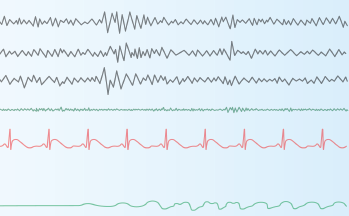

Technicians video the patient during sleep and measure 10 or more sleep parameters: sleep and sleep stages scored by at least three electroencephalogram (EEG) leads, electrocardiogram results, leg movements, respiratory flow, respiratory effort, oxygen levels, carbon dioxide levels, muscle tone, scoring, and eye movement.

At-home sleep tests generally involve a simplified breathing monitor, much like an oxygen mask, that tracks a patient’s breathing (pauses or absences) and breathing effort (whether breathing is shallow) while worn; a finger probe to determine oxygen levels; and a belt worn around the midsection, linked to the monitors. Some models also have sensors for the abdomen and chest to measure rise and fall while breathing. Most at-home sleep tests are used just for one night and returned to a sleep clinic the next day. Sleep technicians then create a detailed report based on the results.

Newer at-home models have made strides in lowering the number of contact points required, with a small monitor worn on the wrist, a pulse meter worn on the finger, and a single sensor on the chest. Some devices use a smartphone app to replace the battery and monitor, automatically transmitting results to a sleep technician through the cloud.

Home Benefits and Drawbacks

Validated, established home tests play an important diagnostic role and offer other benefits, according to Edward M. Weaver, MD, MPH, professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery and chief of sleep surgery at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. “Patients sleep in their own bed. They’re less cumbersome to set up, so patients often sleep more naturally.”

The main limitation of home sleep apnea tests is the lack of a direct sleep measure, or EEG, which impacts some sleep apnea parameters, or underestimates them, said Dr. Weaver. “For example, the apnea-hypopnea index is defined as the number of breathing pauses per hour of sleep, so the duration of sleep is part of the definition. Home sleep apnea tests use proxies for measurement of sleep, such as the recording time or actigraphy [measure of activity]. Some proxies are better than others. In-lab polysomnography directly measures sleep by EEG, so it has an accurate measure of sleep time, providing greater accuracy. In-lab testing is also more reliable because it’s monitored, so if something goes haywire during the test, it gets fixed quickly, whereas a home test may just show a technical failure,” he said.

Most home sleep apnea tests still require direct visual review of the raw data that are collected. There’s some physician review, but the amount of review may vary, because the scoring of these home sleep apnea tests can be automated. —Eric J. Kezirian, MD, MPH

Home sleep tests have obvious benefits for appropriate patients, agreed Eric J. Kezirian, MD, MPH, professor of sleep medicine and vice chair of the Caruso Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. “The general advantages include lower costs, greater convenience, and the possibility of a more natural assessment because there are fewer monitors attached to the body, and the patient is sleeping in their own bed,” he said. “The disadvantages include the fact that there can be displacement of monitoring devices, making the study of inadequate quality and needing to be repeated, and the fact that fewer monitors collect less information.”

The AASM guideline acknowledges that “measurement error is inevitable” in the technology because EEG, electro-oculogram (EOG), and electromyogram (EMG) typically aren’t monitored. It also states that because of cost and lack of proximity to a sleep clinic, home testing may be “less costly and more efficient” for appropriate patients.

Home sleep testing measures limited parameters by comparison: usually oxygen saturation, pulse, respiratory flow, and respiratory effort. Because in-lab polysomnography provides a fuller set of measures for sleep apnea and other sleep issues, such as sleep-stage abnormalities, said Dr. Weaver, patients with complicated sleep apnea should spend the night in a clinic to confirm diagnosis—as should anyone with suspected sleep apnea who receives a negative result from a home test.

Why do some patients with highly suspected OSA get a negative result on their home test? Technical failure, such as unreadable or missing data or incorrectly attached monitors, can happen at home, said Dr. Weaver. Other potential pitfalls of home tests include a mismatch between actual sleep time and proxy sleep time, which may happen if a patient has difficulty falling asleep or cannot stay asleep during the night, and other sleep issues that throw off the results, such as a limb movement disorder.

If a patient’s home test is negative, but they still have suspected sleep apnea due to their symptoms, most insurance policies will cover a follow-up in-lab test. “I don’t think home sleep apnea testing is causing people to be misdiagnosed,” said Dr. Weaver. “It may in fact be increasing access to testing, so more people are getting diagnosed.”

“An at-home sleep study can only tell if a patient has obstructive or central sleep apnea; it’s most effective to diagnose moderate to severe apnea. Mild OSA can result in a false negative result, but typically a sleep lab would be able to pick it up,” said Dr. Takashima. “There are many other sleep disorders that wouldn’t be picked up by a home sleep study, such as narcolepsy or sleepwalking.”

Home sleep tests may underestimate OSA severity and miss other sleep disorders because they cannot detect events that cause patients to awaken without drops in oxygen levels and cannot always detect if a patient is awake for prolonged periods during the night, noted Dr. Kezirian. “Most home sleep apnea tests still require direct visual review of the raw data that are collected. There’s some physician review, but the amount of review may vary, because the scoring of these home sleep apnea tests can be automated,” he said.

[Home studies] are less cumbersome to set up, so patients often sleep more naturally. —Edward M. Weaver, MD, MPH

Costs are certainly lower for home studies—home-based sleep tests may cost as little as one third of the price of an in-lab sleep study, according to estimates from Johns Hopkins Medicine. Yet, there’s concern that cost may drive both patients and insurers to push for home tests.

“In-lab sleep testing is more expensive to the system for sure, as it requires personnel to monitor patients through the night, much more sophisticated equipment, adequate space, and more disposable supplies,” Dr. Weaver said. “The out-of-pocket cost to patients is also higher, because it’s usually a percentage of the charge.”

“For many years now, insurance companies generally wanted almost all patients to get home sleep apnea tests instead of in-laboratory polysomnograms,” said Dr. Kezirian. Despite the strong recommendation by the AASM that only patients with a high likelihood of OSA should be prescribed a home test, “the reality is that insurers want the home studies for many patients, except those with significant cardiac or pulmonary disease or other sleep disorders that can be evaluated only with an in-laboratory sleep study.”

The Right Fit

Which patients are good candidates for home sleep testing? The AASM guideline recommends either laboratory polysomnography or home sleep apnea testing to diagnose uncomplicated adult patients with signs and symptoms that indicate increased risk of moderate to severe OSA. If a patient’s home test produces a negative or inconclusive result, or is technically inadequate, lab-based polysomnography is recommended. The guideline strongly recommends lab over home testing for patients with significant cardiorespiratory disease, potential respiratory muscle weakness due to a neuromuscular condition, awake hypoventilation or suspicion of sleep-related hypoventilation, chronic opioid use, history of stroke, or severe insomnia. In a 2018 statement, the AASM updated its guidance to state that a home testing prescription should be based on the patient’s medical history and a face-to-face or telemedicine visit with a medical provider.

“Even if a patient orders the tests online, they still need to get the results from the company that provided the patients with the machine,” said Dr. Takashima. “Typically, they’ll have a board-certified sleep doctor review the data and provide the results to patients. There are some companies that use automated reports, but the margin for error for automated results is significantly higher.”

The choice you make should be based on diagnosis and treatment goals for each individual patient. “I always advocate for the best treatment that looks at the body as a whole,” said Dr. Takashima. “A disease process can affect other areas of the body, so it’s always best to see a qualified sleep specialist.”

Susan Bernstein is a freelance medical writer based in Georgia.

Is There an App for That?

Patients have more choices than ever before to monitor their sleep quality and other health data without a prescription. Over-the-counter apps and wearable devices can record the intensity or frequency of snoring, blood pressure, breathing, heart rate, and body temperature. Hundreds of consumer wearable oximetry devices or free smartphone apps may record snoring intensity or possible breathing stoppages during sleep that may suggest OSA.

According to the American Sleep Association’s website, smartphones may one day include external sensors to collect more health data from the user’s body, including continuous oximetry readings to detect possible OSA. Currently, phones use heart rate to measure pulse oximetry. Future apps may include more accurate tests that send data to a sleep center or physician.

“Sensors have become widely available. They’re now made with cheaper, more user-friendly technology. They may provide interesting data, such as your heart rate, blood pressure, or oxygen levels, but there’s a lot of variability. I check my smartwatch data from the day before. These devices still need more scientific validation, but many clinical trials are already underway,” said Robson Capasso, MD, chief of sleep surgery and associate professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford, Calif. He believes that apps and devices are part of a trend toward value-based healthcare and make health data more accessible to patients.

But these data only tell part of the story when it comes to sleep.

Some otolaryngologists are concerned that patients may try to self-diagnose OSA with an over-the-counter device or app instead of seeing a clinician for a prescription sleep study. These tools aren’t validated for use as diagnostic tools, said Edward M. Weaver, MD, MPH, professor of medicine in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery and chief of sleep surgery at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. “It’s unclear how well they measure sleep under ideal conditions, let alone under real-life conditions. One other concern with self-diagnosis is that other important health issues may be mistaken for sleep apnea, such as obesity, hypoventilation syndrome, or central sleep apnea. These warrant other testing and/or treatment.”

“Your diet, whether you’ve been drinking that evening, your sleep position, or recent weight loss or weight gain can make the results vary as well,” said Dr. Capasso. “Some patients may think about their sleep quality too much and become excessively concerned. It’s important for patients not to over-catastrophize about their health based only on their smartphone.”