In a modern society that is constantly “on,” with 24-hour news channels, Internet connection, cell phones, video games, and a rapid pace of life unequaled in previous generations, sleep deprivation and sleep disorders are not only a risk—they are a given. Inadequate sleep may even be the next big public health outcry in the U.S., according to Suzan Garetz, MD, of the Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor, Mich.

In such a stimulated, saturated society, children and adolescents are not exempt; indeed, they can suffer the most, particularly if their symptoms of daytime sleepiness are not correctly diagnosed and treated. Otolaryngologists, who often see children and adolescents with daytime sleepiness in whom sleep disordered breathing (SDB) is suspected, need to consider other reasons for daytime sleepiness in order to accurately and adequately treat the whole child.

Although the most common reason for sleepiness in children and adolescents is insufficient sleep caused by poor sleep hygiene, other conditions may actually be to blame and could confer substantial harm if not correctly identified.

Know Thy Sleepiness

“Often otolaryngologists evaluating sleep disturbances in children and teens will focus on sleep apnea and not delve into other possible sleep problems,” Dr. Garetz said. “As otolaryngologists, we also need to be aware of other conditions causing sleep disturbances in that population.”

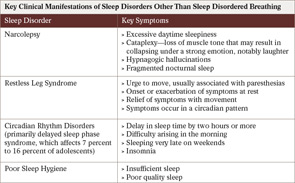

Among the most common sleep problems that occur, either alone or in conjunction with SDB, are poor sleep hygiene and circadian rhythm disorder (or delayed phase sleep). Less common are narcolepsy and restless leg syndrome, both of which can carry a high morbidity if not correctly diagnosed.

According to David Gozal, MD, a pediatric sleep specialist and physician-in-chief at Comer Children’s Hospital at the University of Chicago Medical Center in Chicago, the easiest way to approach the challenging task of determining the cause of daytime sleepiness in children is to recognize that sleep disorders basically fall into three categories: 1) children who get sufficient sleep but still have daytime sleepiness (e.g., narcolepsy); 2) children who get insufficient sleep and are sleepy (e.g., poor sleep hygiene, circadian rhythm disorder); and 3) children who are sleepy because of disruptive sleep (e.g., SDB, restless leg syndrome).

“We try to look for clues that will give us some answer to whether we’re dealing with one of these three categories and then we look in more detail into which category it is,” Dr. Gozal said.

Clinical Assessment

Taking a thorough history of the child or teen is the first critical step in diagnosis. Important questions to ask include how much sleep the child gets, what time the child goes to bed and wakes up, and what manifestations of sleepiness occur during the day.

According to Carole Marcus, MD, attending physician and director of the Sleep Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, it is important first to distinguish sleepiness from fatigue or tiredness. “Sleepiness really means the propensity to fall asleep, whereas tiredness may indicate a lack of energy which can be related to many things, such as anemia or depression,” she said.

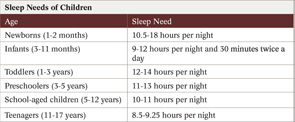

To take a thorough history, Dr. Marcus and her colleagues send out a sleep diary to all patients prior to their clinical visits in order to obtain documentation of sleep patterns. These diaries, she said, provide clues about what may be causing the daytime sleepiness. Key clinical features described in a patient’s history and diaries may provide clues toward a differential diagnosis (Table 1). In some cases, these clinical symptoms are sufficient for a diagnosis. This is particularly true for sleepiness related to poor sleep hygiene and circadian rhythm disorders and, in many cases, for restless leg syndrome. Further evaluation is necessary, however, for suspected cases of narcolepsy and in some cases of restless leg syndrome.

Further Tests

“Any time you have a child with significant daytime sleepiness, I would do a sleep study and if the sleep study does not show apnea, I follow it with a daytime Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT),” Dr. Marcus said. “That is the test for narcolepsy at the moment.”

Stating that this is the common practice at her clinic, Stacey Ishman, MD, assistant professor of Otolaryngology-Hed and NEck Surgery within the Division of Pediatric Otolaryngology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, emphasized that the importance of recognizing manifestations of narcolepsy and doing the follow-up MSLT is highlighted by the fact that this disorder remains largely under-recognized among otolaryngologists.

“Part of the problem with diagnosing narcolepsy is that we are not attuned to it,” said Dr. Ishman, adding that it is not uncommon for people to go without a proper diagnosis for a couple of years, because it is a disorder that tends to become more apparent in older adolescents and adults. Yet she has diagnosed and treated kids as young as 10 or 11 with narcolepsy.

Narcolepsy is suggested as the diagnosis on the MSLT by objective measures that show short sleep latency and sleep fragmentation, as well as the presence of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep at the onset of sleep, which, according to Dr. Ishman, is the defining feature seen on the MSLT.

Further evaluation may also be necessary for children with suspected restless leg syndrome. Although restless leg syndrome is predominately diagnosed by clinical symptoms, a sleep study may be helpful when there is doubt, according to Dr. Marcus. “This is especially true in young children in whom it is hard to get a good history,” she said, adding that a sleep study can help differentiate between normal restless sleeping movements and the periodic limb movements that are usually associated with restless leg syndrome.

Dr. Ishman also suggested getting an iron profile on children with suspected restless leg syndrome; this treatment may control symptoms in children whose serum iron, transferrin, and ferritin levels are on the low end of normal or below the normal range. “It has been shown that people with low iron levels can be treated with iron, and their restless leg symptoms will go away or be controlled,” she said.

Dr. Gozal urged otolaryngologists to take symptoms of sleepiness very seriously and not rule out persistent sleep problems, even in children surgically treated for sleep apnea. “If there are ongoing symptoms, it should not be assumed that just because surgery was performed it was effective,” he said, adding that surgery can take away the snoring but not the disease. ENTtoday

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a medical writer based in St. Paul, Minn.

Leave a Reply