One of the uncomfortable truths of medicine is that we compete against one another. We have a shared history, having gone through the crucible of training together—in some cases even in the same program, at the same time. Many of us are friends. Some of the things that attracted me to our specialty and that I continue to be enamored by are the intellect and kindness of our members.

But we must also grapple with the fact that as high-minded, compassionate, and friendly as we are, we still compete with one another. And our organizations’ growth aspirations and our shared marketplace’s competitive dynamics have real implications for the complexion of our workforce.

Transparent outcome data, with appropriate controls, that patients care about should replace the current quality mandates put out by CMS. These transparency changes allow for more efficient allocation of capital—patients will choose to go where they perceive the value is, and workforce changes will follow. —Andrew J. Tompkins, MD, MBA

One of the most basic structural elements of our workforce is our practice environment (hospital, private practice, academic center, etc.). Where job seekers go will largely depend on work availability in these environments, which, of course, will vary geographically and over time. Even group size is changing over time, with unique otolaryngology practices on the decline and a trend toward larger practice size (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;6:1–6). Whether from competitive dynamics, practice expenses, or real-term decline in physician fee schedule payments, job creation through solo practice is waning. Therefore, job opportunities are increasingly set through the labor demand in these larger practice environments, which are based on things like referral volume, subspecialty need, and advanced practice provider (APP) integration. Of these items, referral volume is paramount for creating job opportunities. The upshot is that if referrals aren’t growing in a given practice environment, the preferences of a job seeker matter little—they have to take what’s available.

Medical Market Details

Before exploring competition for patient visits, we should take a step back and examine what competition looks like in a normal workplace market. In a normal market, competition occurs based on consumer value. Firms jockey to provide different products to different market segments at different costs. Better quality and/or lower cost usually wins, and the consumer wins. Transparency of quality and cost is vital to optimizing consumer value.

Unfortunately, we don’t operate in such a market. We operate based on referral control with hidden quality and cost. Worse yet, we have disparate payments for the same service based on service location, with asymmetric inflation figures applied annually by our government. In 2020, for example, Medicare paid the average hospital 2.3 times more money for a level 3 follow-up visit than they did an average private practice (American Medical Association Current Procedural Terminology code 99213, HCP Code Set G0463, CMS.gov 2020 payment files). Keep in mind, patients also pay that higher cost sharing for arguably the same service, and they have no idea how much they’re paying in advance. Normal markets don’t operate like this.

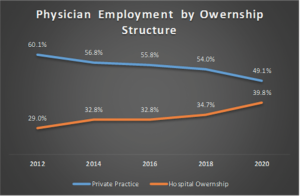

Medical payment disparities have persisted for decades despite site-neutral payment legislation and Medicare rules. They have allowed hospital systems to capitalize on arbitrage opportunities, motivating a consolidation of independent practices into their networks. We see this play out in the data. The American Medical Association produces physician benchmarking surveys every two years. The most recent iteration showed private practice employment had reached an alltime low, losses that were mirrored by gains in hospital employment (Kane CJ. Policy Research Perspectives. AMA. 2021) (Figure 1).

This shift toward an employed model has been more marked among primary care, with the same survey showing 58% of family practice and pediatrics in employed status in 2020. Practice acquisition has accelerated during the pandemic, with recent research showing a 38% increase in corporate owned practices between January 2019 and January 2022 (PAI-Avalere Health Report on Trends in Physician Employment and Acquisitions of Medical Practices: 2019-2021. April 2022).

These competitive dynamics and the resultant increase in healthcare costs are so remarkable that they are now being investigated by the Federal Trade Commission. And while surgical specialties have a higher level of private ownership, primary care represents the referral sources for subspecialty care. These referrals allow for pre-existing specialty practice growth and new service lines where they didn’t exist before. In other words, where primary care has already gone may be where subspecialty care goes in the future.

To the degree the willingness to supply labor has any real impact on choice of employment under various ownership structures, where will new graduates, who have hundreds of thousands of dollars of school debt, be more inclined to work? They’ll increasingly migrate to 501(c)(3) hospital entities where Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) will write off remaining debt balances.

Competition and Value

These market forces, however inefficient from a consumer value perspective, absolutely affect job availability and our workforce complexion. Luckily, the market has a knack for pushing back against inefficiencies. On the consumer side, price transparency tools and atypical means of establishing referrals without primary care involvement seek to disrupt the current construct. On the structural supply side, theoretical disruptive forces exist as well. In the past, when you had more generalists and a stronger private practice market, most would enter private practice or non-academic hospitals. When patients required subspecialty care referrals, they were sent where subspecialists were concentrated: academic centers.

Based on the structural mechanisms described above, academic and non-academic hospitals grew, and we’ve churned out higher proportions of fellows, who have increasingly gone to the competition of academic centers. In some markets this may have a negative feedback effect of pulling subspecialty referrals away from academic centers and decreasing training numbers, with the possible effect of suppressing training growth. Or, the opposite could happen: these hospitals are in alternative locations, build a critical mass of subspecialists, start their own residencies, and increase supply further. Since our GME growth is currently expanding at historic rates, this remains more theoretical, but it’s important to follow from a competition and supply perspective.

What remains clear is that, from the consumer perspective, competition currently isn’t geared toward maximizing value. As we jockey with each other in this inefficient market, we haven’t been exploring our workforce in detail and publishing this examination regularly for all to see so that market participants can make more efficient decisions for themselves. And we’ve been forgetting about where the real threat comes from in competition: not from the organization down the street, but from the outside—and that disrupts the normal way of things for all of us.

Future Workforce Design

To craft a more efficient healthcare system with more accountability and competition based on consumer value, we need systemic change that arises from lobbying efforts. Site-neutral payments and, more importantly, consumer price transparency should be the norm. We expect that of any other market interaction and service provided—why are we special?

Transparent outcome data, with appropriate controls, that patients care about should replace the current quality mandates put out by CMS. These transparency changes allow for more efficient allocation of capital— patients will go where they perceive the value is, and workforce changes will follow. Also, if taxpayers are footing the bill for PSLF, it should be curtailed to apply only to employment in access-challenged settings, regardless of the employer’s 501(c)(3) status. But these items aren’t under our control as a specialty.

As noted in part II of this series, we have a transparency problem—we don’t put out nuanced workforce information on a routine basis for market participants to digest. Just as a more value-transparent healthcare system allows for a more efficient patient allocation of capital, more transparent workforce information allows for a more efficient allocation of labor.

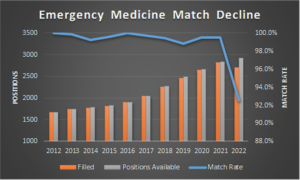

We recently saw the effect transparency can have on the supply side. Emergency medicine had an average match rate of 99.5% in the 10 years preceding the 2022 match. Yet in 2022, the year after their workforce report was published showing how dire the job market looked in the near future, not only did their match rate drop significantly to 92.5% but their absolute number matched did as well (National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: 2012-2022 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, DC. 2012-2022) (Figure 2).

Transparency allows for more nimble and efficient decision-making for market participants and is the only apparent remedy to the otolaryngology supply construct, which is also set up to produce an oversupply.

We must, however, do more to keep up with the dynamism of the market. Technological advances in medicine should be praised for bringing gains to the broader market, but we should recognize their potential for idiosyncratic disruption and plan accordingly. Technology is increasingly putting diagnosis and treatment decisions in the palm of our hands, disrupting traditional primary care treatment paradigms. It has brought us stent technology with disruption to the thoracic surgery workforce. Might we see the same with hepatologists and liver transplant surgeons with effective hepatitis C drugs? Or in the field of gastroenterology with cancer screening tools like Cologuard? Are we not being disrupted currently by HPV vaccines and biologics for sinus disease? In the face of these disruptive forces, we can only plan for downside risk protection with buffer systems.

Within individual practices, APPs allow a buffer for practice continuation. They can join another specialty practice tomorrow—we can’t. Training buffers allow for resident case protection in the event of case declines for whatever reason. Retraining systems, which would allow for rebuilding generalist skillsets, allow for protection of those who face idiosyncratic risk in the future, or if we find ourselves with a glut of subspecialists who can’t find meaningful work. These last two buffers exist in private practice and nonacademic hospitals, and academic departments would be wise to engage them now.

Final Thoughts

More than anything, I hope this series generates a discussion and motivates us to come together to think of a better path forward for the betterment of our patients and our specialty. No one person has all the answers—this discussion and execution will need to involve all of us. We need to get our workforce right. Doing so affects whether we can serve our mission with grace, improve quality and our patients’ lives, and maintain a meaningful practice. Leadership on these issues now will pay dividends in the future and bring us closer as a specialty.

Dr. Tompkins is a private practice otolaryngologist in Columbus, Ohio.