Telemedicine is being used in the field of otolaryngology in a variety of ways, including real-time telemedicine, which is live, interactive, and can mimic a real-life encounter between a physician and a patient; store-and-forward approaches, in which healthcare providers collect relevant data and imaging and forward it to a consulting physician for review at a later time; and remote monitoring or diagnostics, said Garth F. Essig, Jr., MD, assistant professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at The Ohio State University’s Wexner Medical Center in Columbus.

But Aaron C. Moberly, MD, assistant professor in the division of otology, neurotology, and cranial base surgery at Wexner Medical Center, said that otolaryngology has been slower to adopt telemedicine approaches compared to other fields like radiology, dermatology, and cardiology—for reasons unknown to him. Because of its reliance on more objective sources of information, such as audiograms, diagnostic imaging, and endoscopy, otolaryngology is particularly suitable for the use of telemedicine.

Benefits Abound

Telemedicine offers advantages to both otolaryngologists and their patients. First and foremost, it brings medical care to the patient so that the patient doesn’t have to travel to a medical facility. “The virtual process saves both the physician, and particularly the patient, time,” said Michael Holtel, MD, a staff surgeon at Sharp Rees Stealy Medical Group in San Diego, who cited multiple studies showing that telemedicine delivers the same or a higher level of patient satisfaction and the same quality of care (Telemed J E Health. 2016;22:209–215; Stud Health Technol Inform. 2014;196:101–106; Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2011;44:1359–1374). The studies targeted specific visit types such as postoperative pressure equalization tube checks.

In addition to time, patients can also save money on healthcare when a telemedicine option is available. In a recent study conducted by Dr. Essig’s group, rural patients who participated in the otolaryngology telemedicine program saved close to $200 per encounter (including travels costs and lost wages) (unpublished data). Because many patients required multiple visits, this savings increased throughout the year.

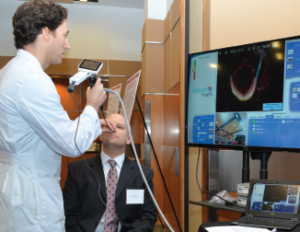

Garth Essig, MD, demonstrates a telemedicine software application to transmit real-time flexible laryngoscopy images to a distant site for telemedicine review by another practitioner.

© Courtesy of The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

Michael A. Keefe, MD, a facial plastic and reconstructive head and neck surgeon at Sharp Rees Stealy Medical Group, said that patients find virtual visits extremely convenient because he can use telemedicine to manage them postoperatively almost entirely, using absorbable suture and Dermabond after skin surgery and for wound care management. “It allows for closer follow-up of postoperative sites and getting the best results,” he said. “The physician can detect an issue with wound healing and the patient can send a photo if they have a concern, allowing for much more rapid and appropriate management, rather than wait[ing] for an appointment to assess the problem—which may advance the issue,” Dr. Keefe said.

P. Daniel Knott, MD, an associate professor of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery and director of facial plastic and aesthetic surgery in the department of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), said otolaryngologists can use remote video examinations to make sure a patient is appropriate for a physician’s expertise. Otherwise, they may have to rely on someone else’s opinion of a patient’s condition.

A study by Dr. Knott and colleagues compared in-person flap assessments with telehealth assessments (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156:1035–1040). “The latter allowed more efficient examination of free tissue reconstructions, while yielding seemingly equivalent information,” he reported. Saving residents’ time was a significant benefit, because UCSF has five hospitals across the city, and excessive work hours means they are often plagued with fatigue.

Telehealth can also bring specialist expertise directly into the primary care setting; otolaryngology is no exception. Primary care providers can, for example, collect videos or images using digital devices—possibly along with other data, like otoacoustic emissions [OAE] test results—which can be reviewed by an offsite specialist, who either provides diagnosis and treatment guidance to the primary care provider or refers the patient to a higher level of care. “When programs like these are employed, one of the most common outcomes is a decrease in wait times at specialty clinics—only the patients who really need the services of a specialist go there for care,” said Linda Branagan, PhD, director of the Telehealth Resource Center at UCSF. “Newborns in rural areas who fail their OAE are a common population target for these types of programs—rural hospitals partner with urban medical centers for access to specialists.”

Drawbacks and Difficulties

Telemedicine does pose some challenges. Being willing to use the technology required for telemedicine can be a significant hurdle. “Both physicians and patients may be reluctant to use it, as this may be a departure from the traditional model where the physician directly examines the patient,” Dr. Essig said. “We need to make sure that the virtual visit is as accurate as a traditional visit.” In a recent study, his group assessed the diagnostic accuracy of evaluating patients remotely and found a high level of diagnostic congruency with a standard visit (unpublished data). Furthermore, both patients and physicians involved in the study expressed a high degree of satisfaction.

Actually using the technology required for virtual medicine, such as obtaining and sending photos, can be difficult for some patients. “Image quality can vary and may require a repeat photo or even a visit if resolution is inadequate,” Dr. Keefe said. “However, today’s smartphone cameras are usually more than sufficient.”

Additional drawbacks include the fact that it can take several hours to get a photo into a patient record for review, and the need for coordination of the physician, patient, and a technological device for live video consultation.

For medical centers, purchasing telemedicine equipment is an expense. “But usually for a limited investment cost and minimal training, you can obtain excellent images,” Dr. Keefe said. Multiple camera adapters allow for the attachment of smartphones to be flexible and rigid endoscopes to examine most head and neck pathology.

Regarding telemedicine’s limitations, Dr. Knott noted that it doesn’t allow for a face-to-face examination, nor can a physician perform procedures such as biopsies or endoscopies. “It limits interaction to simple history acquisition and taking a superficial topical examination, restricting the depth of information that a physician can obtain,” he said.

A major hurdle slowing the widespread use of telemedicine in otolaryngology is the lack of reimbursement from most health insurers. “This significantly limits the applicability of telemedicine for many subspecialty practices, which would otherwise be interested in building telemedicine programs,” Dr. Moberly added.

Where It’s Most Useful

Telemedicine is particularly useful in rural areas. More than 60% of otolaryngologists are located in large cities, where they tend to be over-represented. In contrast, rural areas, and those with relatively low socioeconomic status, tend to have few otolaryngologists. “Clearly, a significant percentage of the United States does not have access to a local otolaryngologist,” Dr. Holtel said (Laryngoscope. 2017;127:95–101).

“Telemedicine solutions can provide better subspecialty healthcare to patients who would not otherwise have access due to geographic and transportation limitations,” Dr. Essig said. “We have the technology and expertise; we just need to coordinate our efforts so that we maintain a high level of care and continue to develop tools that help us bring specialists closer to the patients.”

Tele-access is extremely helpful in patient management in the areas of triage, disposition, and follow-up; it is also ideal for emergency consults, such as photos of tympanic membranes/ears, oral pathology, nasal pathology, skin pathology, and review of pertinent radiologic studies. “Physician extenders (i.e., physician assistants and nurse practitioners) use it to review physical findings while we are in the operating room or at a different location. This expedites care,” said Dr. Keefe, who added that this also decreases the cost of healthcare. Telemedicine can also be used for patient and physician education, because it offers the ability to transmit patient education through a patient portal.

What’s Next?

Dr. Keefe foresees the increased use of common tools in telemedicine, particularly the smartphone, which he believes will play a much more important role in the delivery of real-time medical care in the future. This would include blood pressure and electrocardiogram monitoring, laboratory testing, and other medical tests. “Many groups are already implementing trials of patient smartphones as a care device in the perioperative period to remind the patient about medications as well as postoperative care regimens,” he said.

Virtual intensivist and neurology services in hospitals without access to an on-call specialist are already in use. “One would expect that this would be expanded to non-surgical specialties and simple surgical concerns as well,” Dr. Keefe said.

In addition, “tele-doc companies” for general practice patients who can have evaluations over the phone often obviate the need for these patients to visit a medical clinic for routine medical issues. The “tele-doc” can even call in prescriptions for the patient.

The future of telemedicine in otolaryngology certainly looks bright.

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer based in New Jersey.

Innovations in Otolaryngology Telemedicine

Several vendors now manufacture digital otoscopes and rhinoscopes that can be connected to a telehealth platform to collect and send or store images, said Linda Branagan, PhD, director of the Telehealth Resource Center at the University of California, San Francisco. A few of these devices can attach to an iPhone. Tele-audiology applications allow hearing tests and hearing aid programming to be done at a distance. In fact, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs has a well-established program for this.

Dr. Moberly’s group is focusing on developing software, called Auto-Scope, that will provide automatic diagnostic support for clinicians evaluating ear pathologies. “The goal is to address the societal problem of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of acute otitis media, which is associated with increasing antibiotic resistance, antibiotic-related adverse events, and overtreatment with surgical tympanostomy tube placement,” he added.

The software will use a large database of images and videos that have been collected to provide the clinician with the most likely diagnosis for a new image collected, along with a high level of confidence for that diagnosis and three images from the database that are similar to the image a provider collects.

Thus far, prototype software has been developed that can determine whether a tympanic membrane is normal or abnormal 85% of the time. “Diagnosing ear diseases based on a brief glimpse of the eardrum, or even when using still digital images, is difficult and associated with poor diagnostic accuracy,” Dr. Moberly said. A recent study by his group identified an accuracy rate of only about 75%, even for expert otologists reviewing digital otoscopic images (J Telemed Telecare. Published online ahead of print January 1, 2017). “This suggests the continued need for devices to assist in improving diagnostic accuracy.”