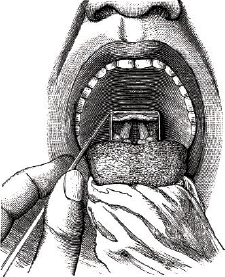

Image Credit: Morphart Creation/shutterstock.com

View of the vocal chords.

A group of experts on vocal fold paralysis tackled an array of patient cases, offering a window into their approaches during a session at the Triological Society 2015 Combined Sections Meeting.

The panel was chaired by James Netterville, MD, director of head and neck oncologic surgery at the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center in Nashville. Dr. Netterville teamed with panelists James Burns, MD, director of quality and safety for the Center for Laryngeal Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital and associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School; Mark Courey, MD, medical director of the University of California San Francisco Voice Center; Gaelyn Garrett, MD, medical director of the Vanderbilt Voice Center; and Marshall Smith, MD, medical director of the Voice Disorders Center at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Here are the cases and the panelists’ responses describing how each might approach care.

Case 1: Accidental Transection

A 33-year-old patient is taken to surgery for a total thyroidectomy, and a nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve is accidentally transected.

Dr. Courey said he would try to perform a primary repair of the nerve if a tension-free anastomosis was possible. Other than that, he said, he might try an ansa transfer. “I don’t know that I’d want to sacrifice the rest of the vagus nerve,” he said.

“If we could get end to end,” Dr. Netterville said, “then this might be a no brainer just to put this back together.”

Case 2: Cancer Affecting the Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve

In this case, a young woman has a total thyroidectomy with bilateral neck exploration with post-operative bilateral vocal cord paralysis. She then has an elective tracheotomy.

At six months, the left fold is functioning again, and the right is still paralyzed. Multiple positive nodes are found; papillary thyroid cancer is invading the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN). The nodes are removed. “There’s no ansa hypoglossi, there’s no ansa cervicalis, so we’re starting to limit our options for primary innervation,” Dr. Netterville said.

Dr. Smith said there were still avenues available. “There are some options with the vagus, with the branch to the thyrohyoid muscle, which drops down off the hypoglossal, which you can jump with an interposition graft,” he said.

The panelists talked about medialization because, if re-innervation is attempted, patients might not see improvement for up to a year. Dr. Burns said that when he first learned medialization, he would go into the operating room (OR) with the skull base surgeon and do a permanent medialization before the tumor was resected, “just in anticipation that those nerves were going to go.” He said he prefers Gore-Tex, but there is flexibility. “Whatever solid material will support the paraglottic space is fine to put in there,” he said.

Dr. Garrett said that in cases where clinically relevant nerve recovery is possible or unpredictable she will use Cymetra (LifeCell, Bridgewater, N.J.) if in the OR and often hyaluronic acid in the office setting as a temporary option.

Case 3: Large Vagal Paraganglioma

In this case, the vagus nerve and ansa hypoglossi are both “gone,” Dr. Netterville said.

Dr. Smith said he would be inclined to sew the ansa cervicalis to the RLN. “Another thing that I look at in this situation is the status of the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve to the CT muscle—it depends on the level of injury to the vagus if the superior laryngeal nerve is also affected, then I will consider doing a double graft with two branches of ansa to both the both the RLN and the SLN [superior laryngeal nerve],” he said.

Case 4: Re-Innervate or Use a Static Procedure?

In this case, a woman is three to six months out after onset of true vocal fold paralysis with no known injury to the RLN. It is thought that she has a good chance of recovery. In these scenarios, common causes are idiopathic, anterior cervical fusion, and thyroidectomy.

Dr. Courey said he would likely image this patient for a neoplasm, even if she’d just undergone surgery. “If this was due to a known cause—the surgery—the use of imaging for ruling out neoplasm is probably not indicated,” he noted, adding that some literature supports that view. “Having said that, I still do it because you want to know. I had a patient the other day who had a known surgery and presented with vocal fold paralysis after the known surgery. And the surgeon got another image—a CT scan—showing a thyroid mass, which was the likely cause. So, even if there’s a known surgery, you could have a red herring.”

Dr. Burns agreed. “I just saw a lady who had 10-year history of having the nerve out that was presumed idiopathic, and I did image her because it wasn’t clear that she’d ever had any imaging, and we found a vagal schwannoma,” he said. He added that he will image again in six months if no cause is found, and in those instances has found thyroid cancer that wasn’t apparent at first.

Panelists tended to agree that they likely would not perform electromyography on this patient. “It’s really not going to impact what I offer as a surgical option,” Dr. Garrett said.

Dr. Netterville said injection laryngoplasty should be strongly considered since the upside is so clear. “It doesn’t seem to have any significant negative or downsides to doing it once or twice to get them out to 12 months,” he said. “You’re now giving the body its opportunity to re-innervate as much as it possibly can.”

“Most of us are probably offering the injection,” Dr. Garrett said. “It’s all about offering. It’s giving options to the patient with proper counseling. I think, overall, we’re probably doing 50-50 in the office versus in the OR.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.