Value-based care (VBC) may not seem relevant to most otolaryngology practices today, given that many remain mired in a fee-for-service (FFS) payment model that annually reduces reimbursement for clinical services to levels below the rate of inflation and also reduces the perceived value of the specialist delivering those services.

Value-based care (VBC) may not seem relevant to most otolaryngology practices today, given that many remain mired in a fee-for-service (FFS) payment model that annually reduces reimbursement for clinical services to levels below the rate of inflation and also reduces the perceived value of the specialist delivering those services.

But VBC is coming to otolaryngology offices within the next five years through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) initiatives, and otolaryngology needs strategies for responding to how value, outcomes, and cost will be captured and measured, both currently and in the future, said Willard C. Harrill, MD, a clinical advisor for the PACES Center for Value in Healthcare and a member of the Physician Payment Policy Workgroup for the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNSF).

“VBC is an opportunity to regain much of what we lost in FFS, but we will surrender the opportunity to define value and distinction for our specialty within this new payment paradigm if we do not focus on what is coming our way now,” Dr. Harrill said.

In an interview with ENTtoday, Dr. Harrill identified several key steps the profession needs to take to prepare for this watershed event, which is marked by evolving payment and quality metrics. He drew not only on his work with these groups but also on his experience co-founding BridgepointMD, a partnership that provides specialty physician group practices the expertise and data technology needed to navigate alternative payment models (APMs).

Building a Better Infrastructure

One of the most important tasks for otolaryngology is to build a better translational infrastructure and workflow that captures the value the profession delivers within claims-based analysis measures (CBAMs), Dr. Harrill noted. CMS, which processes $2.4 billion a day in Medicare claims, has determined that the only current interoperable solution for “value” transparency on that scale is through CBAMs. But there’s a problem, he said: CBAMs do not sufficiently weigh outcomes-based analysis measures (OBAM) when calculating value. Fortunately, within five years, increased OBAM transparency likely will come from evolving electronic health record (EHR) and health information exchange interoperability standards, he noted.

That process will be hastened by Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standards, which were developed in 2012 by a nonprofit group as a better system for exchanging healthcare data between different computer systems, he noted. “FHIR will provide structured data transparency to capture next-generation quality and outcomes measures on an entirely different level in the next five years,” Dr. Harrill said. “That is the future.”

Make no mistake, he added: “If physicians do not lead in the development of condition-specific OBAMs, the payers will, leaving physicians once again on the sidelines in a race to the bottom, as is the case with FFS.”

Dr. Harrill called on the AAO-HNSF, the Triological Society, and other specialty groups “to collaborate in retooling clinical guidelines and quality outcome measures as validated components for OBAM, based on our scope-of-knowledge expertise.” Without such efforts, “this will be done by another third party that does not have our expertise tied to real patient experience.”

Nailing Down Risk-Adjusted Scores

Otolaryngology also needs to work on accurately documenting capturable data within an episode of care and defining the patient’s risk-adjusted factor (RAF) score, which measures predictable spending risk within the management of a clinical condition, Dr. Harrill noted. RAF scores represent the patient’s disease severity, chronic comorbidity, surgical risk, and other critical factors that translate to higher expenditures within the patient’s care journey. Without such information, physician cost variability within episodes of care “can make you look like a ‘bad physician,’ or at the least an overutilizer, which in the eyes of most payers is basically the same thing,” he said.

So, what is the best solution? “The only way to capture disease severity in a structured, interoperable place in your clinical notes is via your clinical assessment and plan coding,” Dr. Harrill said. “That is the source for RAF analysis and episode TCOC [total cost of care] standardization within a claims-based analysis by the payers.”

You have to have the data documentation and analytics infra-structure in place to tell the patient’s acuity story through ICD-10 coding.” — Willard C. Harrill, MD

One of the best tools to use in achieving this higher level of documentation is the relevant International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), listing chronic co-morbid conditions “that may affect a patient’s otolaryngology journey within given care path-ways to accurately predict TCOC,” he added. “If your patient has hypertension or diabetes, or if they are on an anticoagulant or have had a prior cardiac event or any other condition that would affect the morbidity and mortality risk of the condition you are treating within an episode of care, you need to record those conditions as an ICD-10 entry in the assessment section of your SOAP [subjective, objective, assessment, and plan] notes.”

Dr. Harrill stressed that this approach to clinical documentation gives payers what they need to accurately measure value. “Remember, no payer is looking at the uncoded past medical history section of your note, because that is not structured data for machine reading,” he said. “You have to start recognizing now where to put that information in your EHR so that it has transparency to the system. Also, this is not ‘code stacking,’ because only relevant diagnoses matter, such as defined hierarchical care codes [HCCs].” (For more on code stacking, see sidebar.)

He added that “the carrot was laid out for specialists” to bolster patient condition and risk transparency reporting within their medical records and claims billing when CMS updated its evaluation and management (E&M) clinical decision-making standards in 2023. “This shifting emphasis to assessment and plan coding guidelines for FFS parallels the claims-based assessment being built out for episodes of care in VBC,” he said.

Dr. Harrill stressed that “RAF coding is one of the biggest problems now for otolaryngology. We’re where primary care was 12 years ago when it comes to under-reporting patient risk and projected cost of care,” he said. “The good news is we have time because our specialty is on the back end of the VBC integration curve. We can use this time wisely to adopt VBC best practices,”

he stressed.

“Equally important is the defining of outcomes and quality for our specialty and translating that into standards that will be captured and translated

to payers.”

Four Payment Pillars

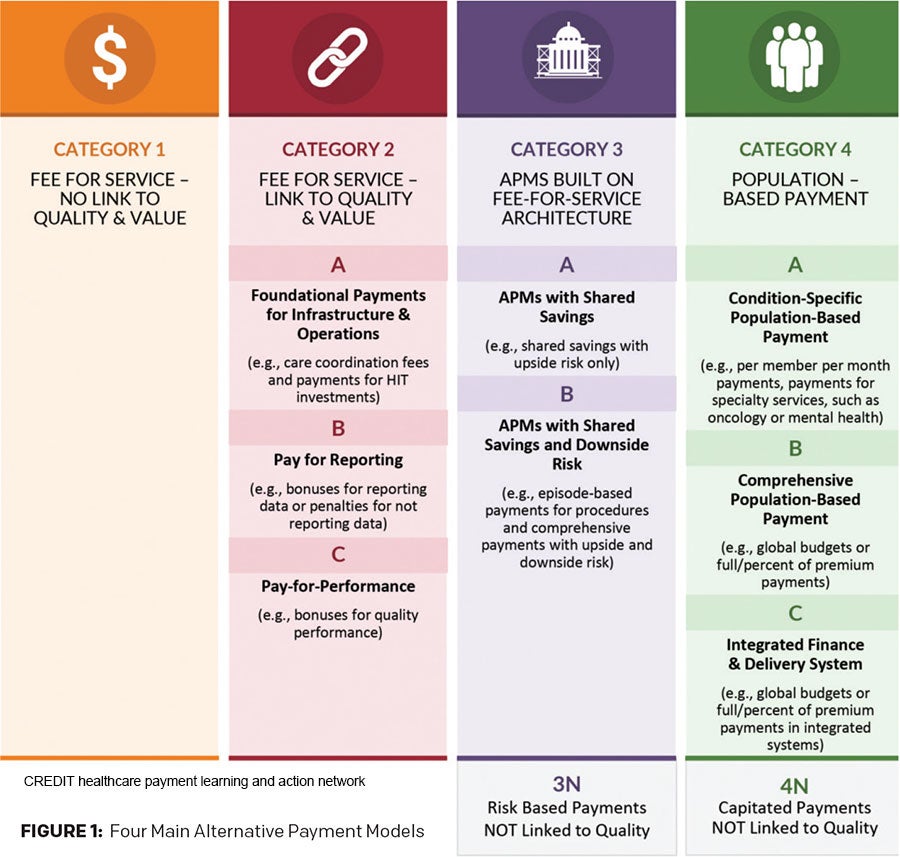

Becoming VBC ready also hinges on knowing which value-based payment model most affects otolaryngology, Dr. Harrill noted. For that answer, he suggested looking at a framework developed by the Healthcare Payment Learning and Action Network, a group of public and private healthcare leaders that is working to increase APM adoption. The framework (Fig 1)divides APMs into four main categories: traditional fee-for-service, fee-for-service that is linked to some quality and value metrics, alternative payment models that include shared savings with varying levels of risk among stakeholders, and population-based payments (Figure 1). There is a veritable alphabet soup of VBC and APM models within that framework, but for otolaryngology, “know that we are firmly in category 2,” he said.

The reasons why are varied, but it essentially comes down to the fact that “our potential savings per patient episode is not that great to be able to share in upside and downside risk,” based on the TCOC for a typical otolaryngologic condition. With other specialties, he noted, one acute hospitalization can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and there are multiple ways to impact spend variability for those individual episodes of care. With otolaryngology, in contrast, “our overall spend for chronic sinusitis, for example, is pretty big. It’s just a shallow spend per patient, albeit a very large collective spend for the population. So we still need to find value within that bandwidth.”

The reasons why are varied, but it essentially comes down to the fact that “our potential savings per patient episode is not that great to be able to share in upside and downside risk,” based on the TCOC for a typical otolaryngologic condition. With other specialties, he noted, one acute hospitalization can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, and there are multiple ways to impact spend variability for those individual episodes of care. With otolaryngology, in contrast, “our overall spend for chronic sinusitis, for example, is pretty big. It’s just a shallow spend per patient, albeit a very large collective spend for the population. So we still need to find value within that bandwidth.”

Head and neck cancer episodes in otolaryngology are a definite exception. Typical head and neck cancer cases, Dr. Harrill explained, involve enough spend variability to “slide nicely” into category 3 bundle payments with the right predictive analytics. “But again, you can’t engage these models unless you understand claims-based analysis and patient RAF scoring,” he stressed. “And that first step is to be able to perform well in the category 2 model care coordination and first-generation quality reporting payment models. For that, you have to have the data documentation and analytics infrastructure in place to tell the patient’s acuity story through ICD-10 coding.”

This urgency is justified, he noted, because “the wheels are already in motion. Whether we like it or not, the market is beginning to build out VBC scorecards to judge us based on our cost variability for a given diagnosis or procedure we’ve recorded in our EHR and claims systems.

Bringing focus to preventing burnout during the transition period will be critical in the intelligent design of VBC programs.” — George A. Scangas, MD

“Make no mistake, we will be measured against our peers, which is why if you don’t accurately describe that patient’s comorbidity risk, you are under-coding the RAF score of your patient,” he continued. In such a scenario, “your cost benchmarks become out of balance to the reality of the patient’s condition that attributes to the final cost of care.”

As for other steps the otolaryngology profession must take, “Right now, as noted, we are firmly a category 2 specialty,” Dr. Harrill said. “So, what documentation and billing infrastructure do we need to progress beyond that? What partnerships do we need to forge? If we address just that alone in the next five years, our profession will be in a very strong position when some of these currently voluntary VBC programs become mandatory.”

In that scenario, “we’ll have the data transparency systems and otolaryngology-developed clinical measures in place to become high-performing VBC physicians.”

Patients, Payers, and Burnout

George A. Scangas, MD, an assistant professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Massachusetts Eye and Ear at Harvard Medical School in Boston, stressed that although VBC discussions often focus on complex cost/value equations, “at the core of VBC is a focus on person-centered, coordinated care. Often physicians hear from patients with complex or undiagnosed medical conditions how they wish their providers would communicate more freely across medical organizations. And they are right.”

Otolaryngologists, Dr. Scangas continued, “often treat complex medical conditions that require interdisciplinary collaboration for optimal outcomes. This requires deliberate, time-consuming, and non-reimbursable efforts. A system that rewards such collaboration should benefit individual patients and, hopefully, also decrease physician burnout rates.”

The value expression for specialty care will [be driven by] the specialists defining the limits of what their expertise can do.” — Frank Opelka, MD

“Bringing focus to preventing burnout during the transition period will be critical in the intelligent design of VBC programs.”

Frank Opelka, MD, the immediate past medical director for quality and health policy at the American College of Surgeons, offered a caveat when trying to define VBC. “Value-based healthcare means something different to every stakeholder,” Dr. Opelka said. “No matter who you ask, almost no one has it right. They just have FFS with tacked-on measures that are tied to a transaction. It is not value until the individual seeking care knows how and where to find the care that meets their goals and that is safe, affordable, and equitable.”

Dr. Opelka, founder and chair of the PACES Center and a founding member of the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network and the Surgical Quality Alliance, also cautioned against placing too much faith in the managed care side of the value equation. “Value will not be defined well by a payer, whose only interest is retaining their clients and their margin,” he said. “It will not be defined by surgeons either; we are too close to the applied medical science and too far removed from determining the patient goals of care and if those goals were attained.”

So, where will workable definitions of value come from? “The value expression for specialty care will [be driven by] the specialists defining the limits of what their expertise can do,” he said. “That includes the primary care physician who agrees that the care would be of value to their patient, and from the patient who says if I had to do it all over again, I would,” he said. “That’s value— not some payer-defined standards.”

David Bronstein is a freelance medical writer based in New Jersey.

Disclosures: Dr. Harrill is a co-founder of BridgepointMD. Dr. Opelka is a consultant for the American College of Surgeons, KPMG/State of Colorado, and Third Horizons Strategies. He is the founder and principal of Episodes of Care Solutions, LLC.

Lessons from a Bundled Care VBC Model

Because there are several value-based care (VBC) programs and evaluative reports available, it’s important to determine which ones hold lessons for otolaryngology, Dr. Harrill noted. One good place to start is CMS’s Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BCPI) Advanced 5th Annual Report, which was released in June 2024 (https://www.cms.gov/priorities/innovation/innovation-models/bpci-advanced).

According to CMS, this is the first report assessing the BCPI model after significant changes were implemented in Model Year 4 (2021) to bolster care quality and savings. Initial results seem promising: according to the report, the program’s net savings in Model Year 4 ($464.7 million) were larger than the losses in Model Years 1 through 3 combined ($179.5 million in losses). But a glance at the report shows that none of the specialty procedures listed involve anything otolaryngologists do for patients. So, why is it worth the profession’s time to pay attention?

“The BCPI report makes it very clear that to effectively engage in bundled payments, you need a strong documentation and billing infrastructure for care pathway analysis and performance analytics based on these new VBC metrics,” he said. “That’s the best way to determine who is a high value-based performing physician and who is not.” The challenge, he noted, is that many physicians “don’t have access to total cost-of-care data to run these analyses and access this critical feedback and improve their individual performance curves.”

Help can come from one of two areas: being part of a health system that will run these VBC analytics systems for you or hiring a VBC “enabler” consultant if you are in an independent group practice. (VBC enablers help providers transition from fee-for-service into value-based payment models by providing wraparound technological, administrative, and clinical resources.) But Dr. Harrill offered a caveat on consultants: Some will suggest code stacking. “That’s not the right approach,” he said. A better method, he said, is to use codes strategically so that they are relevant to your patient, including the 80 or so hierarchical condition category (HCC) codes that are used for claims-based analysis in many VBC models. Since 2004, HCCs have been used by CMS as part of a risk-adjustment modeling that identifies individuals with serious acute or chronic conditions. “The ENT profession needs to begin to understand HCCs and how they fit into the VBC equation,” Dr. Harrill said.

Bundled Payments 2.0

As for whether ENT practices are ready for bundled payments today, “there’s two meanings to bundle payments that we need to understand,” he noted. “There are otolaryngologists doing procedural bundled payments right now.” These same-day bundles, he noted, pay one price for the procedure, facility fee, and ancillary care. “It’s a very common model that’s good for high-deductible plans such as employer plans that want to avoid wider spend variability.”

Once value-based concepts such as longitudinal risk-sharing get added to bundled care, however, that’s where things get complicated for otolaryngologists, Dr. Harrill noted. For procedures such as sinus surgery or tonsillectomy, there are limited variations in TCOC to manage. As a result, 90-day total cost-of-care bundled risk-sharing plans usually are not viable for otolaryngologists.

“If you did a bundled payment for tonsillectomy under a 90-day total cost-of-care liability, one hospital admission may blow out your entire profit margin for the year,” he said. “We know that Medicaid tried a tonsillectomy bundle payment program in several states about 15 years ago, and it was a disaster. Why? There’s not enough savings in the system for a bundle arrangement to accept total cost-of-care liability.”