© FERNANDO DA CUNHA / Science Source

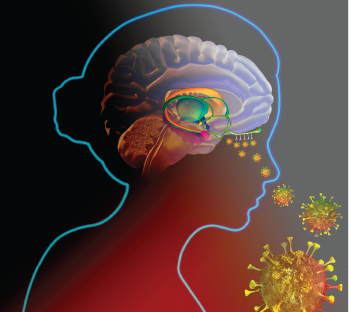

Anosmia has been widely acknowledged as a symptom of COVID-19. While olfactory dysfunction (OD) can be the first (and sometimes the only) symptom of COVID-19, some survivors still have not recovered their sense of smell nearly 18 months into the pandemic.

Explore This Issue

August 2021Many people, including physicians, may not be aware that olfactory distortions like parosmia, a distorted sense of smell, and phantosmia, olfactory hallucinations, are also associated with COVID-19. “They may mistakenly think this is something neurological or psychological,” said rhinologist Carol H. Yan, MD, an assistant professor at UC San Diego Health who specializes in rhinology and endoscopic skull base surgery. “But there are many COVID-19 patients who, unfortunately, experience this phenomenon.”

The exact reason for post-COVID-19 OD still isn’t completely understood, according to olfaction expert Jennifer Villwock, MD, an associate professor in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City. “It can be from viral-induced olfactory nerve damage, local inflammation and damage to the supporting cells and sinonasal epithelium, or both,” Dr. Villwock said. She added that approximately 90% to 96% of patients, depending on the study and timeline of follow-up, will experience at least some recovery of olfaction within 30 days of onset. Recovery rates tend to plateau after this time, with some studies reporting small gains in function out to 12 months.

For patients whose smell loss is longer lasting after COVID-19, doctors are starting to see a similar pattern to smell loss that occurs after other viruses. Eric Holbrook, MD, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and division chief of rhinology at Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston, said this type of anosmia can go on for months; some of his patients are having difficulty even after a year.

“With non-COVID-19 post-viral smell loss, the number of people who recover are estimated to be about 60% to 65%,” Dr. Holbrook said. He added that for patients with COVID-19-related smell loss, about 35% don’t recover in three weeks. “Extrapolating from past non-COVID-19 post-viral smell loss, we could probably predict that of the remaining 35% still having prolonged smell loss, maybe 60% or 70% will recover. We don’t know to what degree they will recover, however, because it’s still early in that assessment, and regeneration and recovery from damage to the olfactory epithelium can take quite a while.”

Olfactory dysfunction can be from viral-induced olfactory nerve damage, local inflammation and damage to the supporting cells and sinonasal epithelium, or both. —Jennifer Villwock, MD

Parosmia and Phantosmia

For those who do recover their sense of smell, the recovery isn’t always easy and can often be accompanied by parosmia and/or phantosmia. Both conditions have gained a lot of attention in connection with COVID-19, according to Bradley J. Goldstein, MD, PhD, an associate professor in the departments of head and neck surgery and communication sciences and of neurobiology at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, N.C.

“In a recent European study, parosmia was present in 28% to 59% of COVID-19 patients who had olfactory loss,” Dr. Goldstein said. While not everyone with smell loss will also develop parosmia, Dr. Goldstein added that it isn’t well understood why parosmia is so prominent in post-COVID-19 subjects and what exactly is causing it.

In COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 cases alike, parosmia and phantosmia often occur months after the initial illness or injury, Dr. Holbrook said. Phantosmia can occur during recovery from smell loss related to traumatic brain injury, for example, or can also be caused by seizures or migraines.

“As the regenerating nerves are finally making their way to connect into the olfactory bulb, which is the first brain structure that the nerves in the nose connect with, those nerves are not targeting back to the same spot that they did before,” Dr. Holbrook said. “So, the wiring is a little altered, and that alteration gives the experience of distorted smell.”

The distortion, unfortunately, does not lean toward scents like baking bread or fragrant roses. Common descriptors liken it to cigarette smoke, mold, rot, vomit, and sewage. And odors that may have previously smelled good to the patient, like coffee or their significant other, can trigger a really bad smell, which may cause a great deal more anxiety than smell loss alone. “For the patient, this isn’t promising, but since it can be a sign of recovery, a lot of us consider it a good thing,” said Dr. Holbrook.

For the patient, scent distortion isn’t promising, but since it can be a sign of recovery, a lot of us consider it a good thing. —Eric Holbrook, MD

Parosmia and phantosmia generally aren’t as well studied as anosmia or hyposmia, a loss of or a decreased sense of smell. This is also true in the setting of COVID-19. In Dr. Villwock’s practice, the majority of her patients who have survived COVID-19 will express some degree of parosmia and/or phantosmia and commonly describe it as “wet dog,” “moldy cigarette,” or some other “weird, bad smell.” It often seems unprovoked but can be triggered by exposure to an odorant, she said, and some have it constantly, while for others it’s intermittent.

“In my practice, patients are more likely to have these issues if they have some residual olfactory function,” Dr. Villwock said. “Prior to COVID-19, this was a phenomenon I was frequently seeing in my patients with persistent olfactory dysfunction from other viruses. Parosmia and/or phantosmia most commonly occurred during the first 12 months following the virus onset and usually lasted a few months before resolving itself.”

If patients visited her within that first year of smell loss, she would always counsel them about the possibility of developing parosmia and phantosmia. While she didn’t have a way to predict who would get it, she wanted them to be aware of the conditions so that they would not panic if either one developed.

Dr. Yan said that in her experience, parosmia typically occurs two to three months after COVID-19 patients have experienced their initial smell loss or had a COVID-19 diagnosis, and it seems to be more common in female patients. “Many people will say that they feel as though they’ve recovered somewhat in terms of their sense of smell,” she said, “and then a very sudden, abrupt light switch goes on and they realize their sense of smell has become completely distorted,” Dr. Yan said.

Ongoing Patient Impact

A sudden loss of or distortion of smell may not be as thoroughly life changing as a loss of or distortion of hearing or sight, but it can still be debilitating.

“Persistent olfactory dysfunction is very disturbing for those who experience it,” Dr. Villwock said. “It can have a significant negative impact on quality of life—especially related to nutrition and food enjoyment—and have significant safety implications in terms of hazard detection.”

As with other debilitating conditions, patients with COVID-19 related OD are taking solace in sharing information and experiences with each other. A Facebook COVID-19 Anosmia/Parosmia Support Group created in August 2020 now has more than 30,000 members, with more than 2,600 posts during the month of June 2021. Another group on Facebook called Parosmia/Phantosmia Support Group has more than 8,000 members.

Patients are notoriously bad at predicting their degree of smell loss. They often underpredict it or fail to recognize it. —Carol H. Yan, MD

Complicating OD, when patients have parosmia, they can also have dysgeusia, a distortion of taste that can make things taste sweet, bitter, sour, or metallic. This is often described as far worse than smell loss and can lead to significant dietary and nutrition concerns that can be traumatizing. “I had a patient who was unable to eat and had to be hospitalized with a feeding tube,” Dr. Yan said.

Smell Recovery Treatments

While there have been several studies published on treatments for post-viral smell loss, it’s too early to know which may specifically benefit COVID-19-related OD. There are some treatment options currently in use or in research:

Olfactory training. Although not specifically developed for COVID-19 smell loss, there is evidence that olfactory training can help patients with COVID-19-related OD. Typically, this consists of sniffing four different odors twice daily over at least 24 weeks (Olfactory Training. StatPearls Publishing. Updated 2020 December 24, 2020). “Olfactory training is a staple for any chemosensory or smell disorder, whether it’s smell loss, parosmia, or phantosmia,” Dr. Yan said.

Other therapies. When it comes to COVID-19 olfactory training, however, Dr. Yan combines it with other therapies. While she doesn’t recommend oral steroids due to the many possible side effects, she does prescribe budesonide, a topical steroid rinse that was shown to improve smell loss in a pre-COVID-19 randomized control trial, compared to just olfactory training and saline rinses alone (Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018;8:977-981). “The theory is that we are decreasing any localized inflammation that may be isolated to the olfactory cleft and not visible during endoscopy,” she said.

Other possible therapies under consideration include:

- Fish oil. Omega-3 fatty acids, with their anti-inflammatory properties, may offer another low-risk treatment for post-COVID-19-related OD. Several years ago, Zara M. Patel, MD, director of endoscopic skull base surgery at Stanford University, ran a randomized controlled trial using omega-3 in her endoscopic skull base surgery patient population (Neurosurgery. 2020;87:E91-E98). “In this patient group, almost a quarter of patients were having some form of long-term decrease in smelling ability,” she said. “With omega-3 supplementation, this dropped precipitously in comparison to the control group.” While Dr. Patel added that it would be an extrapolation to use this technique in post-viral smell loss cases, she does tell her patients that the risks associated with omega-3 are quite low and rare if they don’t have an underlying bleeding disorder or prostate cancer, and that there appears to be very little downside to taking it, even though it hasn’t been studied in their particular etiology of loss. (There may be hope for clinical data regarding omega-3 use soon: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of omega-3 and post-COVID-19 smell loss, led by Alfred-Marc Iloreta, MD, and David K. Lerner, MD, ended in June 2021 at Mount Sinai Hospital.)

- Theophylline. This known phosphodiesterase inhibitor, currently used to treat asthma, is being studied in a phase II, single-site, double-blinded, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial to determine its efficacy and safety for post-COVID-19 OD (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier). Theophylline has shown benefit in similar clinical trials for other forms of post-viral OD.

- Sodium citrate. Treatment using sodium citrate has been studied in both quantitative and qualitative OD, though not COVID-19-related OD. A paper published in January 2021 on a controlled trial of prolonged use of intranasal sodium citrate in quantitative and qualitative OD in 60 patients showed that there may be some benefit in treating phantosmia with the substance (Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278:2891-2897). The treatment, however, did not appear to improve smell loss in patients whose impairment was caused by infection. The study recommended further research to investigate this treatment’s effect on qualitative OD resulting from a variety of causes.

- Stem cell therapy. Dr. Goldstein, whose research includes studying the restoration of olfactory function in animal models using stem cell therapy, says this is a treatment that had shown some promise in animal models prior to COVID-19 (J Neurosci. 1996;16:4005-16; Chem Senses. 2020;45:493-502). “We used a tissue-specific purified rodent olfactory epithelial basal stem cell—a bona fide olfactory neuronal progenitor—in those studies,” he said. “There are a lot of barriers to translating this to humans that would require more research.”

- Platelet-rich plasma. Before the pandemic, Dr. Patel took an interest in platelet-rich plasma (PRP) because of its burgeoning use in other medical specialties. “It was being used in aesthetic clinics for facial rejuvenation and hair growth, but also in orthopedic clinics for joint cartilage regeneration and in neurology for nerve regeneration,” she said. “This last use caught my interest because that’s really what we want to do with the olfactory system when it’s damaged—we want to harness its inherent regenerative capability and stimulate it to function again.” Dr. Patel did a pilot study in which Dr. Yan was involved as a fellow, looking at PRP injections into the olfactory cleft (Laryngoscope. 2020;5:187-193). “We only enrolled low numbers at that time to confirm the safety of the injections—I wanted to make sure I wouldn’t make anyone worse or cause tumor growth—and we did prove safety,” Dr. Patel said. Without a placebo arm, efficacy wasn’t something the study could conclude, but researchers did see interesting improvement in patients’ threshold for smell, enough for Dr. Patel to want to conduct the randomized, controlled trial that she is currently running (at press time, due to be completed in July 2021). Dr. Yan has gotten UCSD up and running as a second site. “I’m excited we’ll be able to enroll patients more quickly and get to our answer faster as to whether this treatment option is really going to be beneficial for these patients,” Dr. Patel said.

Dr. Holbrook cautions, however, that mixing olfactory training with other therapies makes it challenging to know what’s working and what isn’t. “Even without olfactory training, the body is able to heal and recover and can regenerate new nerves,” Dr. Holbrook said. “In addition, smell recovery can be difficult to study because there’s already an underlying improvement that can occur.”

Another challenge in healing post-COVID-19 OD is that some patients don’t realize that they’re having problems. “Patients are notoriously bad at predicting their degree of smell loss. They often underpredict it or fail to recognize it,” said Dr. Yan. “Basically, there’s a discrepancy between subjective, patient-reported smell loss and objective testing.”

Dr. Villwock cited a recent study conducted over the course of one year in patients with post-COVID-19 OD that found a discrepancy between self-assessed and objective sense of smell. “The study noted that this could be due to issues inherent to either self-assessment strategies or a limited ability of the utilized olfactory tests to completely capture subtle differences in olfactory performance that are meaningful in the context of daily life,” she said.

Overall, however, the gentlest option may be to allow the body to heal itself, even if this might be the slowest alternative. “Although there are various treatments, one option is to just give it time,” Dr. Yan said.

Renée Bacher is a freelance medical writer based in Louisiana

Olfactory Registries and Reporting Tools

As new studies and therapeutics emerge to better understand and treat olfactory disorders, olfactory registries can help patients. Jennifer Villwock, MD, said her team at the University of Kansas maintains an olfactory registry, and she reassures her patients that she will be in touch as new clinical trials emerge. “Referrals to sites actively engaging in this work may be helpful,” she said.

The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery has also created an anonymous reporting tool to help establish the importance of anosmia and dysgeusia in the diagnosis and progression of COVID-19, and to allow healthcare providers of all specialties and patients worldwide to submit data confidentially (visit https://www.entnet.org/covid-19-anosmia-reporting-tool/).

TikTok Treatments?

Treatments for post-COVID-19 olfactory disorder abound on social media.

One particular idea making its way around the social media site TikTok involves placing a finger on the forehead while another person flicks the back of the person’s head. (TikTok Users Are Flicking Each Other in the Head to Regain Taste and Smell After COVID-19 — But Does It Work? Shape. March 2, 2021.). The technique can be traced back to a YouTube video, posted by the news outlet AZ Family, in which a chiropractor advocates a second move to stimulate the olfactory nerve: sticking out the tongue and touching a finger to the tip while being flicked on the back of the head.

Eric Holbrook, MD, calls these treatments not only bogus but potentially dangerous. “Patients need to understand that social media is not a proper resource for medical advice and that they should speak with a physician,” he said. “We as physicians also need to educate these patients and be careful about what we suggest—we need to be careful about what we publish in the literature to avoid suggesting therapies that aren’t proven effective, and we need to carefully read published articles to make sure they have proper studies to back up any claim of real benefit.”