Treatment of oropharyngeal cancers, which has seen major changes over the years, may be on the brink of yet another development. The newest treatment option on the block is tumor removal using state-of-the-art robotic technology. Several factors have played into the trend, one of which is the availability of the daVinci robotic surgical system (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, Calif.) at hospitals, because the technology has become useful to other departments, such as urology and thoracic surgery. Equally important, though, is the changing nature of oropharyngeal cancers.

The Rise of HPV

Oropharyngeal cancers caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infections are on the rise. A 2011 study analyzed tumors collected by three cancer registry sites for traces of HPV infection and then projected those findings onto the U.S. population. Their results found an incidence rate of 0.8 HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers per 100,000 in 1984. By 2004, that rate had more than tripled to 2.6 per 100,000 (J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294-4301).

If this trend continues, the number of new HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers will surpass the numbers for cervical cancer by the year 2020. Yet, public awareness of tonsil and tongue cancers has not kept pace. News stories about vaccination against HPV still focus heavily on the prevention of cervical cancers in women. If and when vaccination is widely adopted in boys and girls in the U.S, we might expect to blunt the rise in cases—at least a couple of decades from now.

Why HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers are on the rise is not entirely clear, though increased exposure undoubtedly plays a part. The virus is transmitted via physical contact, and sexual transmission is thought to be the primary mode of exposure. The viral strain in tonsil and tongue cancers is the same as in cervical cancer, HPV-16. And, as is the case with cervical disease, a vast majority of people exposed to HPV manage to clear the virus from their bodies. For a small minority, the virus is incorporated into DNA, which leads to squamous carcinoma.

Meanwhile, HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancers have declined by 50% (from two per 100,000 to one per 100,000) over the same time period. Head and neck surgeons have noticed the rise in HPV-associated cancers, and many say that these cases dominate their practices.

While HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal tumors are both squamous carcinomas, there are important differences that can influence choice of treatment. “HPV-related cancers are characteristically smaller primary tumors,” said Robert Ferris, MD, PhD, chief of head and neck surgery at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. “They’re easier to get at and are more resectable, and they also have a dramatically better prognosis, so the morbidity of therapy is much more important to consider.”

In addition, the demographics of HPV-positive cancers are different. “The patients are younger and healthier. They’re not smokers or heavy drinkers,” said Jeremy Richmon, MD, director of the head and neck surgery robotic program and assistant professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “They tend to do much better; their tumors respond better to treatment of any kind.”

Benefits of TORS

Open surgeries were the standard of care in the 1980s, said Dr. Ferris. Then, in the 1990s, chemotherapy and radiation began to replace surgical resection, and the combination remains the standard today. In the early 2000s, a team of researchers at the University of Pennsylvania developed a method for using the daVinci robot to access tumors through the mouth. The key was using a mouth retractor so that surgeons could get three arms into the open mouth, said Gregory Weinstein, MD, co-

director of The Center for Head and Neck Cancer at the University of Pennsylvania. One arm held the camera, and the other two worked as surgeons’ hands. Together with Bert O’Malley, Dr. Weinstein developed a research program, invited surgeons to train with their method, and generated enough data to submit the procedure to the FDA. Approval came in 2009.

Now, with oropharyngeal cancers presenting more often in younger patients with smaller primary tumors and the advent of minimally invasive transoral robotic surgery (TORS), the field has an opportunity to revisit treatment options. “These two things have dovetailed,” said Eric Moore, MD, professor of otolaryngology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He points out that chemotherapy and radiation became favored over surgery and radiation for all the reasons discussed: difficult surgery, serious morbidity, long hospital stays, and long-term consequences. But now, he said, “TORS allows us to revisit this choice.”

A recent study, co-authored by Dr. Richmon, provided early data that if surgery is indicated, patients undergoing TORS have shorter hospital stays than those undergoing traditional open surgical procedures. In this nationwide inpatient study comparing TORS to open surgery, researchers looked retrospectively at more than 9,000 surgical operations for oropharyngeal cancer performed from 2008 to 2009, when the TORS procedure was still very new. A scant 116 of these cases used TORS, and yet none of those patients required either a tracheotomy or a gastrostomy tube. Total hospital costs were more than $4,000 less for TORS than non-TORS procedures (Laryngoscope. 2014;124:164-171).

TORS greatly improves immediate recovery time when compared with traditional open surgery, which frequently requires surgeons to perform a mandibulotomy to access the tumor site. Robotic surgery also prevents some serious long-term quality of life issues. “After chemoradiation,” Dr. Richmon said, “there’s scarring and fibrosis, and patients can experience difficulty swallowing for months and years. TORS allows us to remove the cancer through a minimally invasive approach that translates to very favorable functional outcomes.”

Chemoradiation comes with its own slate of side effects, including mucositis, fibrosis, dysphagia, xerostomia, and tissue necrosis.

Two National Cancer Institute (NCI)-sponsored cooperative working groups are planning prospective clinical trials. Dr. Ferris, who serves on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology working group (ECOG), says that comparing surgical and medical treatments of a class of cancers is an opportunity that shouldn’t be missed. In order to permit direct comparisons of treatments, ECOG trial arms will evaluate deintensification or lowering of radiation doses after transoral surgery. In addition, the treatments will be tested in patients with HPV-positive and HPV-negative oropharyngeal tumors. The transoral surgery can be accomplished with either the daVinci robot or laser microsurgery. In addition to functional outcomes, study objectives will include assessments of feasibility, toxicity, and cost.

Interestingly, the oncologic outcomes of different treatment modalities are not well characterized, said Dr. Richmon. If you compare the survival rates of open surgery, TORS, and chemoradiation, he said, “there’s no high-level evidence supporting one treatment over another at this point. But from a functional standpoint, patients treated with TORS do much better.” And with a younger demographic of patients, long-term side effects have more impact because there are more years of life to interfere with.

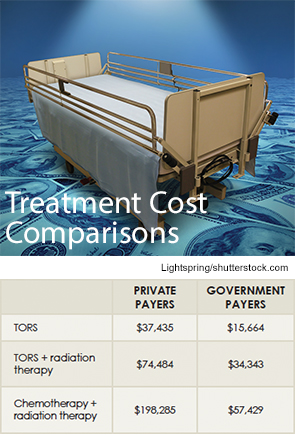

As for cost, TORS is competitive for now. “The machine costs $2 million, but if a hospital utilizes between departments—including urology, otolaryngology, thoracic surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and gynecology—then you spread that cost out,” said Dr. Moore.

Dr. Moore conducted a cost study comparing transoral surgery and standard of care chemotherapy and radiation and found significant cost savings with the surgery (see “Treatment Cost Comparisons,” above).

How the Robot Works

The robot gives the surgeon both an excellent view and articulated robot arm access to those areas just out of sight. Dr. Moore spent a week training at the robot’s manufacturer and then returned to Mayo and started a protocol. Indeed, 50 of his patients underwent the procedure in an off-label use protocol, and those data were combined with that of patients from the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the University of Pennsylvania to submit to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for approval.

The robot’s camera offers a three-dimensional view, said Jeffrey Wolf, MD, associate professor of otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore, “as if you’re standing on the base of the tongue.”

While the visualization is great, practitioners say it can take some effort to understand the new perspective. “You need to relearn the anatomy from the inside out instead of the outside in,” Dr. Moore said.

Dr. Wolf and his partner Duane Sewell, MD, originally trained themselves on cadavers to become certified. Other head and neck surgeons travel to established training programs, such as the one at the University of Pennsylvania, which includes animal and cadaver practice as well as case observation.

For the NCI cooperative trials, study designers had to make sure a certain level of training was in place so that surgeons weren’t “learning on the trial,” Dr. Ferris said. Credentialing includes assessments of negative margins, bleeding, and surgical complications. It definitely takes time to learn and, as with any surgical procedure, some people pick it up faster than most. “Some take 10 to 15 cases to get really good,” he added. “Others may need more than 30.”

Although TORS shines compared with traditional open surgery, it still has some limitations. It’s difficult to extend the resection beyond the base of the tongue, said Dr. Moore. It depends on an individual’s anatomy, but generally the epiglottis, larynx, esophagus, and hypopharynx are out of reach. Tumors in these tissues might be accessible with laser microsurgery; otherwise, they remain candidates for chemotherapy and radiation.

The robot doesn’t have any haptic feedback, or “feel,” Dr. Wolf said. With many tumors, a surgeon will touch the tissue and can tell where a tumor is and where it’s not.

For now, the daVinci robot is the only one commercially available, but there are other companies working on their own versions. They are working to fill those gaps by including haptic feedback and by using smaller arms that can access more remote tumor sites.

Indications for TORS

Transoral surgery may be considered for patients with smaller T1 and T2 stage tumors in the oropharynx and is generally not favorable for larger T3 or T4 tumors, which may result in more destruction of normal tissue.

At the University of Pennsylvania, the procedure is a huge success. “We have a 96% cure rate when TORS is used for HPV-related cancers,” said Dr. Weinstein. “Negative margin surgery works.”

Different hospitals have different guidelines, and indeed, it’s hard to craft clear guidelines, said Dr. Richmon. “It requires an individualized approach to each patient.” At Hopkins, cases are evaluated by a team of physicians, including a surgeon, a radiation oncologist, a medical oncologist, and a speech therapist.

At Maryland, Dr. Wolf’s group is conservative when it comes to choosing surgery. “We offer robot surgery if we think they’re not going to need radiation or chemotherapy,” he said. “Like anything else, it’s just a tool that we use. There’s still a large role for chemoradiation and for conventional surgery.”

Jill Adams is a freelance medical writer based in Delmar, N.Y.

Leave a Reply