During the last 50 years, the debate over the merits of canal-wall-up (CWU) versus canal-wall-down (CWD) surgery for removing pediatric cholesteatomas has shifted focus several times.

The traditional pro/con arguments are familiar to most otolaryngologists. The major advantage of the CWU procedure is that it preserves the canal wall and other key structures of the middle ear. That preservation enables patients to get the ear wet and eliminates the need for repeated cleaning of the large surgical cavity left behind by the more invasive CWD approach. Hearing results are also purported to be better in CWU-treated patients, although studies are split on whether that is truly a distinguishing factor.

The major downside to the CWU approach is a high rate of recurrent disease, ranging up to 50 percent in some studies and clinical experience. The recurrences often occur because it is difficult to see the entire middle ear and epitympanum when the canal wall is left intact during surgery. As a result, disease is left behind and can recur six to 12 months later.

Historically, for most otolaryngologists, adopting either the CWD or CWU approach has hinged on the amount of weight they placed on these risks and benefits. More recently, however, a new argument has been injected into the debate: whether newer, hybrid approaches that combine the best aspects of CWU and CWD surgery should become the standard of care for treating pediatric cholesteatomas.

Surgeons, Take Your Corners

Bruce Gantz, MD, FACS, professor and head of the University of Iowa Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery in Iowa City, is one of several leading otolaryngologists who have adopted a hybrid approach. His technique, tympanomastoidectomy followed by canal wall reconstruction and mastoid obliteration, is detailed in the Iowa Head and Neck Protocols (http://wiki.uiowa.edu/display/protocols).

Dr. Gantz said that about 90 percent of the patients in his practice can be managed with canal wall reconstruction. During the procedure, the canal wall is taken down with a microsaw, Dr. Gantz explained. This technique provides a view similar to a canal-wall-down exposure and allows the best possible view for total cholesteatoma removal. The ear is then reconstructed by putting the canal wall back in, blocking the attic with a bone graft from the mastoid tip and obliterating the mastoid with bone pâté. “It isolates the attic and mastoid from the tympanum, which prevents recurrent retraction of the tympanic membrane, a major cause of recurrent disease in children with poorly functioning Eustachian tubes,” he explained. A second-look surgery is done six to eight months later to assess results and complete aspects of the reconstruction.

“Almost all of our ears are dry, without recurrent retraction pockets, so patients can swim and bathe with no problem,” Dr. Gantz said. “With CWD, in contrast, you have a wet ear, and patients are going to need repeat visits back to the surgeon for debridement and drainage, sometimes requiring sedation.” As for hearing results, “they’re mixed,” he noted, due to compromised Eustachian tube function.

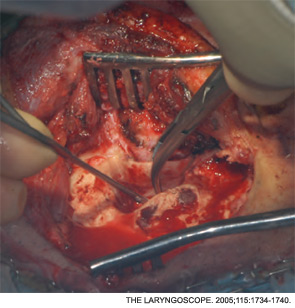

Of 130 cases studied by Dr. Gantz and colleagues in 2005, the failure rate of the canal wall reconstruction technique was 1.2 percent (Laryngoscope. 2005;115(10):1734-1740). “By failure, we mean patients who had recurrent cholesteatomas and required a repeat surgery, in which case we do a traditional CWD procedure but try to use periosteal flaps and muscle flaps,” he said.

Given that low failure rate, is canal wall reconstruction and mastoid obliteration a technique that more surgeons should be offering patients with cholesteatomas? “I guess it depends on how you’ve been trained,” Dr. Gantz said. “The surgeons who have been trained at [the University of Iowa] understand this, and many of my fellows and residents still do it in their own practices. It does take some time to learn and requires some finesse to do well, and it’s certainly more complicated than a traditional canal-wall-up.”

He added that some physicians are hesitant to adopt the canal wall reconstruction technique because the facial nerve is thought to be at risk during the procedure. “But I haven’t had any instances where we injured the nerve,” Dr. Gantz said.

He urged surgeons to consider another benefit of his approach: “You don’t have to wait until you’re actually operating on the patient to decide whether to take the canal wall down or leave it up,” he said. “I always found that type of intraoperative planning [with traditional CWD or CWU] very unsatisfactory; you’re not always a good judge of the disease process at that point.”

After seeing way too many patients who needed repeated surgeries after leaving the canal wall up, I knew there had to be a better way.

After seeing way too many patients who needed repeated surgeries after leaving the canal wall up, I knew there had to be a better way.—John L. Dornhoffer, MD

Canal-Wall-Up Defended

According to John P. Leonetti, MD, director of the Center for Cranial Base Surgery at Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine, both CWU and CWD procedures have roles in the management of cholesteatomas. Unlike Dr. Gantz, he prefers to decide intraoperatively which of the two procedures is needed.

“If I determine that the cholesteatoma involves the mastoid air cells to the degree that I am not confident I can remove every skin cell in the mastoid cavity, then I’ll do a [CWD] mastoidectomy,” he said. “In children, I try to make that surgical cavity and the meatus as small as possible, so it’s less conspicuous.” As a result, Dr. Leonetti noted, about 90 percent of the patients he treats with CWD surgery can get the ear wet after three months.

Dr. Leonetti typically plans a second look procedure about six to nine months post surgery. The benefits of such an approach are two-fold, he said: During the second-look surgery, “you can make sure the cholesteatoma has not recurred, and you also have a pristine environment in which to reconstruct the hearing.”

In 2006, Dr. Leonetti co-authored a review of 16 years of his experience treating pediatric cholesteatomas (Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1603-1607). The review included 106 mastoidectomies (86 acquired, 20 congenital) performed in children 16 years old and younger from 1988 to 2003. Follow-up ranged from two to 12 years, with a mean of six years.

Rates of recurrent cholesteatomas were similar in CWU and CWD patients (8 percent and 6 percent, respectively). “Good serviceable hearing,” as measured by the percent of patients with a pure-tone average greater than 25 dB, was higher in the CWU group than the CWD group (81 percent vs. 47 percent, respectively.) The researchers concluded that the CWU procedure “is an adequate surgical option for treating most acquired and congenital cholesteatomas, preventing disease recurrence and maintaining good hearing outcomes.”

Asked whether those findings hold true today, Dr. Leonetti replied, “Absolutely. We still get only about a five percent rate of patients needing repeat procedures for recurrent disease, beyond the second-look operation. And our hearing results continue to be good.”

Why do other surgeons and some published studies cite much higher rates of recurrence in children treated with CWU surgery? “I can’t really say. But one question I would ask is, ‘How much ear surgery are you doing?’ The skill, training and experience of the surgeon will all impact the final treatment outcome,” Dr. Leonetti said.

Retrograde Technique

John L. Dornhoffer, MD, director of otology/neurotology at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, took issue with the idea that the high recurrence rates often associated with CWU surgery are surgeon-dependent to some degree.

“I’m a very experienced otologic surgeon. I’ve been trained by some of the top people in the field, and I’ve done hundreds of canal-wall-ups,” Dr. Dornhoffer said. “After seeing way too many patients who needed repeated surgeries after leaving the canal wall up, I knew there had to be a better way.”

Dr. Dornhoffer eventually adopted a hybrid technique in which the upper canal wall is taken down temporarily to gain maximum exposure in the epitympanum, the cholesteatoma is removed in a retrograde approach for better visualization, and the canal defect is reconstructed using autologous cartilage from the cymba area of the conchal bowl.

In 2004, Dr. Dornhoffer published a review of his eight-year experience with the technique (Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:653-660). The review included 46 patients, representing 50 ears (20 pediatric, 30 adult), who had undergone cholesteatoma surgery using the retrograde technique. The recurrence rate was 16 percent for all patients, including smokers, “which really is superior to most reviews of traditional CWU surgery, where long-term recurrence rates can be well over 50 percent,” Dr. Dornhoffer said.

Since that study was done, he added, “I have done about a thousand ears using the retrograde technique, and I would say our rate of recurrence is down to about 10 percent using a single-stage surgery in more than 90 percent of patients.”

Dr. Dornhoffer acknowledged that his technique, which he learned from a prominent ENT surgeon in Germany, is not well accepted by otorhinolaryngologists in the U.S. “The retrograde approach is very different,” he said. “It takes some getting used to because it is really a hybrid between the traditional techniques of canal wall down and canal wall up.”

But he stressed that such reluctance should not detract from the larger point of his evolving experience with removing cholesteatomas in children. “The current thinking on canal-wall-up surgery, where surgeons knowingly commit patients to at least an initial surgery followed by a planned second-look surgery, is really not acceptable in this era of cost containment,” he said.

Dr. Gantz echoed Dr. Dornhoffer’s concerns over the economics of cholesteatoma surgery. “How many times are insurance companies going to pay for failure?” he said. “I would not be surprised if, someday, third-party payers tell you that they do not want you to continue with techniques that require several operations, especially where you have [such a significant] failure rate.”

With his mastoid reconstruction technique, for example, “you basically get rid of everything that predisposes patients to recurrent cholesteatomas, such as the mastoid mucosa. Yes, you have to be a very meticulous surgeon to do all of that, and to be sure you’re not trapping cholesteatoma-prone skin in the area of reconstruction. But it’s a learnable technique and one that truly benefits a large range of children and adult patients.”

When to Convert?

Jeffrey P. Harris, MD, PhD, FACS, professor and chief of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at the University of California, San Diego, said that he also has seen a high rate of recurrences with CWU. But he has not abandoned the procedure completely. He still does CWU surgery in most patients with new cholesteatomas, but now he is much more willing to take the canal wall down if, at a planned second-look surgery, disease recurs. That willingness “is mostly due to the nature of this disease in children,” Dr. Harris explained. “Most of them have very poor Eustachian tube function. As a result, negative pressure builds up in the middle ear, and when the canal wall is left intact, that pressure pulls tissue into the epitympanum space where cholesteatomas often reform.”

Dr. Harris said that after many years of doing CWU surgery, he realized that about 40 percent of his patients showed signs of having recurrent cholesteatomas at the time of their second-look procedures. Those lesions, he stressed, “were not recurrent disease based on my leaving some of the cholesteatoma behind; this was what we call ‘recidivistic’ disease, a new cholesteatoma, because the ear, especially in kids, simply could not maintain normal middle ear pressure. Once that negative pressure develops, the eardrum gets sucked in, and when it does, that’s my clue to take the canal wall down and stop the disease process.”

If negative pressure is observed during the healing phase, Dr. Harris added, “it is worth placing a ventilation tube in the ear, because on occasion the tube can prevent recurrence of these epitympanic retractions.”

A Historical Reversal

Dr. Harris said there is nothing unique about his negative experiences with traditional CWU surgery. He pointed to Gordon Smyth, MD, from Belfast, who was initially a staunch advocate of leaving the canal wall intact. Dr. Harris noted that Dr. Smyth was influenced, as were many other surgeons of the day, by the House Clinic’s James L. Sheehy, MD, an ENT surgeon at the House Clinic in Los Angeles, who championed the CWU approach in the 1970s and 1980s. “Dr. Smyth performed canal wall ups in most of his patients for at least five years, maybe longer,” he said. “Then he reviewed his long-term results and wrote a paper in which he stated that this operation resulted in a much higher than acceptable recurrence rate for cholesteatoma; he was seeing up to 50 percent of his patients having to go back for more surgery” (Laryngoscope. 1985;95(1):92-96).

Based on those types of experiences, “most surgeons would agree that the holy grail of maintaining a canal-wall-up approach, no matter what, to all comers, really makes no sense today,” Dr. Harris said. “The pendulum has swung back to what had been the gold standard: canal wall down.”

Leave a Reply