Microvascular free tissue transfer for facial reconstruction, commonly known as free flaps, represents a clear advance in the reconstruction of large facial defects caused by head and neck tumors, trauma or congenital defects. Both cosmesis and function have greatly improved in patients who undergo this procedure, compared with prior treatments of these large defects that relied on suturing together tissues surrounding the defect, which left patients dealing with long-term cosmetic and functional complications.

One clear way to measure this advance is to examine patient outcomes in head and neck cancer patients. According to Daniel Alam, MD, head of the section of facial aesthetic and reconstructive surgery at the Head and Neck Institute Cleveland Clinic in Ohio, the data over the past 50 years on head and neck cancer show that, despite a lack of dramatic change in survival, patient outcomes and patient functional endpoints have improved dramatically from what they were 20 years ago. “A great part of that,” he said, “has been the improvement in how we do reconstruction.”

How has facial reconstructive surgery changed over the years with the use of free flaps, and what issues may be on the horizon due to its success and expanded use?

Free Flaps: Revolutionary and Evolutionary

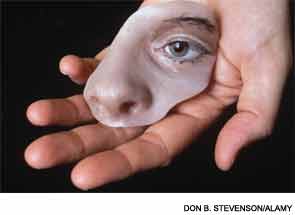

Prior to the introduction of microvascular free tissue transfer in the 1960s and 1970s, reconstruction treatment of large facial defects caused by head and neck cancers or trauma relied on the use of regional pedicled flaps that often left patients with permanent cosmetic and functional defects. Microvascular free tissue transfer enabled physicians to rebuild large anatomical areas that were missing due to a tumor, trauma or congenital defect by using tissue from one part of the patient’s body for use in reconstructing the defect.

“Free flaps are basically a transplant of a patient’s own tissue from one part of the body to another part, and the reason they are called “free” is that the vessels are detached at the primary location and then moved to another spot,” said Dr. Alam. For example, if someone has lost a part of their jaw because of cancer, bone can be taken from the patient’s leg along with the blood vessels and blood supply and transferred to the jaw in a free fashion to rebuild the jaw.

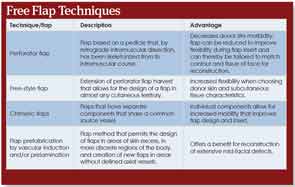

The ability to do this type of autogenous vascularized transplant has, according to Dr. Alam, “revolutionized facial reconstruction surgery.” Additionally, the application of free flaps has evolved over the years, with the refinement of tissue harvest and flap design technologies (See “Free Flap Techniques,”).

According to Mark K. Wax, MD, director of the microvascular fellowship program at the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland, free flaps were initially used rarely because of their technical difficulty and the need for surgical expertise. As technology and surgical expertise have improved, he said, the success rate has risen to greater than 96 percent. Since the 1980s, he said, the failure rate has dropped from about 30 percent to between 1 and 3 percent at large centers.

Downsides and Limitations of Free Flaps

Despite the reduction in failure rates over the years, Dr. Alam emphasized the fact that facial reconstruction with free flaps is a procedure with a defined failure rate. “If a failure occurs, a revision needs to be done with a long hospitalization associated with it,” he said.

He also said that there are limitations to what can be done with free flaps, citing the difficulty of using them to reconstruct complex neuromuscular defects like total glossectomies.

For Terry Tsue, MD, physician-in-chief at the University of Kansas Cancer Center and the Douglas A. Girod, MD, endowed professor of head and neck surgical oncology at the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Kansas City, a potential downside of the procedure is the effect the procedure has on the part of the body from which the tissue is taken to use for the autogenous transplant. “When you take tissue from one part of the body that is not giving a person a problem to repair the head and neck, there is always the potential for influencing the function of the arm, leg or back from which you took the tissue,” he said. However, he said that the head and neck area is such an important part of the body in terms of hygiene, personal image and aerodigestive function that the potential effect on other parts of the body is worth the sacrifice.

The biggest limitation of using free flaps is the expertise of the surgeon and the microvascular peri-operative care team, he said, emphasizing the importance of developing the necessary skill and knowledge set to perform the procedure well.

The importance of surgical expertise in overcoming the limitations of the procedure was also cited by Dr. Alam, who speculated that the reduction in failure rates was probably due to increased surgical experience. He likened it to thyroidectomy, which carried a high mortality rate and complication rate when it was initially used in the 1920s but has been considered a routine procedure since the 1980s.

Potential Issues

As the United States continues to move toward a value-based health care model, the question of cost may become an issue, given the high upfront costs of the procedure. While allowing that the procedure is expensive at face value, Dr. Alam emphasized that free flaps offer a far more efficient way to reconstruct large defects than other flaps. He and his colleagues at the Cleveland Clinic have done many metric analyses of the procedure, he said, that show that better outcomes are achieved with free flaps versus conventional procedures in terms of cost containment and patient outcomes.

“The future of free flaps is solid,” he said. “The indication is growing, and it is a growing specialty and, as with all growing specialties, it will need checks and balances to ensure appropriate use. That is the natural growth of a specialty.”

For Dr. Tsue it is very simple. “The functional outcomes [with free flaps] speak very loudly,” he said, adding that he sees only an expansion of the indication for the procedure. He emphasized, however, that physicians are still trying to come up with more efficiencies to shorten the operative time.

According to Dr. Alam, this outcome has been achieved. “We have reduced hospitalizations from what used to be 10 to 14 days or longer to mostly seven to 10 days,” he said, adding that if conventional flaps are used on patients with large defects, they often require multiple surgeries to achieve the same goal.

As of now, however, Dr. Wax emphasized that cost is not an issue, because the free flap procedure, is not an elective procedure and getting patients approved for it is no more difficult than it is for many other procedures that are done.

Future Trends in Free Flap Surgery

One interesting area of investigation that may affect the future use of free flaps, according to Dr. Tsue, is the increasing use of endoscopic resections with robots and lasers, which may at some point reduce the need for facial reconstruction. “Minimally invasive surgery that does not require transcutaneous entry to get at the large defect areas may somewhat change the practice pattern,” he speculated.

Leave a Reply