Explore This Issue

November 2024Understanding the data and using evidence to support practices

Fundamental to medical decision making is the challenging task of weighing the benefits against the risks of any given treatment decision. Clinical guidelines and protocols help with this decision making, which is further informed by physician judgment, particularly when the evidence is weak or lacking.

When it comes to the use of surgical post-operative antibiotic prophylaxis, a number of guidelines on its use for prevention of surgical site infections offer recommendations skewing quite clearly toward minimizing use to avoid both adverse effects in individual patients as well as on public health with the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria worldwide. (National Library of Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536429/)

In practice, recommendations to minimize surgical antibiotic prophylaxis are not often adhered to. Part of this may be due to long-standing protocols that don’t match the current evidence, and part may be due to issues such as patient expectations or a physician/health system erring on the side of caution to avoid any possibility of complicated and costly infections.

Maybe we should have a slightly different classification in head and neck cases because we can’t use the same logic for these cases as you can for other parts of the body, such as the abdominal or extremity surgery, where the infection risks may be higher.” — Priyesh Patel, MD

In otolaryngology, specific guidelines don’t exist to inform best practices on the use of prophylactic antibiotics for the many common surgical procedures performed. A 2011 clinical practice guideline on tonsillectomy in children recommended strongly against the routine prescription of peri-operative antibiotics in this setting (AAO-HNS. https://aao-hnsfjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1177/0194599810389949). Until somewhat recently, no other specific guidance has been available for otolaryngologists, but more is needed. In a survey by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) Infectious Disease Committee, members reported routinely prescribing pre- or post-operative antibiotics for 12 of the 17 most common procedures despite the lack of good evidence to support such use. (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:63-66.)

In 2018, Patel and colleagues filled this gap by conducting and publishing a systematic review and meta-analysis of the most current data on antibiotic prophylaxis in tonsillectomy, septoplasty/rhinoplasty, endoscopic sinus, otology, skull base, and head and neck surgeries. To date, it is the most comprehensive assessment of the evidence in otolaryngology.

Best Evidence to Date

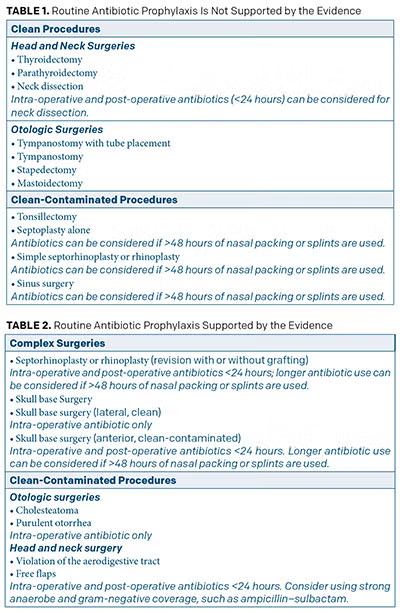

In a nutshell, the review showed that the use of routine peri-operative antibiotics for most otolaryngologic procedures is not supported by the evidence (Table 1) (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158:783-800). These include clean surgeries, as well as those considered clean-contaminated.

In a nutshell, the review showed that the use of routine peri-operative antibiotics for most otolaryngologic procedures is not supported by the evidence (Table 1) (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158:783-800). These include clean surgeries, as well as those considered clean-contaminated.

For surgeries for which the evidence does support prophylactic antibiotics, 24-48 hours post-operatively provides equal benefits to longer use (Table 2).

Priyesh Patel, MD, assistant professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and lead author of the study, said the findings show that even in most of the common surgical procedures performed in otolaryngology that are considered “clean-contaminated” because they require entry through the aerodigestive tract, the risk of infection is low. “I don’t know if people realize the low infection rate,” he said, citing the example of a less than 1% infection rate in sinus surgeries or septoplasty without the use of post-operative antibiotics.

He underscored the fact that for some procedures where the infection rate is still low, notably cochlear implantation, prophylactic antibiotic use is still recommended given the potentially disastrous outcomes if an infection occurs.

Dr. Patel said the decision not to use post-operative antibiotics prophylactically is often most appropriate in patients who are young and healthy and lack any complicating factors that may set them up for poor wound healing or infection. For patients at higher risk of infection, such as smokers or those with immune deficiency or diabetes, prophylactic antibiotics may be indicated even if infection rates are generally low.

Dr. Patel noted that even though most otolaryngologists use “clean-contaminated” to classify surgeries violating the aerodigestive track, he questions the real implications of the classification scheme on outcomes and infection rates. “Maybe we should have a slightly different classification in head and neck cases, because we can’t use the same logic for these cases as you can for other parts of the body, such as the abdominal or extremity surgery, where the infection risks may be higher,” he said, suggesting that a more apt classification of infection risk may help reduce the use of prophylactic antibiotics in head and neck surgery.

Other Otolaryngologists Weigh In

Philip Chen, MD, clinical professor and vice chair in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery/rhinology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, said he thinks post-operative prophylactic antibiotics are overused in otolaryngology. “No one likes complications of surgery, and in an effort to try to minimize infection, many use antibiotics,” he said.

In the past, many patients would not feel they were adequately treated if they didn’t leave the office with some prescription, often an antibiotic. Now I am seeing more patients who are relieved I’m holding off on an antibiotic.” — Philip Chen, MD