I stated in the last article that our workforce system lacked transparency and was unaccountable, but what does that really mean?

Explore This Issue

June 2022First, imagine a system that has accountability—one in which actual, or credible, projected workforce supply data allow for dynamic adaptation in the training construct. This system would demand some sort of feedback mechanism, but, perhaps more importantly (given what appears to be happening with our supply), a negative feedback loop to decrease training output, either more broadly or at the fellowship level.

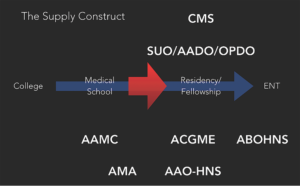

As it turns out, in our otolaryngologist supply chain, no organizational negative feedback mechanism exists to apply supply controls (see Figure 1 to take a look at our supply construct and the organizations that surround it):

- The American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) and American Medical Association (AMA) are set up to look at broader trends, their specialty data may be faulty (see the urology analysis in the Part I article in the May 2022 issue), and they have no control over otolaryngology positions—if anything, they push for more supply earlier on in the training pathway.

- The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) explicitly states that it does not take workforce numbers into consideration when approving new programs or spots.

- The American Board of Otolaryngology– Head and Neck Surgery (ABO-HNS) focuses on individual competence, not the workforce.

- Our academic administrator organizations (Association of AcademicDepartments of Otolaryngology (AADO), Otolaryngology Program Directors Organization (OPDO)) concentrate on education.

- The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) is best positioned to look at these issues, but it lacks control over the spigot.

Think about how lucky we are that we have excess demand for our specialty—we can turn the spigot on or off as we choose, at least in theory. But no organization has oversight to exert that control. And so, given this construct, excess demand for our specialty has the potential to become a liability. Incentives don’t exist for reducing supply at the training program level. In fact, there are incentives for the exact opposite: to grow, even while academicians simultaneously recognize that we have too much supply, as shown in the previous article. You can’t blame them—they see demand and move to meet it.

We should have a comprehensive understanding of what it means to be a practicing otolaryngologist, at a minimum assessing general and subspecialty skillset use by age and geography. Taking ownership of our data benefits our patients and our specialty —Andrew J. Tompkins, MD, MBA

Revisiting our emergency medicine (EM) example, there seems to be a basic recognition now, given the market forces and supply/demand analysis examined in the EM workforce paper (Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78:726-737), that we’ll have a significant excess supply of EM physicians by the end of this decade. And while some might advocate for an increase in residency training time from three to four years, this only affects one graduating class one time, and only for the programs not already at four years.

The other challenge is actually getting this accomplished in a respectable time period given competing incentives. EM doesn’t have much time before significant supply excesses are predicted. And, in the face of these challenges, if new training programs wanted to launch and could justify their existence based on training numbers, the ACGME would ignore workforce realities and bless their emergence, further worsening the supply situation. This construct isn’t a system built for dynamic control or accountability.

So, if our internal responses will be sluggish, taking years to adapt if at all, and if we face a lack of explicit control over the training construct, an accountable system is primarily reliant on one thing: job market transparency.

An accountable system would require participants in the training supply pathway to make dynamic and efficient decisions in response to these transparent changes. Based on the supply concerns we previously discussed, more broadly and in multiple subspecialties, those in the training pathway don’t appear to be receiving transparent information or reacting as one would expect.

Part of the problem, aside from underlying incentives, is that most specialties, including otolaryngology, rely on sporadic workforce publications to create transparent workforce information. The problem with this is that if the publication isn’t timely, as may be the case in EM, we don’t have time to adapt. On the other hand, a single paper may have inaccurate data, making its projections and conclusions misleading, or the conclusions could be spot on but for a specific time period only. This sporadic information outflow can allow for narratives, and decisions based on those narratives, to persist for years, until perhaps a new paper emerges. This process isn’t efficient or dynamic.

We need regular, transparent workforce data. In my opinion, the organization best suited to address this need is the AAO-HNS, based on its stature, influence, and underlying charge to best serve the interest of our patients and members. Routine analyses should be undertaken and published so that medical students, residents, fellows, and even practicing otolaryngologists can make more efficient decisions. We should have a comprehensive understanding of what it means to be a practicing otolaryngologist, at a minimum assessing general and subspecialty skillset use by age and geography. Taking ownership of our data benefits our patients and our specialty.

Meaningful Supply Metrics

But even if we study our specialty’s workforce routinely, what constitutes an adequate supply? For decades, we’ve used the number of otolaryngologists per 100,000 population as the basis for determining an adequate workforce supply. Every specialty and organization uses this number.

Following the same methodology others have used through exact training number projections, I produced a workforce supply projection of 3.61 otolaryngologists per 100,000 population for the year 2025. This would seem to point to an oversupply—a shocking one at that, given previous demand estimates. In the last article, I showed how this supply metric has increased significantly over time. I also highlighted the significant advanced practice provider (APP) growth that further increases our productivity. But something is missed in all of this.

This supply metric of 3.61 simply represents a number of people serving another number of people. The truth is that supply and demand are more complex. Supply input factors such as age, demographics, generational attitudinal shifts toward work, the scope of our specialty, competition, the scope of one’s practice and specialty training, technology, electronic health records, burnout, reimbursement, APPs, and willingness to travel all affect one’s ability and willingness to supply work. Because all of these supply inputs constantly change over time, we can’t even meaningfully compare the number of otolaryngologists per 100,000 metric over time, as we’ve been doing for decades. It’s like comparing apples and oranges.

Further to that point, demand inputs, which affect the denominator of the traditional supply metric, are always changing. Do we think workforce demand hasn’t changed with the Affordable Care Act, high deductible health plans (HDHPs), the general cost of care, and COVID-19, or that demand is the same in all geographic locations? Even if we hold all supply inputs constant over time, if demand is shifting under our feet or differs across regions, the same number of otolaryngologists per 100,000 population won’t necessarily reflect our ability to meet patient demand over time. I believe this traditional supply metric should be abandoned as a descriptor of meaningful information.

We need something that involves a measure of patients’ access to our services, as the 3.61 metric tries to do, but is comparable over time. What’s the one thing we can measure where all these supply and demand factors coalesce, so we don’t have to measure and model them out individually? It all boils down to wait time.

After all, to say that we’ll have a supply shortage is to say that wait times will be longer; with a workforce oversupply, wait times will be shorter. If APPs increase our productivity, we’ll have shorter wait times. More burnout? More time. Technological disruption? Less time. Generational shifts toward more work–life balance? More time. Increasing costs and HDHPs? Less time.

We can also judge wait time across time periods: A two-week wait now is the same as a two-week wait 10 years from now. We can define time from the perspective of quality by more specific metrics of new patient availability or surgical wait times. We can assess time differences across regions and by practice type, thereby showing where job needs exist. Wait time allows for a clearer understanding of oversupply or undersupply. It means something on ground level; supply and demand metrics of 3.61 and 3.11 do not.

Wait time, however, speaks to only one quality of a workforce: access. Skillset use points to a different quality, that of bringing optimal care to the patient. If we’re training too many fellows, we’ll see this play out by declining skillset use by indicator cases over time. The ultimate prize for society would be transparent, uniform outcome data, with appropriate controls. Nothing, in my opinion, would inspire more quality improvement projects than that. But despite being armed with better metrics, we still need to think about how to bring these analyses together and also how to craft a more dynamic future workforce. And aside from my training and fellowship growth concerns, we should discuss another uncomfortable factor that molds our workforce in serious ways: competition.

Dr. Tompkins is a private practice otolaryngologist in Columbus, Ohio.