TRIO Best Practice articles are brief, structured reviews designed to provide the busy clinician with a handy outline and reference for day-to-day clinical decision making. The ENTtoday summaries below include the Background and Best Practice sections of the original article. To view the complete Laryngoscope articles free of charge, visit Laryngoscope.

TRIO Best Practice articles are brief, structured reviews designed to provide the busy clinician with a handy outline and reference for day-to-day clinical decision making. The ENTtoday summaries below include the Background and Best Practice sections of the original article. To view the complete Laryngoscope articles free of charge, visit Laryngoscope.

Explore This Issue

June 2021BACKGROUND

Pediatric tracheotomy is performed over 4,800 times annually (Laryngoscope. 2013;123:3201-3205). A spectrum of postoperative complications occur from 36% to 60% of the time, including hospital-acquired pressure injuries (PIs) (JAMA Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2016;142:241-246). PIs result in damage to the specific skin subsite and underlying connective tissue, and are often associated with a medical device (Adv Skin Wound Care. 2020;33:36-42). Among the adult and pediatric population, PIs incur over $9 billion in expenses to the healthcare system annually (ibid.). A PI affects the peristomal skin in the early postoperative period and arises as a result of frictional forces generated by the tracheotomy tube, direct pressure from the tube, and the suture-and-strap techniques used to secure a tube in place, among many other factors (Pediatrics. 2012;129:e792-e797). There is currently no standardized and comprehensive reporting system among otolaryngologists for complications after pediatric tracheotomy, so the resultant morbidity is likely underreported. An improved understanding of the pathogenesis of PIs and the development of management protocols for pediatric tracheotomies could significantly reduce morbidity in tracheotomized children and decrease healthcare costs.

PIs range from minor skin breakdown to more advanced-stage injury, with a stage 3 PI signifying full thickness skin loss with exposure of subcutaneous adipose tissue and a stage 4 PI denoting the additional exposure of tendon, fascia, muscle, bone, or cartilage. The National Quality Forum, a nonprofit organization that promotes patient safety, designates advanced-stage (3 and 4) PIs as never events or adverse events that should never occur, and has recommended mandatory reporting that has been adopted in various forms by over 26 states and the District of Columbia. As healthcare payers incentivize patient safety, PIs could significantly affect hospital reimbursement.

Although minor skin irritation and early stage (1 and 2) PIs might not be fully preventable due to a multitude of factors, advanced-stage PIs can mostly be avoided with meticulous perioperative care. In this best practice review, we provide recommendations for peristomal wound management to prevent advanced-stage PIs after a pediatric tracheotomy.

BEST PRACTICE

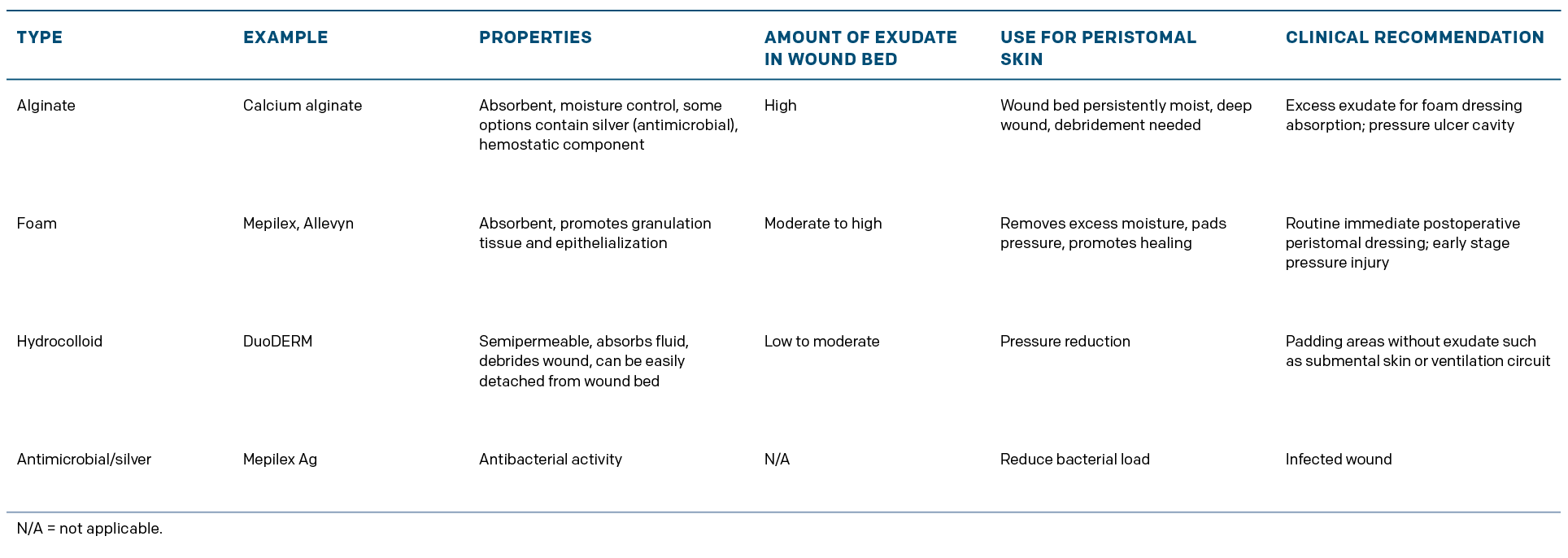

An array of complications may arise after a pediatric tracheotomy, and the clinician should be mindful of advanced-stage PI. Although minor skin breakdown might occur, advanced-stage PIs should rarely develop. We recommend considering placement of an extended tracheotomy tube when individual patient head and neck anatomy permits and when available at the time of surgery. A foam pad should also be placed between the tracheotomy tube flanges and peristomal skin to control the amount of moisture in the wound bed and to redistribute the weight of the tracheotomy tube and ventilatory circuit (Table I). These preventative measures can also be employed in patients with mature stomas if there is concern for skin breakdown. It should be recognized, however, that due to the delicate nature of pediatric skin and other potential factors, including paralysis and immobilization, minor PIs may still occur.