© Polsole / shutterstock.com

Events this past spring and summer, beginning with the death of George Floyd—a Black man killed during an arrest that sparked protests against police brutality—showed that many Americans want greater efforts to mitigate racism in the United States.

Explore This Issue

October 2020People from a broad spectrum of ethnicities and backgrounds responded to the call for action. Like many others, people in the medical industry, including those in otolaryngology, were inspired to act in a variety of ways.

The Impact of George Floyd’s Death

Brandon Esianor, MD, a resident physician in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, for example, felt compelled to raise awareness of racial injustice within the Black community by organizing a Day of Silence with a few other residents. “We welcomed members of the Vanderbilt family, including residents, attendings, staff members, and patients and their families, to select specific time slots to kneel outside for 8 minutes and 46 seconds in honor of George Floyd’s life,” said Dr. Esianor. “During the demonstration, participants held up the names of individuals whose lives have been lost at the hands of police, and we passed out lists of different resources, such as movies, books, and websites, that people could use to learn more about racial injustice among the Black community and how they could serve as allies for those who are most affected.”

The event was a huge success, with more than 1,000 participants. It also helped spark the creation of a task force at Vanderbilt geared toward ensuring that momentum for change is maintained. Dr. Esianor, co-president of the Minority House Staff organization, is working with the task force to plan another event geared toward raising awareness of injustices within the Black community, including health disparities.

George Floyd’s untimely death also sparked a reaction from Noriko Yoshikawa, MD, a senior physician and assistant program director in the department of head and neck surgery at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif. “After his murder, residents and attendings had an educational session dedicated to racism in America,” she said. “Our medical center had even larger discussion circles in which Black colleagues shared their personal experiences of racism and reactions to current events. We’ve also started discussions on allyship, because there has been a lot of interest from those who previously haven’t dealt much with racism.” Furthermore, a plethora of hospital-wide grand rounds addressed racism in medicine, systemic racism, and the health effects of racism.

Following George Floyd’s death, Shannon D. Fayson, MD, a resident surgeon in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, says the university’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) Committee held an open-forum virtual meeting at which several people shared emotional personal accounts of racism. “We discussed how we could all contribute to creating an anti-racist culture in our department,” she said. “We received many positive messages from attendees who appreciated the authenticity and vulnerability shared during the meeting. Racism is a sensitive topic that many people choose not to discuss. However, I believe when people hear about racism’s painful effects from people they love and value, they can transiently feel their pain, and that experience makes them want to take a stance against injustice.”

I believe when people hear about racism’s painful effects from people they love and value, they can transiently feel their pain, and that experience makes them want to take a stance against injustice. —Shannon D. Fayson, MD

Dr. Esianor also organized an informal discussion among his resident cohorts to discuss recent events. “People who may not know as much about racial injustice among the Black community had the opportunity to ask questions,” he explained. “As a Black man, I was able to share some of my personal experiences. I thought there was a need to break the ice and discuss these matters together, as we’re a close-knit group. If we can’t have these conversations among ourselves, who can we have them with?”

Ongoing Initiatives

Although George Floyd’s death was a wake-up call for many, anti-racism efforts certainly aren’t anything new among medical institutions. Kaiser Permanente has had an equity, inclusion and diversity committee for decades. In Dr. Yoshikawa’s department, trainings have included topics on implicit bias, cultural humility, and the myth of meritocracy, grand rounds talks have focused on the history of racism in medicine, and book clubs have used literature to examine the intersection of healthcare and culture.

University of Connecticut otolaryngology residents David Wilson, MD, and Roshansa Singh, MD, (standing second and third, from right, respectively) and Lawrence Kashat (seated row, second from right) participating in the White Coats for Black Lives movement during the June 6, 2020, BLM March in Hartford, Conn.

© Courtesy Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD

Work by Carrie L. Francis, MD, associate professor in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the Kansas University School of Medicine in Kansas City, and her colleagues has been ongoing for years. Some of their most significant and longitudinal initiatives include a biennial simulation otolaryngology open house event that allows medical, post-baccalaureate, and undergrad students to experience common otolaryngology procedures. This event is co-sponsored with two student groups that support students of color traditionally underrepresented in medicine and that advocate for the health needs of underserved communities and communities of color. As a result, more medical students of color are introduced to otolaryngology early in their journey.

Other initiatives include developing funded research and clinical electives. In an effort to enhance DEI efforts, Dr. Francis developed a lectureship that offers a campus-wide opportunity to share diversity and inclusion efforts, as well as health equity expertise, with the healthcare system and community.

Keith A. Chadwick, MD, MS, who earlier this year was a Sean Parker Fellow in laryngology at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City and is now an assistant professor in the department of surgery, division of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery, at Stony Brook University in Stony Brook, N.Y., said that numerous efforts at Weill had been underway for decades to promote anti-racism and inclusion, and many have ramped up in response to current events. The Weill Cornell Medicine system took several immediate steps to actively combat systemic racism during his time there, including:

- De-escalating the systems-wide use of the New York Police Department’s police force.

- Making anti-bias training mandatory for all faculty and staff.

- Encouraging departments to lead their own workshops on fostering anti-racism and diversity, and creating a sense of belonging.

- Strengthening the Office of Diversity and Inclusion by appointing an administrative director.

- Starting an anti-racism student task force to enact changes in the medical education system.

- Appointing diversity champions and requiring annual diversity effort reports for all academic departments.

- Increasing recruitment efforts of underrepresented faculty and trainees through new policies and action plans in hiring and promotional efforts.

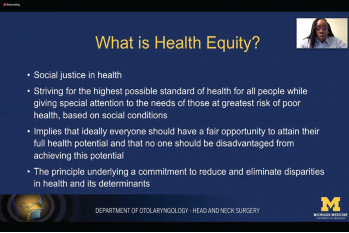

The DEI committee at the University of Michigan meets once monthly to offer a safe space to share personal experiences, educational resources, and DEI initiatives to help combat racism, support health equity, and support inclusion within the otolaryngology community, Dr. Fayson said. In addition, Michigan Medicine’s Office for Health Equity and Inclusion and the Graduate Medical Education Office launched a Healthcare Equity and Quality Scholars Program for trainees last summer. The 14-month program addresses cultural humility and social determinants of health as well as foundational instruction on quality improvement.

The otolaryngology community at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine in Farmington, Conn., has participated in various institutional initiatives whose primary objectives are to increase representation of underrepresented minorities in medicine (URIMs), said Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD, professor and residency program director in the department of surgery, division of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. For example, for nearly two decades, UConn’s Health Career Opportunity Programs (www.health.uconn.edu/hcop/) have served as a continuous pipeline for middle school, high school, and college students of diverse backgrounds to become future doctors, dentists, and health professionals.

We will make mistakes, and when we do, we have to be open to feedback, even if it stings, and make earnest efforts to do better. If we allow ourselves to stay quiet, then we allow racism to continue. —Noriko Yoshikawa, MD

Otolaryngology faculty have been active participants, offering mentorship in the clinics, operating room, and research laboratories. The UConn School of Medicine has been recognized by US News & World Report for its success as one of the top 10 medical schools with the most African-American students. This success extends to graduate medical education, where nearly 13% of residents and fellows are URIMs. Traditionally, the otolaryngology residency program has had an excellent balance in male/female representation, with LGBT, multiple ethnic groups, and five religions also represented. To increase URIM representation, the otolaryngology program has been active in undergraduate education through the creation of an interest group and engagement with local chapters of the Student National Medical Association and Latino Medical Student Association.

In another initiative, Dr. Esianor and a few other residents organized a virtual introduction to the otolaryngology specialty geared toward minority students, collaborating with institutions nationwide to teach these students about what the specialty has to offer and why they should consider it. The event, which drew 120 medical students, was a success thanks to collaboration among residents across the country and advertising on platforms like Instagram and Twitter. “It was helpful for medical students to see people who look like them working in the ENT field,” he said. “It solidifies for them that they, too, can one day be in our position.”

Overcoming Hurdles

Dr. Shannon Fayson presenting on Health Equity Advocacy, along with Dr. David J. Brown, at University of Michigan’s Virtual Subinternship on June 13, 2020. Photo by Ramsha Akhund.

There are many barriers to combating racism and promoting inclusion in the medical community that also affect otolaryngology. One issue is that racist policies and procedures have become so ingrained in systems that they can be challenging to undo, Dr. Chadwick said. The best way to overcome this problem is for leaders to actively make a dedicated effort to evaluate potentially biased policies and replace them with more inclusive ones.

Dr. Yoshikawa believes that well-intentioned people are often paralyzed by the fear of saying the wrong thing or offending the person they want to help. “We will make mistakes, and when we do, we have to be open to feedback, even if it stings, and make earnest efforts to do better,” she said. “If we allow ourselves to stay quiet, then we allow racism to continue.”

The bottom line is that combating racism takes an incredible amount of courage, tenacity, empathy, and innovation. “Some people won’t want to speak up because it will disturb the peace or they may feel inadequate to fight for justice because they cannot fully relate to the barriers minorities have to overcome,” Dr. Fayson said. “Whatever the hurdle may be, keep fighting for equity. You’ll make people uncomfortable when combating racism, but real growth occurs when individuals are pushed outside of their comfort zones.”

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer based in Pennsylvania.

Initiating Anti-Racism Efforts

How do you begin anti-racism initiatives at your own facility or practice? Otolaryngologists offer some advice.

Identify and Evaluate. The first step in combating racism is to identify it, said Keith A. Chadwick, MD, MS, an assistant professor in the department of surgery, division of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery, at Stony Brook University in Stony Brook, N.Y. “The best way to do that is for institutions to offer mandatory training and workshops in bias, privilege, diversity, inclusion, anti-racism, and allyship,” he said. “However, it’s also important that institutional leaders evaluate their policies and procedures to determine what systemic barriers exist that prevent all groups from being equally represented and recognized. It may be worthwhile to examine other institutions that have had success in diversity efforts and adopt some of the same policies and principles.”

Engage and Empower. At Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Brandon Esianor, MD, a resident physician in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery, says getting leadership at the top to create and support committees that include people from diverse backgrounds who can work toward the common goal of diversity and inclusion has been effective. It’s also important to engage and empower people who are passionate about these matters at all levels of employment.

Start the Conversation. Shannon D. Fayson, MD, resident surgeon, department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, recommends that programs begin initiating discussions about racism, implicit bias, and health disparities within their departments. “Some people may not want to participate, but these discussions are still important because racism happens everywhere, affecting the way people perform in work environments and their overall well-being,” she said. “Silence and neutrality are damaging. People must also accept their privileges and understand the impact of systemic racism on minority trainees, faculty, and patients. Once this happens, a department can then develop policies and initiatives through an equity lens to combat racism as well as to improve the experience of these groups.”

Be Comfortable with Discomfort. Ultimately, you need to be willing to be uncomfortable, said Noriko Yoshikawa, MD, a senior physician and assistant program director at Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif. “We have to keep our eye on the goal of combating racism and be willing to consider if we might be part of the problem,” she said. “We need to approach this inquiry with curiosity and kindness, not with guilt and shame. None of us created this system. This pot has been stewing for centuries, but now that we’ve found ourselves in it, we need to figure out how to turn off the heat.”