Climate change refers to an observed long-term change in global weather patterns. Due to a population- and economic-driven increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, there has been an increase in average surface temperature of 1℃ since the late 19th century. This increase in global temperatures has led to rising sea levels and an increase in periodic severe weather conditions such as wildfires and floods. In addition, many sources of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, such as cars and trucks that rely on fossil fuels, also contribute to poor air quality by releasing airborne particulate matter.

The health effects of climate change are an increasingly urgent public health crisis that are infrequently recognized within the surgical community. The World Health Organization estimates that without reductions in current GHG emissions, climate change will account for 250,000 deaths per year from 2030 to 2050.

As surgeons within a waste- and energy-intensive healthcare system, our contribution to the climate crisis is tangible. The healthcare sector in the United States was responsible for 8.5% of GHG emissions in 2018, which contributed to the loss of 388,000 disability-adjusted life years. While many other industries have adopted sustainability and carbon neutrality goals, the U.S. healthcare sector continues to have the highest per capita carbon emissions in the world, which increased by 6% from 2010 to 2018 (Health Aff. 2020;39;2071-2079).

The Health Connection

Otolaryngology isn’t immune to the effects of climate change. While it might be challenging to fully appreciate the health impacts of the climate crisis on a day-to-day basis, here are four ways your patients are being affected:

Allergic rhinitis: For many general otolaryngologists, the most commonly encountered climate-sensitive disease—and one of the most impactful in terms of both patient quality of life and economic effects—is allergic rhinitis (AR). The negative effects of AR on both pediatric and adult quality of life are well documented, and the economic burden attributable to AR has been found to be higher than that of asthma, diabetes, and cancer (Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2016;36:235-248). Global warming, increased carbon emissions, and air pollution have been associated with increased aeroallergen production, more geographically diverse pollen, and longer growing seasons (Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2020;12:771-782), all of which may contribute to an increased burden of allergic airway diseases and sinusitis (Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:274-278; Environ Health. 2012;11:25). As temperatures and aeropollutant concentrations continue to rise due to climate change, the economic and psychosocial burden of AR will likely continue to rise as well.

Cutaneous head and neck malignancy: The last 10 years have been the hottest decade on record. The incidence of skin cancer, which is strongly associated with heat and ultraviolet exposure and has a high predilection for sun-exposed areas such as the face, ears, and scalp (Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:35-43), is predicted to drastically increase by 2050 due to anthropogenic depletion of the ozone layer and higher temperatures (Phys Med Biol. 2004;49:R1-11).

Access and quality of care: Climate change affects our ability to provide safe, high-quality care to our patients. Access to surgical services is often disrupted during natural disasters (J Health Serv Res Policy. 2019;24:219-228), which are increasing in severity and frequency. This is exemplified in the U.S., where 2020 broke the record for the number of climate-related disasters, such as flooding, hurricanes, and wildfires. In addition, rates of surgical site infection have been found to be significantly higher during summer months than non-summer months (J Orthop Sci. August 12, 2020. doi:10.1016/j.jos.2020.05.015; Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142(3):653-660), which may be due to proclivity of bacteria for the hot, humid conditions that are becoming more prevalent with global warming.

Sleep-disordered breathing: Air pollution and climate change are inextricably linked. One of the main health consequences of air pollution is the inflammatory impact on the respiratory system. This is a concern for patients, as snoring in children and sleep-disordered breathing in adults have been shown to positively correlate with regional and seasonal variances in air quality (Eur Respir J. 2014;43:824-832; Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:819-825). (To view more research on the impact of climate change on quality of sleep, see “Sleep and Climate Change.”)

Tray reformulation can decrease not only waste, but also cost, by an average of $9,524 per OR annually.

Achieving Carbon Neutrality

Given the well-documented and worsening effects of climate change on public health, it’s imperative that all healthcare providers, including otolaryngologists, take conscious and meaningful steps toward carbon neutrality. Being carbon neutral means that your practice emits the same amount of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that it offsets by other means.

While there are many data-driven sustainability initiatives that, when taken together, can help a healthcare practice come closer to carbon neutrality and yield a net savings of $56,000 per operating room annually (bit.ly/greeningtheor), the following three are most applicable to otolaryngology:

- Redesigning surgical trays to eliminate redundant and/or unused items. Tray reformulation can decrease not only waste, but also cost, by an average of $9,524 per OR annually. One study of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy trays in a pediatric tertiary care hospital found that 12 of the 40 disposable items in the current trays weren’t being utilized, and removal of these items could decrease hospital waste production by 1.48 tons annually (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147:615-618). Given the low infection risk of certain cases such as tonsillectomies, adenoidectomies, direct laryngoscopies, and nasal endoscopies, removal of excess disposable drapes from trays and conversion to field sterility (i.e., mask, sterile gloves, sterile drapes of surgical site only) can be considered. While the safety of field sterility has been established for hand surgery (Hand (N Y). 2011;6:60-63; Hand (N Y). 2019;14:808-813) and Mohs surgery (JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1378-1385), further research is needed to determine the role of field sterility in otolaryngology.

- Reprocessing single-use items or replacing them with reusable alternatives. Given that the majority of otolaryngology cases are clean-contaminated, there are many opportunities for eliminating wasteful single-use devices (SUD) that have limited utility in terms of infection control. For example, single-use plastic tip guards for nasal atomizers can be replaced with Venturi atomizers cleaned with alcohol to minimize cross-contamination (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:411-413). Examples of SUD in OHNS that are eligible for reprocessing include coblation wands, adenoid blades, harmonic scalpels, shavers, and microdissection needles (Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2019;52:173-183). The use of reusable gowns and drapes as opposed to single-use textiles can significantly reduce solid waste production and may be well-suited to clean-contaminated otolaryngology cases without implants given mixed data on infection outcomes (Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72:S165-169; Am J Surg. 1986;152:505-509; J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:960.e961-920).

- Considering total intravenous anesthetic instead of anesthetic gases. Despite being released in small quantities, waste anesthetic gases have a large carbon footprint due to their ability to trap heat over a 100-year period. In practical terms, the carbon emissions from one hour of desflurane use in the OR are equivalent to those resulting from driving a car for 230 miles. As such, the environmental impact of volatile anesthetics is significantly higher than that of intravenous, regional, and neuraxial anesthetics (Anesth Analg. 2012;114:1086-1090). Given that total intravenous anesthetic (TIVA) has been shown to improve surgical field visibility, decrease blood loss, and decrease operative times in endoscopic sinus surgery when compared to inhalational anesthetics (Rhinology. 2019;57:402-410), opting for TIVA when medically appropriate can have both patient care and environmental benefits.

Although some healthcare systems have begun to address their carbon footprint through involvement with organizations such as Practice Greenhealth, a nonprofit membership and networking organization for sustainable healthcare, it’s rare for surgeons to be visibly involved despite our role as leaders within the healthcare field. There are many opportunities for advocacy and research within the field of sustainable healthcare, and otolaryngologists in every stage of training and every type of practice are capable of becoming a driving force for positive change. It’s imperative that we each take a step toward sustainability and carbon neutrality for the health of our patients and our planet.

Dr. Dilger is a surgeon at Massachusetts Eye and Ear and an instructor in otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Tummala is an assistant professor of surgery at the George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. Dr. Krane is an otolaryngologist specializing in facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at The University of Kansas Medical Center.

Healthcare and Greenhouse Gases

“Health Care’s Climate Footprint,” published jointly by Health Care Without Harm, an international nongovernmental organization focusing on sustainability and the worldwide health sector, and Arup, an environmentally focused firm of designers, planners, engineers, architects, consultants, and technical specialists, offers a detailed estimate of healthcare’s global climate footprint. The report contains some startling facts about the impact that worldwide healthcare has on the planet:

- The global healthcare industry is responsible for 2 gigatons of carbon dioxide each year, or 4.4% of worldwide net emissions—the equivalent of 514 coal-fired power plants.

- If the global healthcare sector were a country, it would be the world’s fifth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases on the planet. Healthcare’s climate footprint is smaller than that of China, the United States, India, and Russia, but larger than that of Japan and Brazil.

- The top three emitters of healthcare greenhouse gas emissions, the United States, China, and the collective countries of the European Union, comprise more than half (56%) of the world’s total healthcare climate footprint.

- A limited estimate covering 31 countries showed that an additional nearly 1% of healthcare’s global climate footprint—nearly 4 million metric tons of emissions—come from the sector’s use of anesthetic gases and metered dose inhalers.

- The gases commonly used for anesthesia (nitrous oxide and the fluorinated gases sevoflurane, isoflurane, and desflurane) are potent greenhouse gases. At present, the majority of these gases enter the atmosphere, contributing at least 0.6% of healthcare’s global climate impact.

- When viewed across healthcare facilities, purchased electricity, steam, cooling and heating, and supply chain emissions, more than half of healthcare’s footprint is attributable to energy use—primarily the consumption of electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply combined with health sector operational emissions.

- There’s a strong but not absolute correlation between a country’s healthcare climate footprint and a country’s healthcare spending. Generally, the higher the spending on healthcare, measured as percentage of a country’s gross domestic product, the higher the per capita healthcare emissions come from that country.

There were some data gaps that the report wasn’t able to address given limited time and resources and the nature of the methodology used, but through the recommendations given in the report, the organizations hope to chart the course for zero emissions from healthcare sources by the year 2050. You can read the report in its entirety.

—Amy E. Hamaker

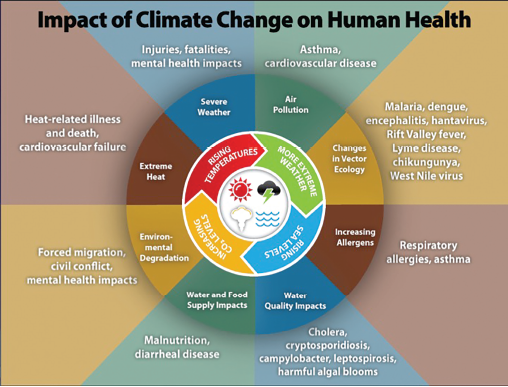

CDC Breakdown on Climate Change Effects

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/effects/default.htm