Revisiting our emergency medicine (EM) example, there seems to be a basic recognition now, given the market forces and supply/demand analysis examined in the EM workforce paper (Ann Emerg Med. 2021;78:726-737), that we’ll have a significant excess supply of EM physicians by the end of this decade. And while some might advocate for an increase in residency training time from three to four years, this only affects one graduating class one time, and only for the programs not already at four years.

Explore This Issue

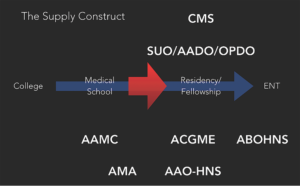

June 2022The other challenge is actually getting this accomplished in a respectable time period given competing incentives. EM doesn’t have much time before significant supply excesses are predicted. And, in the face of these challenges, if new training programs wanted to launch and could justify their existence based on training numbers, the ACGME would ignore workforce realities and bless their emergence, further worsening the supply situation. This construct isn’t a system built for dynamic control or accountability.

So, if our internal responses will be sluggish, taking years to adapt if at all, and if we face a lack of explicit control over the training construct, an accountable system is primarily reliant on one thing: job market transparency.

An accountable system would require participants in the training supply pathway to make dynamic and efficient decisions in response to these transparent changes. Based on the supply concerns we previously discussed, more broadly and in multiple subspecialties, those in the training pathway don’t appear to be receiving transparent information or reacting as one would expect.

Part of the problem, aside from underlying incentives, is that most specialties, including otolaryngology, rely on sporadic workforce publications to create transparent workforce information. The problem with this is that if the publication isn’t timely, as may be the case in EM, we don’t have time to adapt. On the other hand, a single paper may have inaccurate data, making its projections and conclusions misleading, or the conclusions could be spot on but for a specific time period only. This sporadic information outflow can allow for narratives, and decisions based on those narratives, to persist for years, until perhaps a new paper emerges. This process isn’t efficient or dynamic.

We need regular, transparent workforce data. In my opinion, the organization best suited to address this need is the AAO-HNS, based on its stature, influence, and underlying charge to best serve the interest of our patients and members. Routine analyses should be undertaken and published so that medical students, residents, fellows, and even practicing otolaryngologists can make more efficient decisions. We should have a comprehensive understanding of what it means to be a practicing otolaryngologist, at a minimum assessing general and subspecialty skillset use by age and geography. Taking ownership of our data benefits our patients and our specialty.