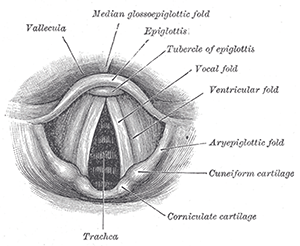

Larynx.

© Bartleby.com: Gray’s Anatomy, Plate 1204

Treating vocal fold paralysis with medialization involves a series of decisions that can sometimes be difficult to make. A panel of experts assembled at the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation Annual Meeting to give tips to session attendees on the best approaches to surgical timing and technique, and to explain how to determine whether medialization is needed at all.

Pre-Procedure Decisions

David Francis, MD, MS, assistant professor of otolaryngology at the Vanderbilt Voice Center in Nashville, said there is often a several-month delay before someone with unilateral vocal fold paralysis actually sees a voice specialist. If a patient sees a general otolaryngologist before seeing the voice physician, it takes a median of nine months to be seen by the voice specialist. “This has significant implications for treatment planning,” he said.

The decision of whether and when to perform an injection augmentation or type I laryngoplasty requires an understanding of the physiology, along with audio-perceptual, visual-perceptual and, importantly, patient-reported factors.

When a patient comes in with vocal fold paralysis, physicians should immediately start thinking about the long-term approach. “We should be thinking about how we’re going to work up these patients and how to manage and measure outcomes systematically,” Dr. Francis said.

The question of whether imaging is needed is a matter of some controversy, he added, although there’s been a “long history” of obtaining a computerized tomography (CT) scan to assess the recurrent laryngeal nerve. “A consensus still exists that some imaging should be done to rule out mass lesions along the recurrent laryngeal nerve in most cases,” he said.

Timing from symptom onset to presentation is a key consideration when determining management. Dr. Francis said that it can take six to 12 months for the nerve to regenerate back to the laryngeal muscles it innervates after denervation injury. Determining whether and when recovery will occur is complicated; often, it is not known where the nerve is injured, how severely it is injured, and what the odds of recovery are.

He also noted that “recovery” doesn’t necessarily mean a return to normal vocal fold mobility; it is more important that symptoms improve significantly enough that a patient no longer feels that the surgery is necessary. Some patients do not experience a voice change that is severe or important enough for them to want surgery. “Even when surgeons may perceive the voice as being disordered, we must be careful not to project our biases and conceptions on these patients,” he said. Decisions about management of this condition should be patient centered and not physician centered.

Injection Laryngoplasty

Andrew McWhorter, MD, director of the Louisiana State University Voice Center in Baton Rouge, said that there is a general belief that the earlier an injection augmentation is done, the better the result. But, he said, this may not be true. Published data suggest that injection diminishes the percentage of patients eventually needing framework surgery, but it is debatable whether the timing factors into this outcome.

There is no such thing as a “best” injectable material, he said. “The reason there are so many out there is because none of them have all the best characteristics.” Otolaryngologists should use the material they find to be most reliable in their hands. The goal of the given case also matters—in some, a temporary injectable is preferred; in others, a long-term result is the goal.

The setting for the injection, whether it is the office or the operating room, depends on the comfort and experience of the surgeon, patient anatomy, and tolerance of laryngoscopy, Dr. Francis said. When choosing an injection technique—transoral, transthyrohyoid, transcricothyroid, or transthyroid cartilage—patient anatomy and surgeon preference are major considerations. “The true vocal fold is not in the same position in every single patient by any means at all,” Dr. McWhorter said. There is variability in the level of the vocal fold relative to the top and bottom of the thyroid cartilage, which affects access, he added.

The advantages to performing the procedure in the operating room rather than in the office are that it is simpler to add more material if needed and that the surgeon has more control, which generally leads to more precision, Dr. McWhorter said. He also noted that the published literature suggests that outcomes and risks in intra-office when compared with intra-operative injections do not differ significantly.

Type 1 Thyroplasty

Adam Rubin, MD, director of the Lakeshore Professional Voice Center in St. Clair Shores, Mich., waits nearly a year after the onset of vocal fold paralysis to see how a patient progresses before performing type 1 thyroplasty. “It’s so easy to perform injection laryngoplasty and temporize people and help patients’ symptoms, so why not give a paralyzed vocal fold the best chance to regain mobility or for synkinesis?” he said.

The recipe for a good result is a combination of good anesthesia, a good patient (one who shows commitment to pre- and postoperative voice therapy, is well-informed, and can tolerate being awake for parts of the procedure), a good technique, and a good ear to assess the procedure’s effect.

Anesthesia, he said, should be chosen according to what the anesthesiologist is comfortable with, as long as the patient is just sleepy enough that she can be roused to use her voice at the necessary moments.

Dr. Rubin noted that Gore-Tex tends to make for a quicker procedure, is easier to add and withdraw, and doesn’t require carving an implant, but it can be easy to get some of the ribbon too high or too low. Silastic, he said, tends to be better for larger gaps.

He said it’s a good idea to try to move expediently to “beat edema,” because once that happens it can affect sound quality and may even lead to underestimating the implant size. He added that, although visualizing the glottis is important during the procedure, it’s a big help to have a “good ear.” Sometimes the folds don’t close, but the sound is good. In other cases, the reverse is true. “You want to be able to tell what sounds best as you fashion your implant—improvement can be subtle,” he said.

Arytenoid Adduction

Sometimes the Type 1 thyroplasty isn’t enough, and a patient might be a candidate for arytenoid adduction, said Adam Klein, MD, director of Atlanta’s Emory Voice Center. The Type 1 thyroplasty adjusts the horizontal position of the vocal fold, but an arytenoid adduction—by rotating the vocal fold cartilage back into place—adjusts the vertical position as well.

A consensus still exists that some imaging should be done to rule out mass lesions along the recurrent laryngeal nerve in most cases of vocal fold paralysis. — David Francis, MD, MS

A large glottal gap is often a good indicator that this procedure could be helpful. “When you see the arytenoid is way out laterally, those are the patients we look at and say, ‘This patient has a higher likelihood of requiring an arytenoid procedure.’”

But these are not always easy procedures, Dr. Klein advised. Patients need to be able tolerate the sedation, and previous surgery or radiation to the neck may make the patient unsuitable for an arytenoid repositioning procedure. The vocal demands of the patient may also factor into the decision.

During the surgery, sedation should be such that the patient is awake to use his voice, and he should be allowed to moisten his throat. Dr. Klein warned that muscle tension dysphonia and post-intubation phonation problems could arise during surgery. He also cautioned that the procedure is just a “static geometric solution for a dynamic problem” and that patients should go in with reasonable expectations. Dr. Klein advises patients that he will get their voices as near normal as possible, but that they might still notice some limits.

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Take-Home points

- When a patient comes in with vocal fold paralysis, physicians should immediately start thinking about the long-term approach.

- Published data suggest that injection diminishes the percentage of patients eventually needing framework surgery, but it is debatable whether the timing factors into this outcome.

- The recipe for a good result after thyroplasty is a combination of good anesthesia, a good patient, a good technique, and a good ear to assess the procedure’s effect.

- Sometimes the Type 1 thyroplasty isn’t enough and a patient might be a candidate for arytenoid adduction.