Advanced technology such as virtual surgical planning (VSP) and 3D-printed implants are helping otolaryngologists treat patients with complex facial trauma with more accuracy for improved outcomes.

Explore This Issue

April 2019Oral and maxillofacial surgeons use computer-generated modeling to plan for complex reconstructive procedures and order custom implants from manufacturers for patients who have facial bone loss due to trauma, cancer, or congenital deformities, said Shaun C. Desai, MD, associate residency program director and assistant professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. “We use the 3D technology for more complex cases, such as patients with complex loss of the maxilla or mandible or the skull. For a more complex defect, you can create a shape using the technology, and use it as a guide to make the bone cuts,” said Dr. Desai. “You can be more precise as you take a straight, long bone like the fibula and cut it into the shape of a jawbone. Even now, we often eyeball this technique, and there is asymmetry as a result. It takes a lot of time and surgical expertise. This technology gives you a more precise cut. You basically create a plan for where you will make the cuts into bone before you begin the surgery.”

Scan-Guided Surgery and Custom Implants

First, computed tomography (CT) scans are taken of the damaged facial areas. The surgeon analyzes these images using software designed for virtual surgical planning, said Dr. Desai. The data may also be sent to an engineer at a manufacturer to 3D print customized implants.

“If a patient has a facial fracture, such as a cheekbone that has collapsed, if you don’t fix it quickly, it can heal like that,” said Dr. Desai. The patient may require multiple revision surgeries as a result. To avoid this outcome, “we can use CT scanning to mirror the bad, damaged side of their face to the good side, and repair those maxillofacial injuries.”

VSP is useful for collaboration with an oral surgeon to perform reconstructive surgery on the maxilla, where both specialists use 3D software technology to guide the dental procedure and 3D printing of customized dental implants, said Dr. Desai.

With his patient’s CT scan data on his computer screen, J. David Kriet, MD, director of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City, can examine a malpositioned cheekbone and orbit (such as a zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture) and then measure the patient’s “good side.”

“We can take the right half of the CT in virtual space and flip it over to map out a mirror image. That becomes our plan,” he said. “We can create an orbital implant using the mirrored image. We could either take an implant off the shelf or work with an engineer at a manufacturer to design a custom, patient-specific implant. By doing this, there are a number of advantages. We can do planning and create the implant before we get to the operating room. The time saved often offsets the more expensive implant. The less time we have a patient under anesthesia, the better,” he said.

Dr. Kriet has been using these technologies to plan for many oral and maxillofacial reconstructive surgeries for seven years. While 3D printing and VSP using CT scans are not yet the standard of care, these tools improve accuracy in more complex surgical cases, and they lower the risk of long-term discomfort or deformity for patients, he said.

Improved Outcomes

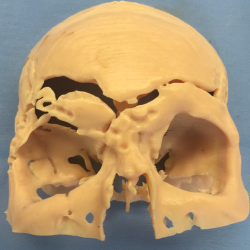

Working model of frontal reconstruction.

Image Courtesy of J. David Kriet, mD

Do these technological advances really improve patient outcomes? In a 2016 retrospective review of 92 patients who underwent osteocutaneous free flap reconstruction of the mandible at a single cancer center from 2002 to 2013, researchers compared outcomes for 43 patients whose surgery was based on prefabricated models to those for 49 patients who had preoperative CT-guided surgical plans (Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:619–623). The authors concluded that VSP refined mandible reconstruction with osteocutaneous free flaps through patient-specific cutting guides, improved reconstruction accuracy, and decreased operating time.

Christopher F. Viozzi, MD, DDS, an oral and maxillofacial surgeon at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., uses these technologies to plan for many different procedures, including surgical reconstruction for patients who have had cancer, benign tumors that destroyed bone and soft tissue, or congenital deformities.

“In my own practice, I use [VSP] to plan for craniofacial surgery, including skeletal and soft tissue deformities. We try to normalize the bone and tissue as much as we can,” said Dr. Viozzi. “We use 3D models for virtual surgical planning all the time and for all sorts of operations, not just post-traumatic surgery. This technology is actually used more often for facial reconstruction than for post-traumatic corrections. To clarify, there are specific patients who come into the clinic with severe facial traumas and acute injuries. We will use computer-generated data to plan for their surgery.”

CT scans are used to help surgeons understand how their patient’s anatomy may vary from that of a normal patient, said Dr. Viozzi. He and his surgical team take precise measurements of the patient’s face or jaw and examine the patient’s unique facial symmetry. “We use this technology to see how an injured side of the face looks compared to the other, uninjured, side to help us plan for the surgery. The data can be used to create a model through 3D printing. There is a use for this in planning for acute, early treatment of a trauma patient as well, and we use the CT data for surgical navigation. We can use this data to pinpoint where certain things are located on or within the bony structures of a patient’s face,” said Dr. Viozzi.

Efficiency and Accuracy

VSP could reduce overall treatment time for patients with facial trauma or deformities because it improves the accuracy and quality of reconstructive surgery, not because it makes the surgery faster, said Dr. Viozzi. “Surgery has nothing to do with speed. We want to be efficient, careful, thoughtful, and accurate. We want to go into surgery with an accurate, well-thought-out plan. We want to do the procedure once, and get the patient to the end of the surgery as close to the surgical plan as we can,” said Dr. Viozzi.

Post-traumatic surgery patients often undergo multiple revision surgeries if the first surgery was performed incorrectly or if other factors prevented prompt treatment, and their bones have healed in incorrect positions, he added. “So, 3D technology can help us virtually plan the surgery, and 3D modeling can help us plan for revision surgery too.”

In a 2017 study of 10 patients who required orthognathic surgery, researchers found that VSP using CT and surface scanning of the upper and lower dental arch to generate 3D models of their skulls, as well as computer-aided design of fabricated surgical splints, improved surgical accuracy and facilitated planning (J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:1962–1970).

To treat a patient with cancer in the mandible, Dr. Viozzi may work with a multidisciplinary team to virtually plan what portions of the jaw need to be removed along with the tumor and how to reconstruct the defect with a portion of the patient’s fibula, and to work with a prosthodontist to pinpoint where dental implants will be placed. “This approach takes a patient from an 18-to-24-month, multistep process to one surgery. It will make that surgery and time in the operating room longer for us, but it makes the surgery process more efficient for the patient,” he said.

Customized implants or plates based on CT scan data can be made in about one to three weeks, said Dr. Desai. Costs seem to be going down, and he believes they reduce operating time and improve aesthetic results. “These implants look more symmetrical. Outcomes, in terms of cosmesis, are improved. This may be subjective, but I get better results from it,” said Dr. Desai. “There is definitely a role for this technology, and people are still learning to use it. They are finding more indications for it.” He predicts that these technologies will become more widely available, cheaper, and available on a quicker turnaround.

Oral and maxillofacial reconstructive surgery can positively impact a patient’s quality of life, because facial defects or asymmetry are visible to others every day, said Dr. Viozzi. “Virtual surgical planning fits in perfectly with the concept of patient-specific and personalized medicine. It’s a perfect example of that, and for providing service to the patient with the lowest overall cost, morbidity, and complication possible.”

Susan Bernstein is a freelance medical writer based in Georgia.

VSP and Custom Implants: Any Cons?

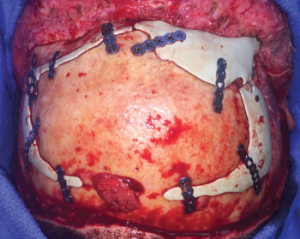

Custom implants secured.

Image courtesy of J. David Kriet, MD

Are there any potential pitfalls for VSP or 3D-printed implant customization that head and neck surgeons should know about? In a retrospective analysis of 54 virtually planned craniofacial surgeries performed from July 2012 to October 2016 at the University of Montreal Teaching Hospitals, researchers analyzed surgical errors. The study included 46 orthognathic surgeries and eight free bone transfers (Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6:e1443).

While 85% of the orthognathic virtual surgical plans were completely adhered to by surgeons, 11% of the VSPs were partially adhered to and 4% of the VSPs were abandoned, they found. Reasons for partially or totally abandoning the plan included poor communication between surgeon and engineer, poor appreciation for condyle placement on preoperative scans, soft-tissue impedance to bony movement, rapid tumor progression, and poor preoperative assessment of anatomy.

The study’s authors concluded that while VSP is a useful tool for craniofacial surgery, improving outcomes and decreasing operative time, surgeons must be aware of potential pitfalls. They called for more surgical training and experience with these technologies.